Scientists can now visualize genes whose activity gets shut off in single cells.

The new technique, which will be described today (Feb. 18) at the 58th annual meeting of the Biophysical Society in San Francisco, helps visualize the process behind calico cats' patchy, multi-colored fur. Scientists could one day use the method to untangle the mysteries behind certain sex-linked genetic diseases, researchers say.

Patchy problem

Cells carry genetic information on chromosomes, the threadlike structures made of DNA and proteins that code for hereditary traits such as eye color and height. Humans have 22 pairs of regular chromosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes. Under a microscope, the sex chromosomes look somewhat like an X or a Y in shape just before cell division. (Most of the time, all chromosomes just look like amorphous blobs with complicated shapes ) [7 Diseases You Could Learn About from a Genetic Test]

Females inherit two copies of the X sex chromosome, one from each parent, whereas males get an X chromosome from their mothers and a Y chromosome from their fathers. Practically speaking, that means each female has two times the X genes she needs, which could theoretically create a toxic "overload" of the proteins made by those genes, said study co-author Gerard McDermott, a research biophysicist at the University of California, San Francisco. Called the "workhorses of genes," proteins perform many of the functions in the body.

"So in every female cell, one of the X chromosomes just gets shut down," in a mysterious process that seems to be somewhat random, McDermott told Live Science.

Since the 1960s, scientists have known that such X-chromosome inactivation took place, and was responsible for the varied, splotchy coats of calico cats. That's because the gene for fur color is located on the X chromosome, and each cell in a calico kitty's body has one X chromosome shut off in a somewhat random manner.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Real-time visualization

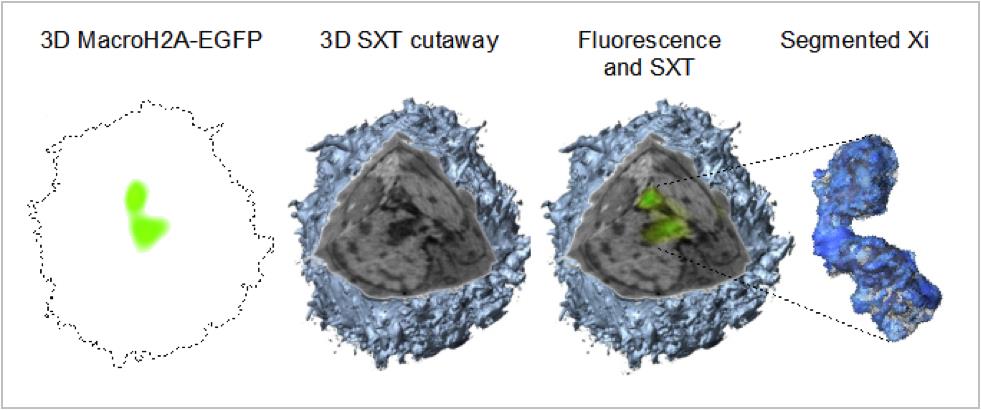

But finding ways to visualize this gene inactivation precisely in individual cells was trickier. To do so, McDermott and his colleagues combined two imaging techniques.

One, called soft X-ray tomography, captures whole cells in three dimensions. The other technique, called cryogenic fluorescence tomography, uses fluorescent tags to reveal where individual molecules are located inside the cells. That can, therefore, reveal whether certain genes are active or silenced.

Doctors could one day use the new method to study X-linked genetic diseases, McDermott said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.