Famous Star Explosion Lit by Ultrafast Mach 1,000 Shock Wave

Astronomers studying the remnants of a well-known stellar explosion discovered a blisteringly fast shock wave that is rushing inward at 1,000 times the speed of sound, lighting up what remains of the powerful cosmic explosion.

When a star reaches the end of its life, it explodes in a supernova that can briefly outshine entire galaxies. Typically, these blasts fade away after a few weeks or months, but the material left behind from these violent explosions can continue to glow for hundreds or thousands of years. Scientists have now observed a formidable inward-racing shock wave that keeps one of these stellar corpses glowing.

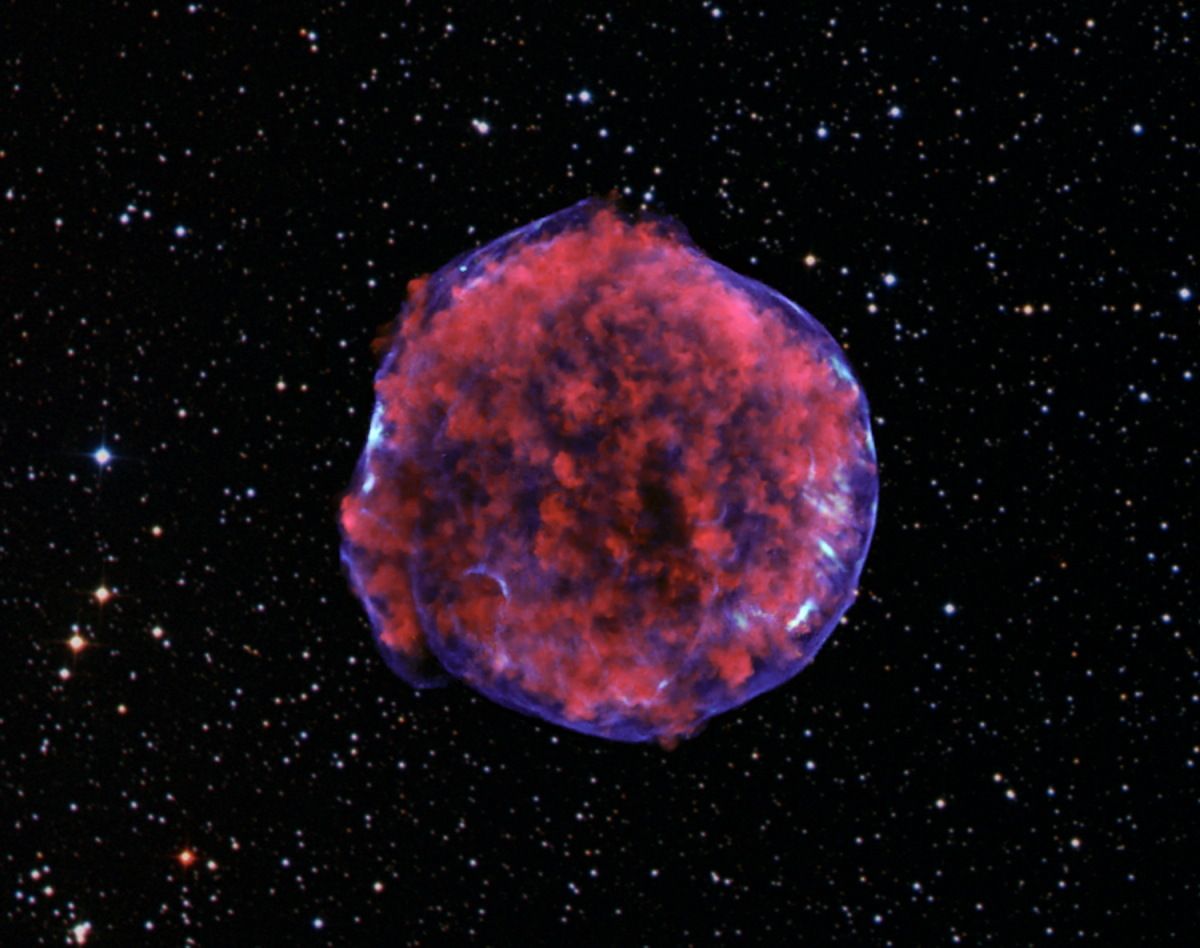

This so-called reverse shock wave is traveling at Mach 1,000, or a thousand times the speed of sound, heating the remains of the famous supernova SN 1572 and causing it to emit X-ray light, the researchers said. [Supernova Photos: Great Images of Star Explosions]

"We wouldn't be able to study ancient supernova remnants without a reverse shock to light them up," study leader Hiroya Yamaguchi, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., said in a statement.

SN 1572, otherwise known as Tycho's supernova, was a star that erupted in a brilliant explosion in November 1572. The supernova — named for Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, who studied it extensively — is located about 10,000 light-years away in the constellation Cassiopeia.

The blaze from Tycho's supernova was so luminous it could be seen with the naked eye, and the appearance of this "new star" in the sky confounded many people at the time who believed the heavens were fixed and unchanging. At its brightest, the supernova blast rivaled the planet Venus, and the explosion remained visible for 15 months before eventually fading from sight.

Tycho's supernova was a Type Ia supernova, which occurs when a white dwarf star in a close binary system accumulates matter from its neighbor until a runaway nuclear reaction ignites. The resulting cataclysmic explosion spewed elements, such as silicon and iron, into space at speeds of more than 11 million miles per hour (17.7 million kilometers per hour), the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As this expelled material impacted the surrounding interstellar gas, it created a shock wave that functions similar to a cosmic sonic boom. This shock wave is still expanding today, swelling outwards at 300 times the speed of sound, according to the researchers. These dynamics also triggered a reverse shock wave that is traveling inward at Mach 1000.

"It's like the wave of brake lights that marches up a line of traffic after a fender-bender on a busy highway," study co-author Randall Smith, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a statement.

The ultrafast reverse shock wave is heating the gases within the burnt-out husk of the former star, causing it to glow. This process is similar to how fluorescent light bulbs work, except the supernova remnant glows in X-rays instead of visible light, the researchers explained.

As such, the shock wave from Tycho's supernova helps astronomers study the remains of this famous cosmic explosion hundreds of years after it occurred. "Thanks to the reverse shock, Tycho's supernova keeps on giving," Smith said.

The researchers intend to search for signs of similar reverse shock waves in other supernova remnants.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.