It Took 60,000 Years to Kill Nearly Everything on Earth

It took only 60,000 years to kill more than 90 percent of all life on Earth, according to the most precise study yet of the Permian mass extinction, the greatest die-off in the past 540 million years.

The new timeline doesn't reveal the culprit behind the die-off, though scientists have several suspects, such as volcanic eruptions in Siberia that belched massive quantities of climate-changing gases. But pinning down the duration of the Permian mass extinction will help researchers refine its potential trigger mechanisms, said Seth Burgess, lead study author and a geochemist at MIT.

"Whatever caused the extinction was really rapid, or the biosphere reached some critical threshold," Burgess told Live Science. "Having an accurate timeline for the events surrounding the mass extinction and the interval itself is extremely important, because it gives us an idea of how the biosphere responds."

The findings were published today (Feb. 10) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Radioactivity and extinctions

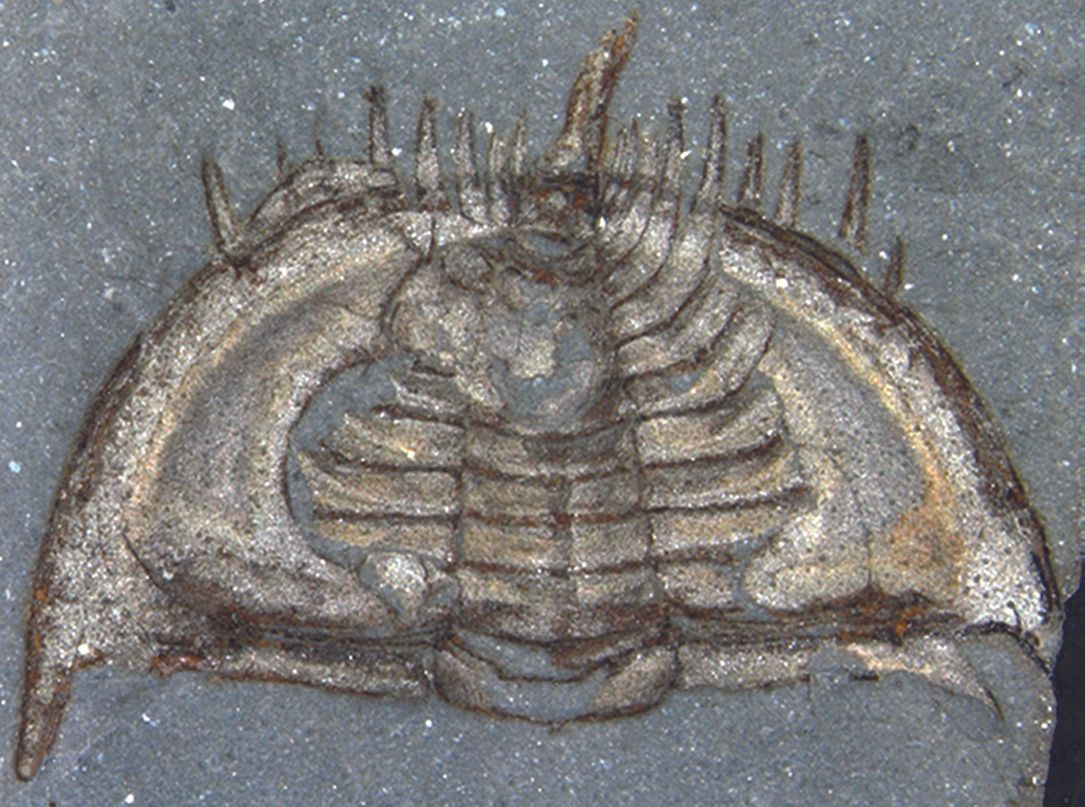

The Permian mass extinction marks the end of the Permian geologic period, which ended approximately 252 million years ago. More than 96 percent of marine life and 70 percent of land species perished. By comparison, 85 percent of life died off during the dinosaur-killing extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period, 66 million years ago. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

"This is one of the fundamental inflection points in the trajectory of life on Earth," Burgess said. "It set the stage for the [rest] of evolution."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The best record of the Permian "great dying" is in Meishan, China. In past decades, hundreds of geologists collected and analyzed rocks in Meishan that date from before, during and after the Permian extinction. Researchers analyzed these rocks to better understand what caused the Permian event. Volcanic ash beds interlaced with Meishan marine rocks have tiny minerals called zircons that can be precisely dated with geochemical techniques, and the marine rocks carry scores of fossils that record the die-off and resurgence of life.

Burgess and his co-authors improved the Meishan rock ages with the latest high-resolution, uranium-lead zircon dating techniques. Zircon traps minute amounts of naturally occurring radioactive uranium inside its crystal structure. Uranium decays into lead, and counting the ratio of the two elements provides an age estimate for the zircons.

The new dates show that the mass extinction started 251.941 million years ago (plus or minus 37,000 years) and ended at 251.880 million years ago (plus or minus 31,000 thousand years). The extinction's end also marks the start of the Triassic period, and coincides with the first fossil appearance at Meishan of a toothy, eel-like creature called Hindeodus parvus (a conodont, the source of the earliest teeth found in the fossil record).

Finding the killer(s)

The new timeline also provides greater accuracy for the environmental blows linked with the mass dying. For example, previous work has found an increase in carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, before the mass extinction began. In the Permian rocks, atmospheric carbon dioxide shifts are recorded as changes in the ratio of carbon isotopes.

The new study suggests the increase in carbon dioxide was sudden and short-lived, Burgess said. "It precedes the extinction by 20,000 years or so, and lasts 10,000 or 15,000 years. It was very short-duration event," he said.

But there are other potential tipping points for extinction beyond atmospheric greenhouse gases. For example, sea surface temperatures also rose about 18 degrees Fahrenheit (10 degrees Celsius) over a period beginning before the extinction and continuing into the early Triassic. And the sudden carbon dioxide increase may have made the oceans more acidic. (A similar effect is happening in the present age due to carbon dioxide concentrations that have been rising because of man-made sources since the 1850s.) [Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth]

"An accurate and high-precision age model gives us a reliable sounding [board] against which we can start comparing all of the other things that started happening with the mass extinction," Burgess said.

The research team is now applying the same age-dating technique to one of the main Permian mass extinction suspects, volcanic rocks from the Siberian Traps, one of the largest volcanic outpourings on Earth.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.