Scientists have found the exact source of Stonehenge's smaller bluestones, new research suggests.

The stones' rock composition revealed they come from a nearby outcropping, located about 1.8 miles (3 kilometers) away from the site originally proposed as the source of such rocks nearly a century ago. The discovery of the rock's origin, in turn, could help archaeologists one day unlock the mystery of how the stones got to Stonehenge.

The work "locates the exact sources of the stones, which highlight areas where archaeologists can search for evidence of the human working of the stones," said geologist and study co-author Richard Bevins of the National Museum of Wales. [In Photos: A Walk Through Stonehenge]

Mysterious megaliths

The Wiltshire, England, site harbors evidence of ancient occupation, with traces of pine posts raised about 10,500 years ago. The first megaliths at Stonehenge were erected 5,000 years ago, and long-lost cultures continued to add to the monument for a millennium. The creation consists of massive, 30-ton sarsen stones, as well as smaller bluestones, so named for their hue when wet or cut.

Stonhenge's purpose has long been a mystery, with some arguing it was a symbol of unity, a memorial to a sacred hunting ground or the source of a sound illusion.

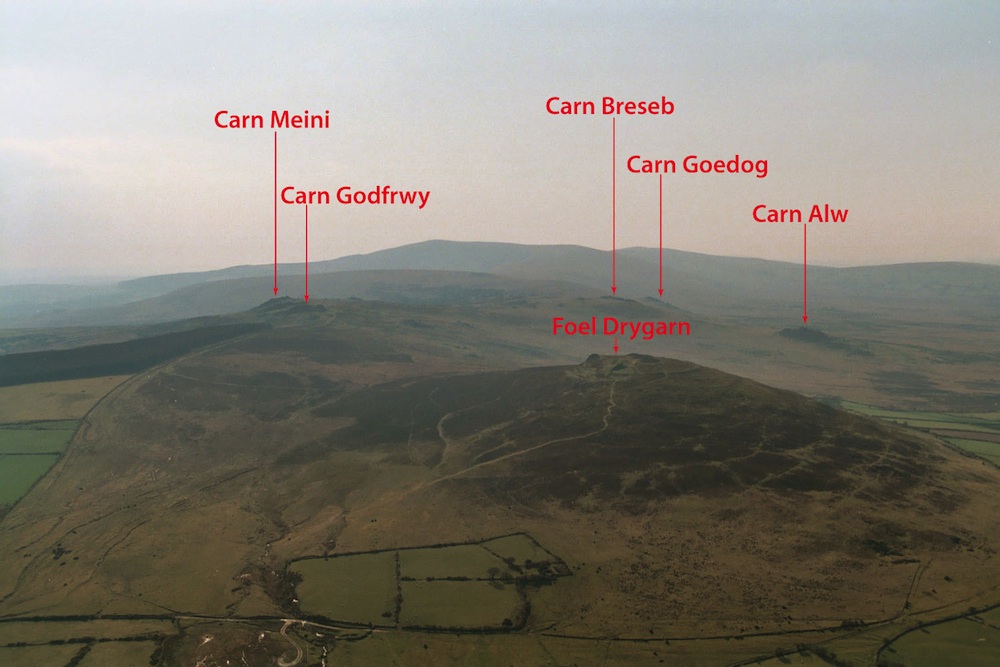

But for decades, researchers agreed upon at least a few things. In 1923, geologist Herbert H. Thomas pinpointed the source of one type of the stones, known as dolerite bluestones, to a rocky outcropping known as Carn Meini on high ground in the Preseli Hills of western Wales. He became convinced the other bluestones (made from other types of igneous, or magmatic, rock) came from the nearby location of Carn Alw. That, in turn, lent credence to the theory that Stonehenge's builders transported the stones south, downhill, to the Bristol Channel, then floated them by sea to the site.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Different origins?

But a few years ago, Bevins and his colleagues found that at least some of the bluestones came from a slightly different region of the landscape, at lower elevation, called Craig Rhos y felin. If true, this would have meant builders would have to the stones uphill over the summit of the hills, then back downhill before floating them on rafts to the sea, Bevins said.

Another competing theory argues glaciers carried the bluestones to the general region of Stonehenge during the last Ice Age.

The researchers wondered about the origins of the dolerite bluestones that Thomas had identified, and took a second look at the mineral composition of the rocks. In general, when rock forms from molten magma, some minerals known as incompatible elements remain outside the crystallizing magma in residual magma, whereas others get embedded within the crystallizing magma. Past work identifying the origins of the rocks had used the presence of only a few incompatible elements, Bevins said.

In the new study, the team looked at the minerals, such as chromium, nickel, magnesium oxide and iron oxide, which are part of the crystallizing structures forming in the original magma. The researchers found that at least 55 percent of the dolerite bluestones came from a location, known as Carn Goedog, which is farther north than the location Thomas had proposed in 1923, and about 140 miles (225 km) away from Stonehenge, Bevins said.

That, in turn, made the raft-theory of transportation more unlikely, Bevins told Live Science.

Transportation mystery

The new findings raise more questions than answers about how the rocks could have made it to Stonehenge.

But pinpointing the exact location of the stones' origins could help archaeologists looking for other evidence of ancient human handiwork near the area, which could then shed light on the transportation method, Bevins said.

"For example, if we could determine with confidence that the stones had been worked by humans in Neolithic times, then the ice-transport theory would be refuted," Bevins said.

The findings were published in the February issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.