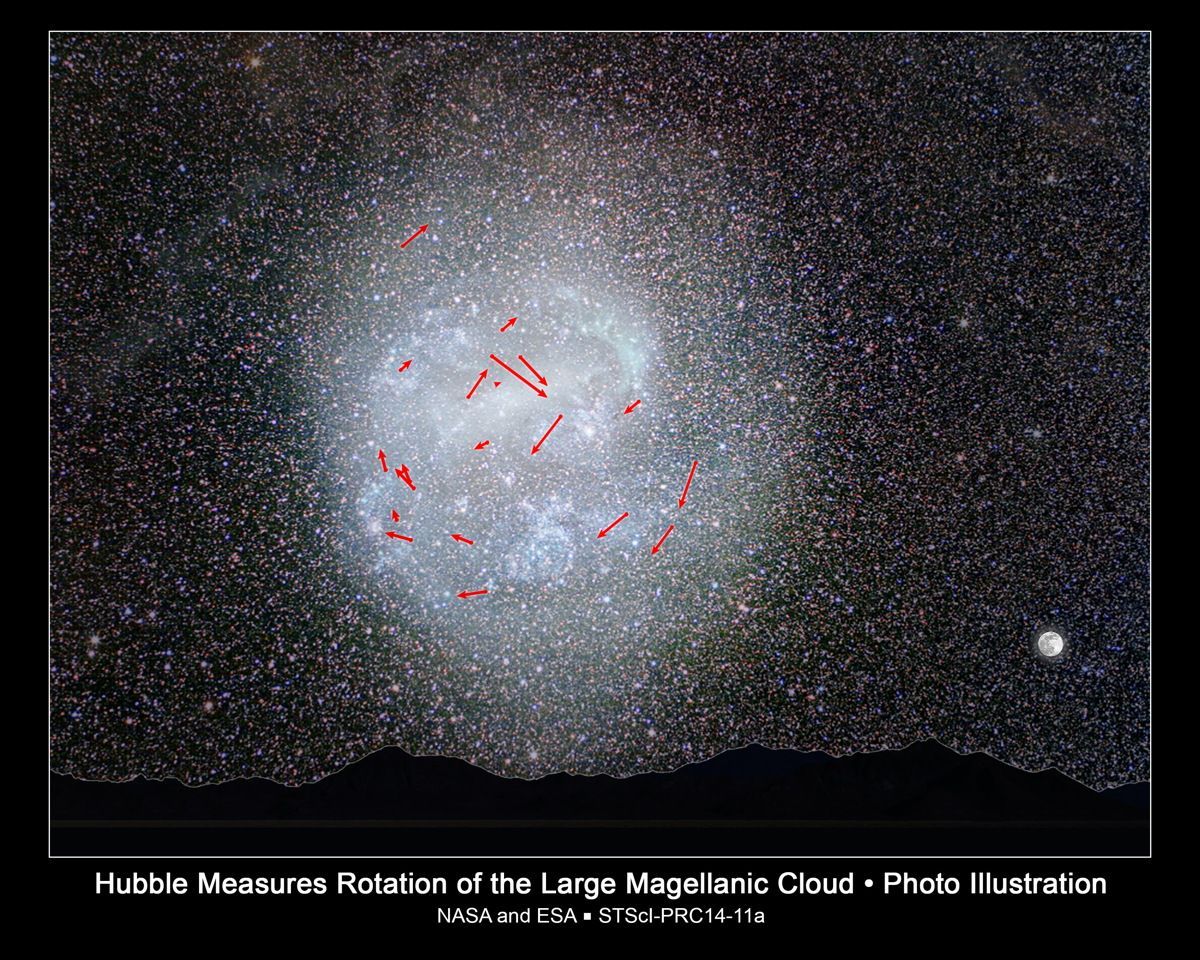

For the first time, astronomers have precisely calculated the rotation rate of a galaxy by measuring the tiny movements of its constituent stars.

Observations by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope reveal that the central part of the nearby Large Magellanic Cloud galaxy (LMC) completes one rotation every 250 million years — coincidentally, the same amount of time it takes the sun finish a lap around the core of our own Milky Way.

"Studying this nearby galaxy by tracking the stars' movements gives us a better understanding of the internal structure of disk galaxies," study co-author Nitya Kallivayalil, of the University of Virginia, said in a statement today (Feb. 18). "Knowing a galaxy's rotation rate offers insight into how a galaxy formed, and it can be used to calculate its mass." [Hubble Space Telescope's Latest Cosmic Views]

![Find out how Hubble has stayed on the cutting edge of deep-space astronomy for the past 20 years here. [See the full Hubble Space Telescope Infographic here.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/2kCs49ab4Y4ZXhvZiAycsL-320-80.jpg)

The Large Magellanic Cloud is one of the Milky Way's nearest neighbors, located just 170,000 light-years away. The LMC has a central bar but an irregular shape, suggesting that it was once a Milky Way-like spiral that has been bent out of shape by gravitational interactions.

In the new study, the research team used Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 and Advanced Camera for Surveys to measure the motion of hundreds of LMC stars over a seven-year period. Hubble is the only instrument precise enough to make such observations, scientists said.

"This precision is crucial, because the apparent stellar motions are so small because of the galaxy's distance," lead author Roeland van der Marel, of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said in a statement. "You can think of the LMC as a clock in the sky, on which the hands take 250 million years to make one revolution. We know the clock's hands move, but even with Hubble we need to stare at them for several years to see any movement."

The new Hubble data complement previous observations of the LMC, which estimated the galaxy's rotation rate by measuring shifts in the spectrum of its starlight, researchers said. (The light from stars moving toward Earth shifts slightly toward the blue end of the spectrum, while that from stars receding from our planet appears redder.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The LMC is an attractive target for astronomers interested in galactic structure and evolution, since it's close enough to observe in detail but far enough away to take in completely.

"The LMC is a very important galaxy because it is very near to our Milky Way," van der Marel said. "Studying the Milky Way is very hard because everything you see is spread all over the sky. It's all at different distances, and you're sitting in the middle of it. Studying structure and rotation is much easier if you view a nearby galaxy from the outside."

The new study was published in the Feb. 1 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.