EPA Vastly Misjudges Methane Leaks, Study Confirms

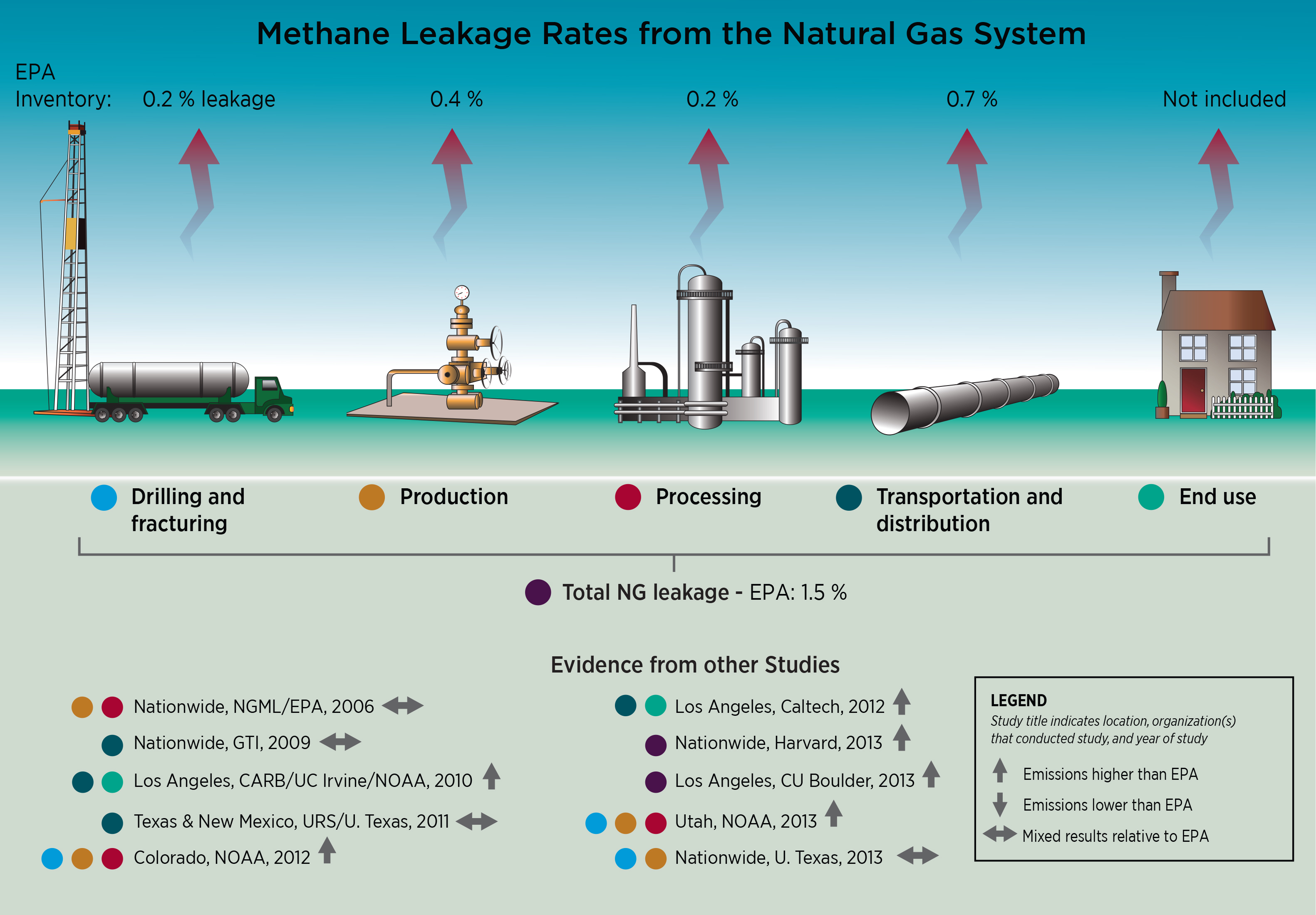

The federal government has underestimated methane emissions from the United States by 50 percent for the past 20 years, according to a comprehensive new study.

Methane, also called natural gas, is a powerful but short-lived greenhouse gas. It lasts just nine years in Earth's atmosphere but is about 34 times more potent at trapping infrared radiation (the greenhouse effect) than carbon dioxide, which is more abundant and lasts longer. While methane spews into the sky from both natural sources, such as wetlands, and human activities, including oil and gas production, the government estimates only track manmade sources.

The review of scientific studies of methane emissions suggests that Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) methane counts are about 50 percent too low, though the underestimate could range from 25 percent to as much as 75 percent. That means the United States is pumping about 14 million tons more methane than thought into the atmosphere each year, according to the findings, published today (Feb. 13) in the journal Science.

"Evidence from numerous studies consistently suggest that methane emissions are larger than those estimated by the EPA inventory," said Adam Brandt, lead study author and an energy resources engineer at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif.

The review analyzed the results of more than 200 studies that traced methane emissions across the United States and were published in the past 20 years. The results were compared to the EPA's Greenhouse Gas Inventory, which records methane emissions and other climate-changing gases.

