Did That Just Happen? How Your Brain Alters Mental Timelines

It sounds like a scene from a detective novel: The witness sees a body falling from the window, and then hears a loud noise that sounds like the body hitting the ground. But what if the noise actually came before the fall?

Navigating through our memories of past events seems to be easy task, but we don't always get it right. We might remember things that didn't happen, and we can also get the time wrong. We may remember incidents as happening closer together or farther apart than they actually did, or even completely mess up the order of events.

Exactly how the brain organizes memories in relation to each other in time has long puzzled scientists. In a new study, researchers set out to identify the nature of brain activity that puts a time stamp on our memories.

"Our memories are known to be 'altered' versions of reality, and how time is altered has not been well understood," said study researcher Lila Davachi, an associate professor of Psychology at New York University.

"People think their memories are a reflection of reality. They somewhat are, but they are a better reflection of what's happening inside their head," Davachi told Live Science. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

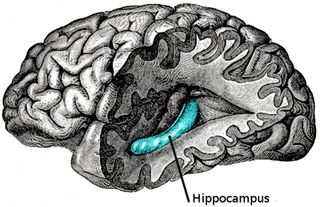

The new research shows a link between activity patterns in the hippocampus — a region known to be involved in forming memories — and how near or far away in time people placed their memories, according to the findings detailed Wednesday (Mar. 5) in the journal Neuron.

Did all that happen at one party?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To understand how people remember the order in which events occurred, the researchers had 21 study participants watch images of faces flash a few seconds apart, with an image of an outdoor scene flashing in between the faces. The idea was that the faces each represented an event, for example meeting a new person, and the scene represented where that event took place, for example in a party.

"We were trying to create stability in the environment, trying to mimic what it feels like when you go into a room or to a party and stay there for a long time," Davachi said. "The basic spatial context is the same, but you're seeing lots of different people."

Meanwhile, researchers used a brain-imaging technique, fMRI, to scan participants' brain activity in the hippocampus.

Participants later judged how close in time any two particular faces had appeared, rating them as very close to each other, close, far or very far apart. They didn't know that all pairs of faces had appeared at equal, 16-second intervals.

Researchers found that periods of stable activity patterns in the hippocampus lined up with participants saying that a pair of faces had appeared closer together in time.

By contrast, when the stability of the activity patterns was diminished, participants were more likely to recall the faces as having appeared further apart in time. In other words, stability of activity in the hippocampus gave a measure of how close together people remembered events in time.

Sometimes, however, researchers changed the scene. A different image was shown to the participants between the faces.

This pattern served to model a different real-life experience — "as if you walked out the door and into the street," Davachi said.

The researchers found that changing the scene, led people to later say that faces had appeared further apart.

"So [a new scene] shifts your memory for time," Davachi said. "All of these little changes help organize memories, and in a way that biases your memory for things that happened in the same context, so that they are placed closer in time." [Inside the Brain: A Photo Journey Through Time]

Time in the brain

Could this be how we perceive time? Scientists don't know, but Davachi said she thinks the process could have a role. "It should have an influence on the perceived duration of events, as well," she said, adding that future work is needed to better understand these mechanisms.

Insights into the temporal nature of how people store memories may offer ideas about some psychiatric problems, as well, Davachi said.

For example, people with schizophrenia may have an impaired ability to organize memories in time, and this could lead to making delusional connections between things that, in reality, are unrelated to each other.

"Delusions in schizophrenia usually take the flavor of sensing a causality in the world that's not there," Davachi said. It would be interesting to ask people with schizophrenia to participate in the experiments used in this study, to see whether a temporal memory impairment exists in this condition, she said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow us @LiveScience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.