San Francisco's Deadly 1906 Earthquake Was Last of Three

California's rock-and-roll reputation was set more than a century ago, when a devastating earthquake flattened San Francisco in 1906. Afterward, the northern San Andreas Fault, the state's massive earthquake-maker, lay quiet for eight decades — until 1989's Loma Prieta quake, which shook up the 1989 World Series game at Candlestick Park.

But it turns out that Northern California's earthquake lull may be an anomaly.

In the 70 years before the 1906 earthquake, the San Andreas Fault unleashed three earthquakes bigger than magnitude-6 in the Santa Cruz Mountains south of San Francisco, researchers report in this month's issue of the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. [Album: The Great San Francisco Earthquake]

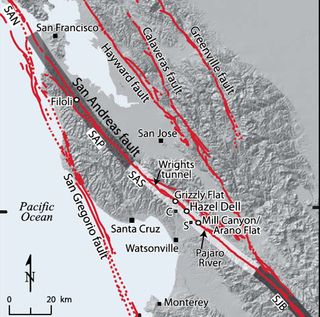

Geologists show that two quakes bigger than magnitude-6, centered near Corralitos, rattled early settlers, one in 1838 and one in 1890. The team also found signs of even more early temblors, including one in 1865. That means that the northern San Andreas Fault's earthquake pattern may be different than previously thought.

"The model for the fault was always fairly large but fairly infrequent earthquakes," said lead study author Ashley Streig, a geologist at the University of Oregon. "What we're seeing is the Santa Cruz Mountains segment rupturing more frequently," Streig told Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.The findings are another nail in the coffin for the notion that earthquakes strike like clockwork in California. In the early decades of earthquake science, researchers thought all earthquakes recurred at regular intervals, but in recent years, detailed studies are proving that model wrong in many cases. For example, earthquakes may cluster in time, or faults may go quiet after giant quakes, like the deadly 1906 San Francisco shocker.

"Earthquake recurrence is very variable, and that's what we're seeing," Streig said.

Quake chaos

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Before Streig's study, scientists had suspected the San Andreas caused the 19th-century earthquakes, based on historical records. But because Northern California is riddled with faults, there were many other potential culprits. (California has a lot of earthquake faults because it is the boundary between two tectonic plates, the North America and Pacific. The San Andreas Fault marks this boundary.)