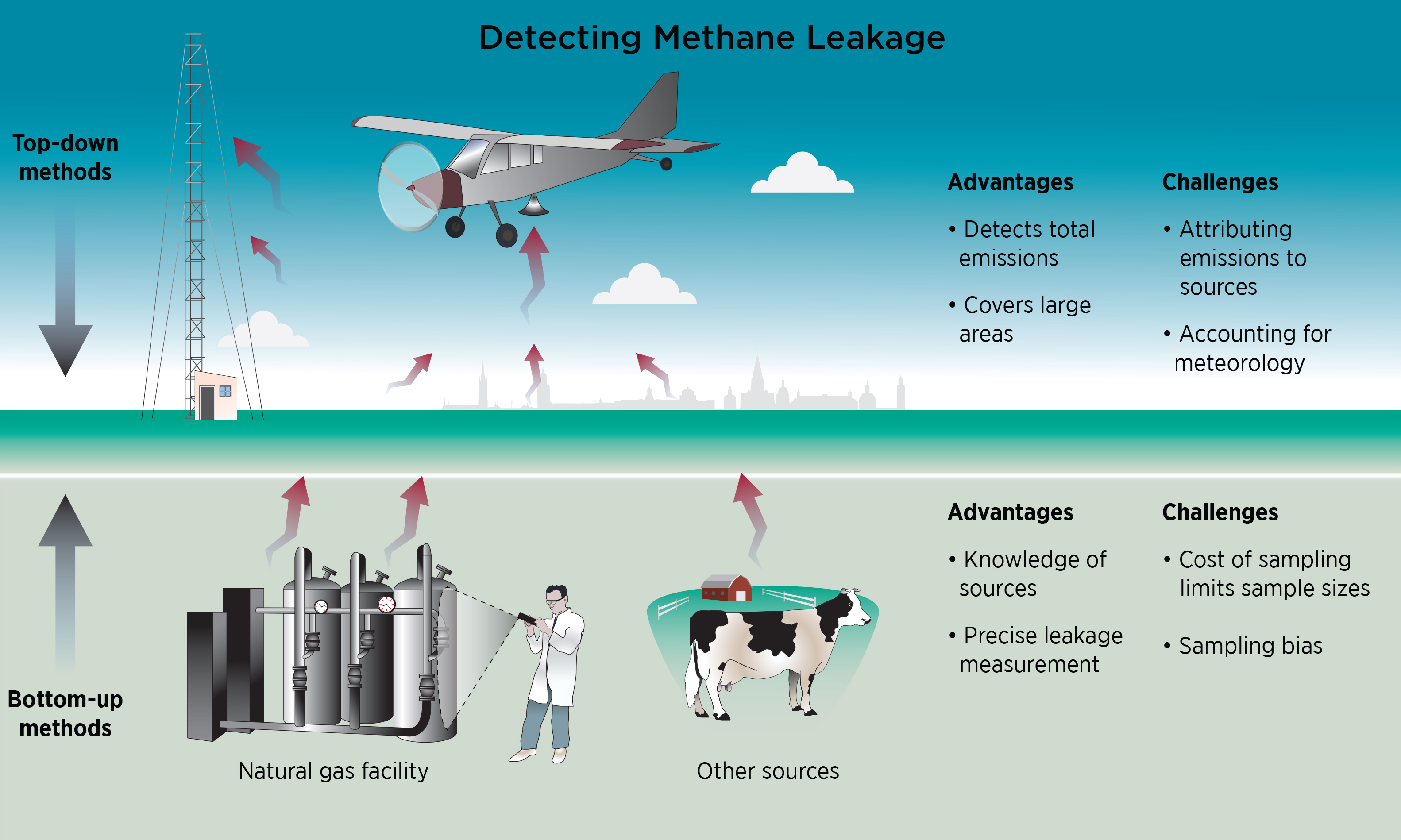

This isn't the first time a serious discrepancy has shown up between official methane estimates and a scientific study. For example, the EPA's "bottom-up" approach, which measures natural gas outputs directly from the source, can come up with vastly different figures than "top-down" studies, which measure air-borne gas concentrations. A study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in November 2013 using the top-down approach also found a 50 percent underestimate.

"There have been a lot of studies that … superficially, have seemingly contradictory results," Brandt said. "Really, they were performed at different scales with different methodologies."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new study sought to synthesize the results of both approaches, and provide a better estimate of natural gas emissions across the United States. It was funded by Novim, a nonprofit group aimed at providing scientific data on major world problems, through a grant from the Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation.

Natural gas as fuel

One of the biggest U.S. methane emitters is the natural gas industry. Leaks come from drilling for oil and gas, refining plants and transport and distribution, such as pipelines.

The study finds that just a small number of super-emitters in the natural gas industry are likely responsible for more than half of the industry's methane leaks. Finding these super-emitters, which account for less than 1 percent of all leaking devices, is a challenge for industry, Brandt said. "There's about a half a million wells and a couple million miles of pipeline, so it's a very big and very complex system," he said. "But if they know where the leak is they want to fix it, because it's costing them money." Greenhouse Gases: The Biggest Emitters (Infographic)

Cleaning up leaks would finally make natural gas cleaner than diesel, the study finds. Currently, the leaks in the gas system mean that running trucks and buses on diesel is still cleaner than natural gas, the researchers said.

But even though the natural gas system is sloppier than the EPA estimates, it's still cleaner than coal, the study concludes. Switching to coal-fired power plants over natural gas would produce more climate warming, even if the natural gas system was responsible for all of the U.S. methane leaks reported in the study, the researchers said.

In response to concerns about natural gas extraction leakage, the EPA is considering tightening federal regulations on oil and gas drilling to reduce methane emissions.

An agency spokesperson said the study results have not been reviewed yet. "EPA is aware of methane studies that result in estimates of national methane emissions that differ from EPA's estimates, and is interested in feedback on how information from such studies can be used to improve U.S. GHG [greenhouse gas] Inventory estimates," the agency said in a statement.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.