Why Is It So Hard To Forecast Winter Storms?

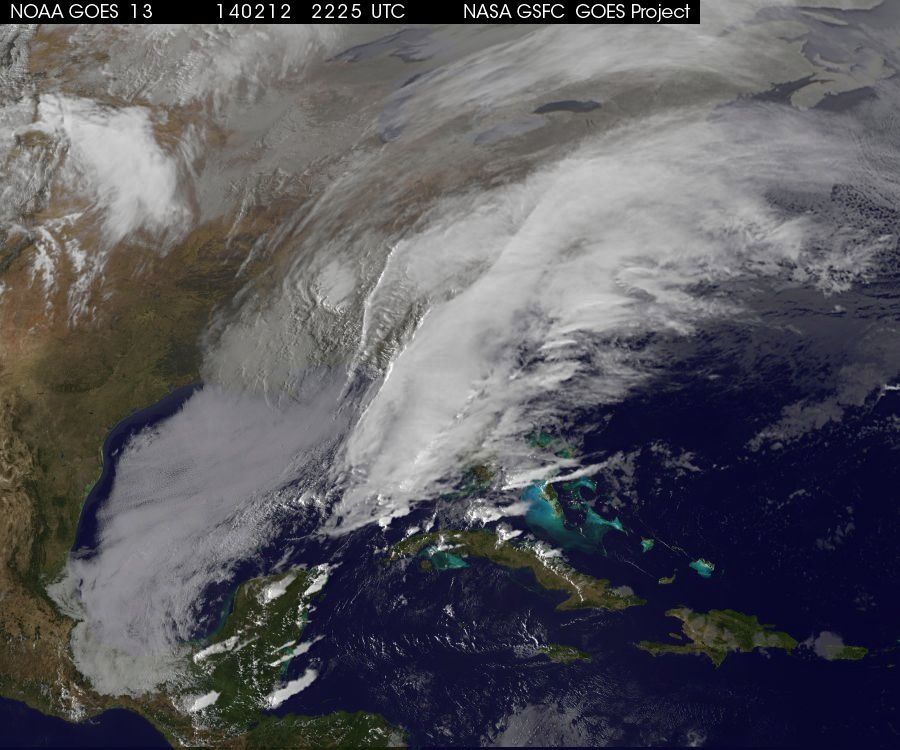

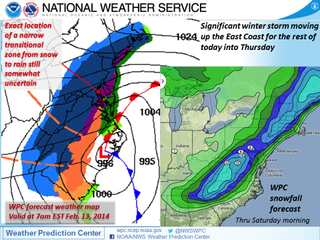

A winter storm is barreling across the southeastern United States today (Feb. 12), lashing parts of Georgia and the Carolinas with ice and snow. The frosty system is expected to make its way north over the next 24 hours, and forecasters say it could dump a mix of sleet and snow in a broad swath of the East Coast up to Maine. But, narrowing down what type of wintry precipitation will fall and exactly where can be challenging, experts say.

"It's easier to forecast if precipitation is going to fall, in general, but the hard part is figuring out what form it's going to be," said Eli Jacks, chief of fire and public weather services at the National Weather Service (NWS) in Silver Spring, Md. "A lot of the challenge in forecasting this storm is whether it will stay all snow, or if it will be freezing rain and sleet mixed in."

In the South, the NWS has cautioned that the ice storm could have "potentially catastrophic" and "crippling" effects, and the agency said more than an inch of ice could accumulate from central Georgia into South Carolina through Thursday morning (Feb. 13). [See a time-lapse video of the massive winter storm]

A state of emergency is currently in effect in Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and in more than 80 counties in Georgia. Thousands of flights across the region have been grounded, and more than 200,000 homes and businesses in Atlanta were without power early Wednesday, reported NBC News.

Wintry mix

The storm is expected to intensify and begin its northeastward crawl over the next couple days. Snowfall totals will increase from the coasts moving inland, according to the NWS, with some places of interior New York, New Hampshire and Maine potentially getting more than 2 feet (0.6 meter) of snow. New York City could see 10 to 14 inches of snow, Philadelphia 8 to 10 inches and Washington, D.C., 5 to 10 inches.

But that's not all. Communities along the storm's path could also be pelted by sleet and freezing rain, and trying to figure out which areas will be impacted by different types of precipitation can be tricky. This is because forecasters need to understand the vertical structure of temperatures in the atmosphere — from high up in the atmosphere all the way down to surface temperatures — in order to figure out what type of precipitation will fall, and how much, Jacks told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"With ice, it's very warm in the atmosphere except very near the ground," he explained. "Precipitation falls as rain but then hits the cold layer and freezes on contact. With a thicker layer of cold air, it still falls as rain but then partially freezes on the way down and hits the ground as sleet."

When it snows, precipitation falls through cold air and stays frozen the entire time. But without knowing the vertical structure of temperatures in the atmosphere, it can be challenging to forecast whether the precipitation will remain as snow, or will be mixed with freezing rain and sleet.

Even when meteorologists make snowfall predictions, however, the numbers can seem imprecise. This is because there can be variability in how much snow falls, based on the moisture content in the atmosphere.

Weather experts use a measure called liquid equivalent precipitation to figure out the ratio of projected snow to inches of rain (for instance, a 10:1 ratio means 10 inches of snow could fall from an inch of rain). But, wetter conditions can skew the ratio, Jacks said. [The 10 Worst Blizzards in US History]

"If it's wetter, things are more compact, and that same inch of rain might create 15 inches of snow, or more than that. Our models do a pretty good job of predicting this, but they're certainly not perfect."

Predicting the weather

James Marshall Shepherd, director of the Program in Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Georgia in Athens, and the 2013 president of the American Meteorological Society, said this week's storm was well-predicted by weather models.

"With southern storms, the timing of the moisture and the placement of cold air can be tricky, but in this case seemed to be handled pretty well for us here," Shepherd told Live Science in an email.

For this type of winter system, meteorologists can typically see it forming about a week before it hits, Jacks said, but many of the preliminary models will eventually change as the storm approaches.

"Our confidence levels start going up three days before, and we can usually be more precise about where the rain and snow lines may be," he explained.

Yesterday, the NWS flew one of the U.S. Air Force's sensor-laden Hurricane Hunter aircrafts over the Gulf of Mexico to collect atmospheric data. As their name suggests, these planes are typically used to probe and gather readings about the path and intensity of a storm or hurricane. Yesterday's mission was used to further refine the NWS' weather models.

"The accuracy of our models is determined, in part, by the quality of the information that goes into them," Jacks said. "The first thing we want to do is incorporate lots of data from land observations and upper air observations. The more information we can put into these models, the better the predictions will be, and that makes all the difference when that information reaches people."

Still, making predictions about the weather is challenging, and despite gains in technology, there will always be a level of unpredictability, Jacks said.

"The atmosphere is very random, and there are lots of things that interact — water, the structure of the atmosphere, friction from the land," he said. "To me, it's quite amazing that we can capture it at all."

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.