Jonathan Allen is a professor in the Department of Biology at the College of William & Mary. His teaching, as well as his research, is directed at marine invertebrates and he participates in the William & Mary Marine Science minor. Allen contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

This is a story that just might keep you up at night. One night in September last year, I woke up at 3 a.m. with a feeling that something just wasn't right. I am a scientist, and therefore not the kind of person who goes down the rabbit-hole looking to self-diagnose a rare disease, but there I was, night-surfing internet health sites trying to figure out what was behind the strange rough spot in my mouth.

Morning, as it often does, saw a return to normal in both mouth and outlook. But then, a couple days later, the bump came back. And it had moved.

As the roaming bump came and went from day to day, I grew increasingly concerned. Midnight conversations with my sleeping wife did little to address the issue. I began to wonder if some kind of parasite might explain the wandering rough patch in my mouth. Unfortunately for me, whatever was causing my symptoms liked to wander around in places I couldn't see, and it would stay that way for three full months. This was starting to keep me up at night.

By training, I'm an invertebrate biologist. In my job as a biology professor at the College of William and Mary, I teach students about the 98 percent or so of animal species that don't have a backbone. Many of these animals are charismatic, in their own spineless way: sea urchins, starfish, corals, jellyfish, etc. Those that aren't charismatic are often tasty: crabs, lobsters, clams, oysters — you get the picture. Despite their inherent beauty and palatability, it can be challenging to engage students in these largely foreign animals — but I've found that lecturing about invertebrate parasites never fails to garner a rapt audience.

Invertebrates, or any organisms, that make humans their home are inherently of interest to people. In general, we know a great deal about the organisms that make a living inside of us. In fact the symbol of the medical profession, the rod of Asclepius, is rumored to be an ancient symbol of a parasitic worm being spun out of the human body on a stick (a technique still used to this day to cure Guinea worm infections). You might therefore reasonably expect that parasites are both easily detected and widely known by medical professionals. You'd be wrong on both counts.

After three months of intermittent symptoms, I self-diagnosed myself in late December last year. It happened to be the day of the final exam for the Invertebrate Biology class I teach. The rough patch that had been migrating around my oral cavity for three months had moved to my lower lip. A few minutes in the bathroom with my camera confirmed my suspicions of a parasite. I could actually see the worm; it had moved, at last, into my lip. The sinusoidal shape of my parasite pal told me it was a nematode worm and a quick internet search (armed with the right information, those internet health websites switch from the refuge of hypochondriacs to the halls of modern medicine) suggested a likely candidate: Gongylonema pulchrum.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The only problem with my diagnosis is that G. pulchrum is exceedingly rare (we're slipping back towards hypochondriac land) with fewer than 60 cases reported globally. Nonetheless, armed with photographs of the worm in my lip and a handful of recent case studies, I felt confident I could make the case to my doctor. The thought crossed my mind that if I got a medical professional to help me with the diagnosis, we might even write it up as a case study ourselves.

My delusions of grandeur were quickly squashed when my primary care physician (or more accurately his answering service) told me he didn't deal with something like this. A referral to an oral surgeon yielded no better results: my symptoms were simply normal discoloration of the oral mucosa, and in fact, he sees this sort of thing "all the time."

Luckily for me, another cause of late night sleeplessness (a three-year-old learning to use the potty) gave me the opportunity for a little bit of self-surgery. The rough spot had moved to a place I could reach with some forceps.

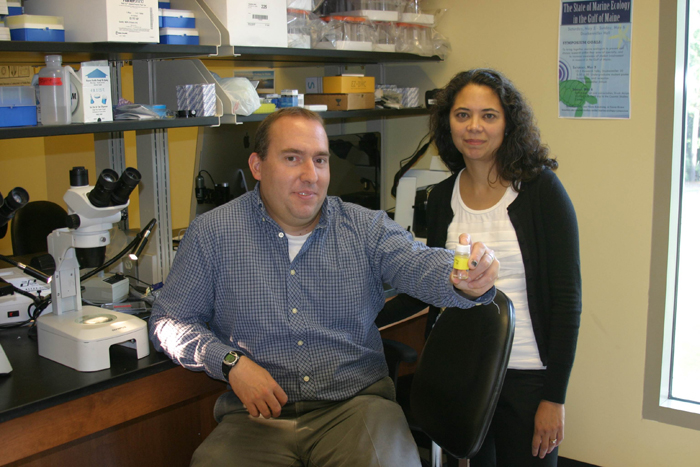

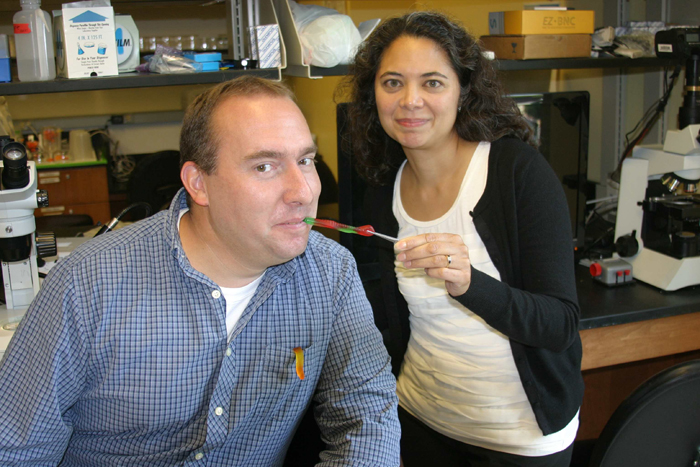

I woke my wife and asked her to hold the flashlight in the bathroom mirror while I pulled the worm from my cheek. Once removed, I rushed to my research lab to document my find: an intact and very lively specimen of G. pulchrum. Like other Christmas presents, it came only when everyone else was asleep. And yes, I was still in my pajamas.

One last piece of serendipity: My neighbor, Aurora Esquela-Kerscher, is a biologist at Eastern Virginia Medical School, and she happens to be one of the few people in the world qualified to sequence DNA from a small worm like mine. With Aurora's unique skill set, and my unique parasite, we teamed up to publish a case study in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. I wonder if my physician is a subscriber?

The publication of our case study opened up a world of opportunities to talk about my new friend (appropriately named 'Buddy'). Buddy and I had the good fortune to be featured in a piece by a Pulitzer-prize winning writer, Deborah Blum, in her column at Wired. That piece was a gateway to even more attention, leading to a story and video segment on the Huffington Post and countless re-tellings of the stories on blogs and news websites across Europe, Asia and beyond. Aurora and I also got a grant to study the prevalence of Buddy-itis (if you will), which is largely asymptomatic.

Why were folks so interested in the story of Buddy? I think it struck a chord with people who can identify with that 3 a.m. health worry. The likelihood that Buddy was acquired from ordinary food and water sources provides a bit of a horror-movie thrill, if no comfort. Add in a less-than-ideal interaction with medical professionals, and you have a perfect storm of cultural touchstones that transcends national borders.

What do I take away from this ordeal? As a patient, the saga of Buddy has eroded some of my faith in our health care system. If it takes more than a Ph.D., images of the parasite and a slew of research articles to get a correct diagnosis, what hope can most folks have?

As a professor, I've thought a great deal about what this means for how I train my students. At the collegiate level, its common to hear schools emphasize that we train people how to think and deal with the unpredictable problems of the future. My case study is an example of how that skill set is still too rare, even among highly educated medical professionals. I think the fundamental thing that this ordeal has convinced me of is that my job as an educator is more important now than ever.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.