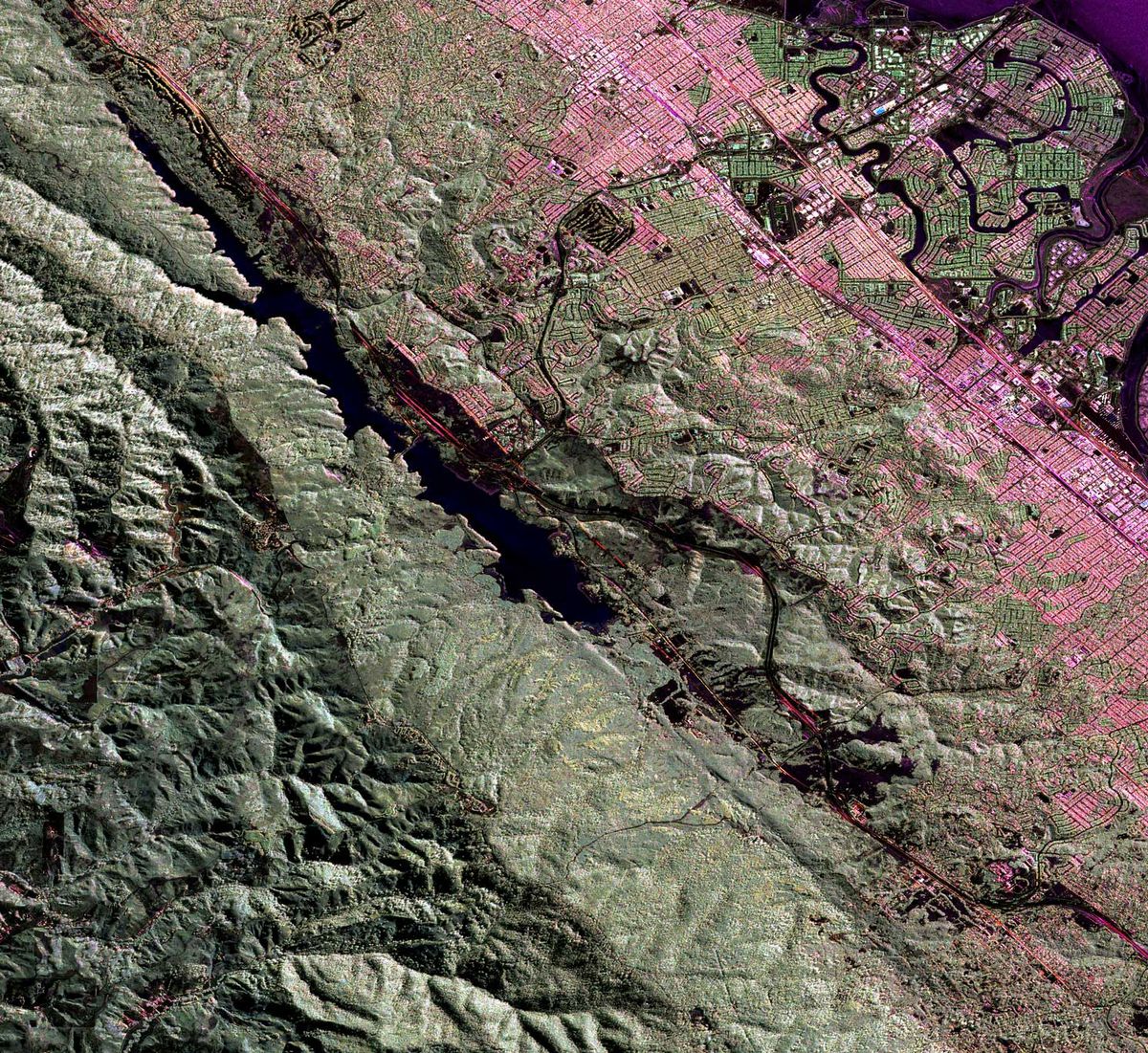

Streig and her co-authors pinned the past earthquakes on the San Andreas by examining sediment and wood in 16 trenches across the fault, all in the central Santa Cruz Mountains. Within the trenches, they found redwood chips and stumps from logging by Spanish settlers, and charcoal that could be analyzed with high-resolution radiocarbon dating. The wood age, combined with sediment analysis, confirmed that the ground surface suffered fissures and fractures during the earthquakes.

The researchers also found hints of two more ancient earthquakes before 1300, in addition to the 19th-century quakes.

By excavating at several sites, the team could also gauge how far the fault broke, or ruptured, during each earthquake. Combined with the historic damage accounts, this distance provides an estimate of each quake's size.

The 1838 earthquake was between magnitude 6.8 and 7.2 and the 1890 quake was between magnitude 6.2 and 6.4, the team estimates. For comparison, the 1989 Loma Prieta quake, also in the Santa Cruz Mountains, was a magnitude 6.9. Each of the 19th-century quakes ruptured a short segment of the San Andreas, some 48 to 62 miles (62 to 100 kilometers) long. The 1906 quake, estimated at magnitudes from 7.7 to 7.9, ruptured the ground for 296 miles (476 km).

Quiet in the west

The study fills a gap in the fault's history — the frequency of past quakes on the San Andreas Fault had been detailed to the north and south of Streig's study site, but never in this stretch of contorted crust. Streig said the results suggest the Santa Cruz Mountains segment of the San Andreas may be a transition zone, shaking more often than other portions of the fault. To the south, the fault creeps, sliding without locking and triggering earthquakes. To the north, along the San Francisco Peninsula, earthquakes seem less frequent, striking every 300 years or more.

Streig thinks the giant 1906 earthquake temporarily shut down the repeated rattling in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A similar quiet period may exist in older Santa Cruz trench earthquakes, but needs better testing, the researchers said. Streig plans to search for a longer earthquake record to test her model. "You can have a period like the early settlers saw, when there was really heightened activity, or you can have things shut down, which is what we've seen since 1906," she said.

"We're really looking at a snapshot of a short period in time," Streig said. "A longer record would be really nice to further test that transition zone model."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.