The Amount of Hidden Sugar in Your Diet Might Shock You (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Added sugar in our diet is a very recent phenomenon and only occurred when sugar, obtained from sugar cane, beet and corn, became very cheap to produce. It’s a completely unnecessary part of our calorie intake: it has no nutritional value, gives no feeling of fullness and is acknowledged to be a major factor in causing obesity and diabetes both in the UK and worldwide.

The food industry is adding more and more sugar to food, which consumers are largely unaware of, as it is mostly hidden.

While it may not be surprising that a can of Coca Cola has a staggering nine teaspoons of sugar (35g), similar amounts can be found in the most unlikely of foods, including flavoured water (Volvic Touch of Fruit Lemon/Lime 27.5g per 500ml), yogurts (Yeo Valley Family Farm 0% Fat Vanilla Yogurt 20.9g per 150g pot), canned soup (Heinz Classic Tomato Soup 14.9g per 300g portion), ready meals (Pot Noodle Curry King Pot, 7.6g per portion) and even bread (Hovis Soft White Bread, 1.4g in one medium-sized slice).

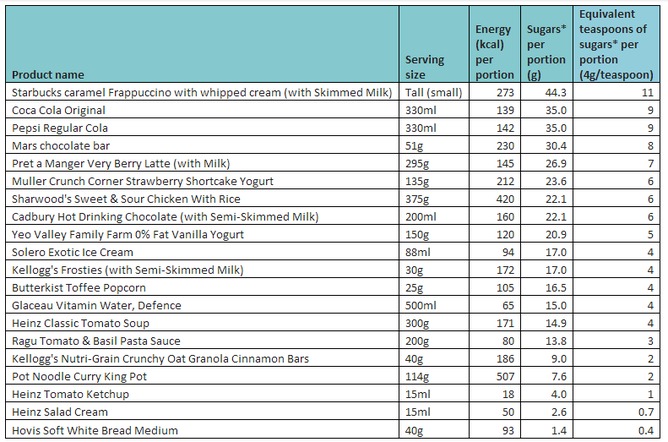

You might opt for 0% fat in your yoghurt but what if it also comes with five teaspoons of sugar? Or how about these:

It’s clear this sugar plays a part in soaring levels of obesity and diabetes. To this end, leading health experts from across the globe have united to tackle – and to unmask hidden sugar so consumers can make informed decisions about what they eat and drink.

It follows a similar model to salt reduction pioneered by Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH), which has been successful in compelling companies and manufacturers to add less salt to products over a period of time by setting targets for the food industry and mobilising public information.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Salt content in food products in the supermarkets have now been reduced by 20-40% and as a result, salt intake has fallen in the UK by 15% (between 2001-2011), the lowest known figure of any developed country. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), this will have reduced stroke and heart attack deaths by a minimum of 9,000 per year, with a saving in health care costs of at least £1.5bn a year.

A similar programme of gradually reducing the amount of added sugar in food and drink products, with no substitution in food, could prove to be an equally effective and practical way of reducing added sugar in the UK diet. As with salt, a 20-30% reduction in sugar added to food and soft drinks could be achieved over the course of five years, and result in a reduced calorie intake of approximately 100kcal a day, going some way to help reverse obesity rates.

There are several parallels between salt and sugar. Like salt, most of the sugar we consume is hidden in processed food and soft drinks. There are also specific taste receptors for sugar, which if sugar intake is gradually reduced become more sensitive. So over time we don’t notice that sugar levels have gone down.

If we can persuade the Department of Health that this programme is very likely to help considerably with the obesity epidemic, and in particular to reduce childhood obesity, while also reducing the incidence of dental disease, and (very likely) the number of people developing Type 2 diabetes, it should have a good chance of success.

Graham MacGregor set up and is Chairman of both Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH) and World Action on Salt and Health (WASH). He is also chairs the Blood Pressure Association, sits on the board for the World Hypertension League and recently served as President of The British Hypertension Society

Sonia Pombo is a member of Consensus Action on Salt & Health (CASH).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.