Termite-Inspired Robots Could Be Future Construction Workers

Imagine a fleet of robotic construction workers that can autonomously build structures and work together harmoniously without needing supervision or specific, pre-determined roles.

Researchers at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, both in Cambridge, Mass., are designing just this sort of robotic construction crew.

The engineers were inspired by the way millions of termites cooperate to build complex mounds of soil hundreds of times their size without needing detailed blueprints for the structures. Instead, the colony members use cues from each other and their environment to guide the construction process, the researchers said. [Video: Termite-Bots: Construction Technology Revolution?]

"We learned the incredible things these tiny insects can build and said: 'Fantastic. Now how do we create and program robots that work in similar ways but build what humans want?'" study lead author Justin Werfel, a researcher at the Wyss Institute, said in a statement.

Human construction crews typically operate in a hierarchical system, with a foreman managing trained workers to carry out a detailed plan.

"In insect colonies, it's not as if the queen is giving them all individual instructions," Werfel said. "Each termite doesn't know what the others are doing or what the current overall state of the mound is."

Teamwork pays off

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

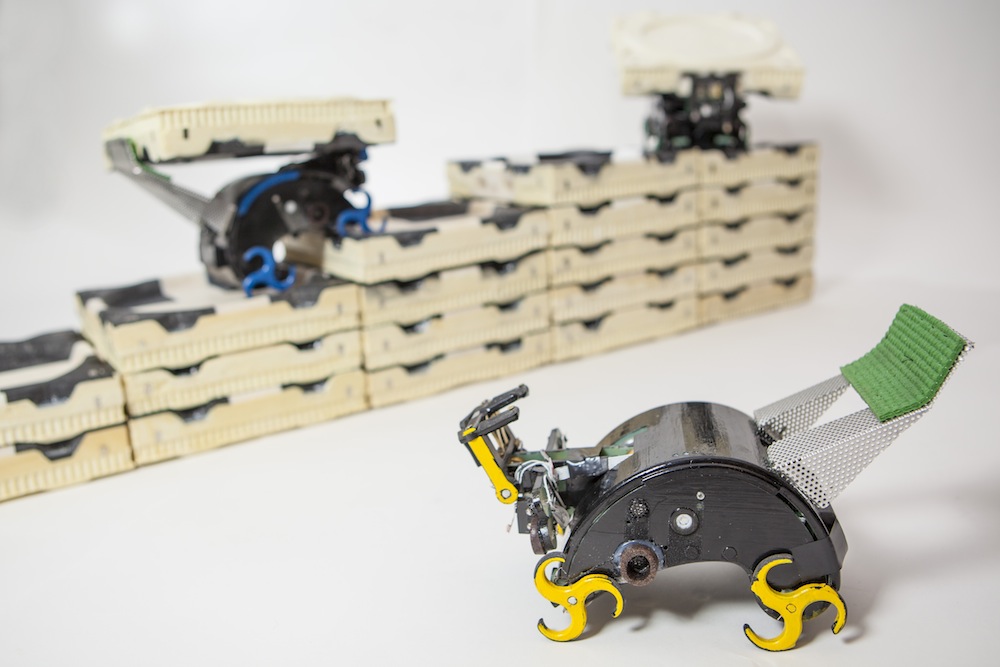

The researchers spent four years developing a team of small robots, called TERMES, that can autonomously build complicated, three-dimensional structures — towers, castles and pyramids, for instance — out of foam bricks. Each robot carries out part of the building process in parallel with its teammates, but none of the workers have a prescribed role, which means if one of the robots breaks or has to leave, progress on the overall structure is not impacted.

Each robot is equipped with sensors to detect the presence of a brick or another robot in its path. If the robot senses a brick, it can lift and deposit the cargo to the next open spot at the construction site.

The robots are programmed to move along a grid, and they follow "traffic laws" that dictate where they move around and place bricks, based on the specific structure.

"Traffic can only flow in one direction between any two adjacent sites, which keeps a flow of robots and material moving through the structure," Werfel said. "The safety checks involve a robot looking at the sites immediately around itself, paying attention to where the bricks already are and where others are supposed to be, and making sure certain conditions in that local area are satisfied."

This type of collective intelligence also means the same instructions can be carried out by a small team of five robots, or a much larger crew of 500, the researchers said. In the future, similar robotic systems could be used for construction projects deemed too dangerous for humans, or for simple construction tasks on Mars, the researchers said.

"While that's likely a long way out, a shorter-term application could be something like building levees out of sandbags for flood protection," Werfel said.

The robotic system could also be adapted to include a central controller, should that be necessary, the researchers said. For instance, if the robots are working in a dangerous or remote environment, it may be preferable for a human supervisor overseeing the progress and efficiency of the robotic construction crew.

"It may be that in the end you want something in between the centralized and the decentralized system —but we've proven the extreme end of the scale: that it could be just like the termites," principal investigator Radhika Nagpal, a professor of computer science at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, said in a statement. "And from the termites' point of view, it's working out great."

The research was detailed in a study published online today (Feb. 13) in the journal Science.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.