High-Tech Exosuit Lets Scientist Divers Explore Underwater Canyons

Remember that scene in "Aliens" where Sigourney Weaver's Ellen Ripley dons a Power Loader exoskeleton to do battle with the evil alien queen? Yeah, that was nothing.

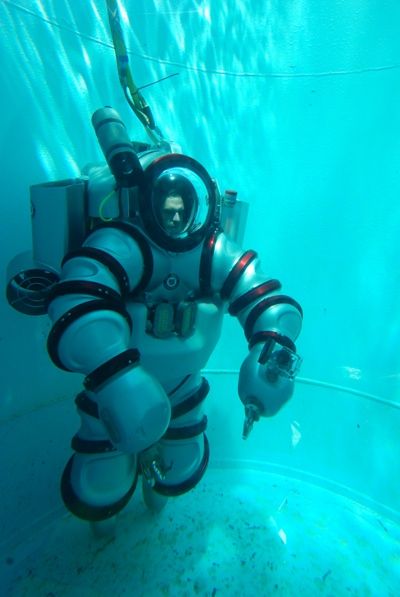

Marine biologists and engineers have now developed a massive Exosuit weighing 530 lbs. (240 kilograms) designed for ocean depths down to 1,000 feet (305 meters) — another extreme environment where no one can hear you scream.

Researchers will take the Exosuit on its maiden journey this July, when they will use it to take samples and conduct imaging studies of the animals that live in "The Canyons," a region off the New England coast where the continental shelf plunges to depths of more than 10,000 feet (3,050 m). [Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures]

The one-of-a-kind Exosuit, on display at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) now through March 5, measures 6.5 feet (2 meters) tall and is made of hard metal and other materials. The pressurized suit has four 1.6-horsepower thrusters to propel the diver up, down, forward, backward or to the side.

Additionally, the Exosuit — with an oxygen system that provides up to 50 hours of life support — is equipped with a fiber-optic tether that allows for two-way communication, oxygen and pressure monitoring, and a live video feed.

The researchers on the July expedition will study bioluminescence and biofluorescence in the mesopelagic zone, found at 656 to 3,281 feet (200 to 1,000 m) below the ocean's surface, where light is dim and pressure can be 30 times greater than at the surface.

Bioluminescence is the light created by living organisms through a chemical reaction in the creatures' bodies. Biofluorescence, on the other hand, occurs when organisms absorb high-energy, short-wavelength light (such as ultraviolet light), then re-emit that light at a longer wavelength. This process makes the organisms appear to glow with an eerie, colored light (often green or red).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Earth's greatest migration

Billions of marine animals migrate vertically on a daily basis from deep within the ocean's darkest abysses to the surface, where they feed at night, only to drop thousands of feet back to the depths before dawn. Scientists have called this mass migration — known as diel vertical migration or DVM — the largest migration on Earth.

Many of these migrating fish, plankton and other animals have bioluminescent or biofluorescent properties, but scientist have only studied them with remote instruments or from samples found in trawl nets.

That's what makes the Exosuit a giant leap forward for marine biologists, who have never before been able to study these little-known organisms in their natural habitat.

"Our access to these deeper open-water and reef habitats has been limited, which has restricted our ability to investigate the behavior and flashing patterns of bioluminescent organisms, or to effectively collect fishes and invertebrates from deep reefs," John Sparks, a curator in the American Museum of Natural History's Department of Ichthyology, said in a statement. "The Exosuit could get us one step closer to achieving these goals."

The July expedition will be a collaboration among several groups: the J.F. White Contracting Company in Framingham, Mass., (which owns the Exosuit), the AMNH, the John B. Pierce Laboratory at Yale University, Baruch College-City University of New York, the University of Rhode Island and Arizona State University.

Follow Marc Lallanilla on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.