Birds, Like Humans, Can Plan Ahead

Western scrub jays, perching birds common in California cities, store snacks when they detect that food will be in short supply the next day or in the near future, new research suggests.

Scientists had previously placed the skill of "future-planning" into the exclusively human category. Recent studies have revealed some planning smarts in primates such as apes, but most other animals were perceived as only capable of putting their immediate needs on center stage.

Even animals that may appear to recognize future needs, the scientists suggest, are actually reacting to instinctual cues, such as the case with nest building, or immediate needs like hunger, which can trigger food hoarding.

Nicola Clayton of the University of Cambridge and her colleagues set out to test whether scrub-jay birds could plan for a future need as opposed to a current one. On alternate mornings for six days, eight scrub jays experienced one of two compartments. In one compartment, the birds were always given breakfast and in the other they were not.

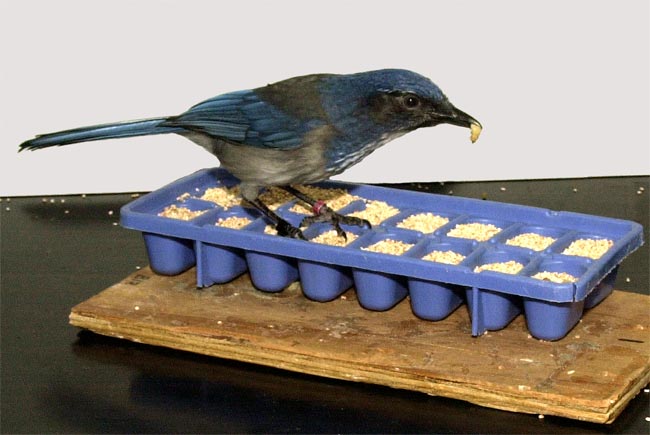

In the evening, after this training period, the scientists allowed the birds to feast freely on pine nuts, which are suitable for hoarding. The birds planned for a breakfast-free morning by hiding much more food in the bare compartment compared with the "breakfast" one [image]. The prudent squirreling away reveals an understanding of future needs, the researchers say.

In a similar experiment, the scrub jays hung out in either a compartment with peanuts or one with dog kibble on alternate mornings. After several days, the birds were allowed to travel between compartments. This time the forward thinkers planned for a balanced diet and buried peanuts in the kibble enclosure and kibble in the peanut compartment [image].

"The western scrub jays demonstrate behavior that shows they are concerned both about guarding against food shortages and maximizing the variety of their diets in the future," Clayton said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It suggests they have advanced and complex thought processes as they have a sophisticated concept of past, present and future, and factor this into their planning."

The research will be detailed in the Feb. 22 issue of the journal Nature.

- Video: Bird Radar

- Video: Extraordinary Birds

- Images: Rare and Exotic Birds

- Top 10 Animal Senses Humans Don't Have

More on Brainy Birds

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.