5 California Children Infected by Polio-Like Illness

Over a one-year period, five children in California developed a polio-like illness that caused severe weakness or paralysis in their arms and legs, a new case study reports.

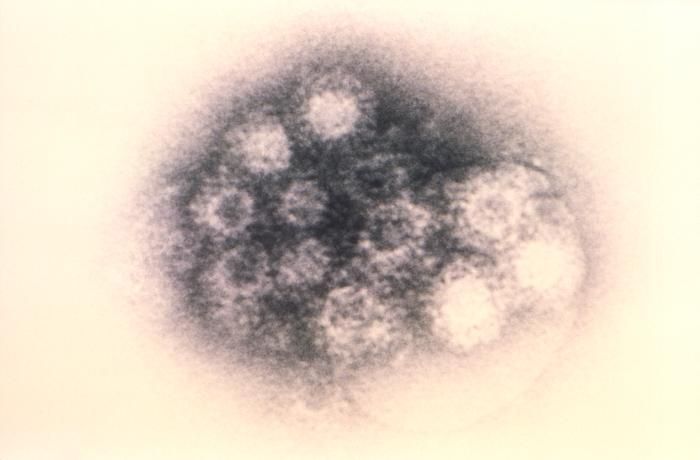

In two of the children, their symptoms have now been linked with an extremely rare virus called enterovirus-68.

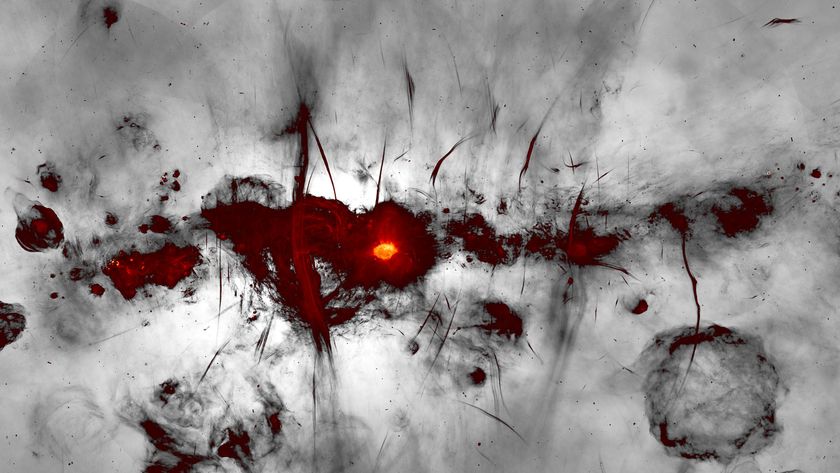

Like the poliovirus, which has been eradicated in the U.S. since 1979 thanks to the polio vaccine, strains of enterovirus in rare cases can invade and injure the spine.

These are the first reported cases of polio-like symptoms being caused by enterovirus in the United States. During the last decade, outbreaks of polio-like symptoms have been reported in children in Asia and Australia, and these infections have been associated with newly identified strains of enterovirus.

"We think one reason why these cases may have occurred in California is that we are at the western-most part of the United States, so we may have had a higher circulation of the virus that was originally identified in Asia," said Dr. Emmanuelle Waubant, co-author of the case report and a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Although two of the children tested positive for enterovirus-68, the researchers were not able to identify the cause of muscle weakness and paralysis in the other three children.

The researchers saw these children too late in the game to detect the actual virus, Waubant explained. "It could have been enterovirus, or it may have been another virus," she told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings were presented today (Feb. 23) at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in Philadelphia.

Extremely rare virus

"It's very likely that the vast majority of people infected with enterovirus will be fine," Waubant said. Most never develop neurological problems because the virus usually stays in the respiratory tract, where it may cause flu-like symptoms.

In only a very small percentage of people, the virus spreads to the spinal cord and damages nerve cells, resulting in weakness in one or more limbs, or paralysis, Waubant said.

After seeing a few cases of polio-like symptoms in children in their Northern California medical centers, the researchers wanted to find out whether similar symptoms had been reported in kids elsewhere in the state.

So they reviewed all the biological samples and medical histories of cases resembling polio that were referred to a statewide neurological and surveillance testing program between August 2012 and July 2013.

During this one-year period, they identified five cases of polio-like syndrome in California children ages 2 to 16.

Three kids had a respiratory illness before their neurological symptoms developed. All five of the children experienced sudden weakness or paralysis in one or more of their arms or legs that reached its peak severity within 48 hours.

The researchers did not include in their analysis children whose paralysis was known to result from other health problems, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome or botulism.

All five kids had been previously vaccinated against polio.

Increasing awareness

"These cases highlight the possibility of an emerging infectious polio-like syndrome in California," the report concluded.

Although the youngsters received treatment for their symptoms, it had little benefit. "Some of the children have improved a tiny bit, but most have not," Waubant said. Whatever weakness they developed from the illness, they still have, she added.

That's why Waubant said it's important to increase awareness of enterovirus among physicians — so when they see cases of polio-like symptoms in children, they know what it is and can diagnose it early.

By informing the medical community about the virus, doctors can send saliva and nasal swab samples to the appropriate labs who can look for and identify these types of viruses.

"Identifying the bug first is a top priority," Waubant said.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.

In a 1st, trial finds vitamin D supplements may slow multiple sclerosis. But questions remain.

Simple blood tests could be the future of cancer diagnosis