7 Ambitious Scientific Expeditions

Getting down and dirty

Who says science is all test tubes and equations? Sometimes, you've got to get your hands dirty to make discoveries. From the mapping of our planet to the exploration of space, here are seven scientific field expeditions that combined exploration and adventure.

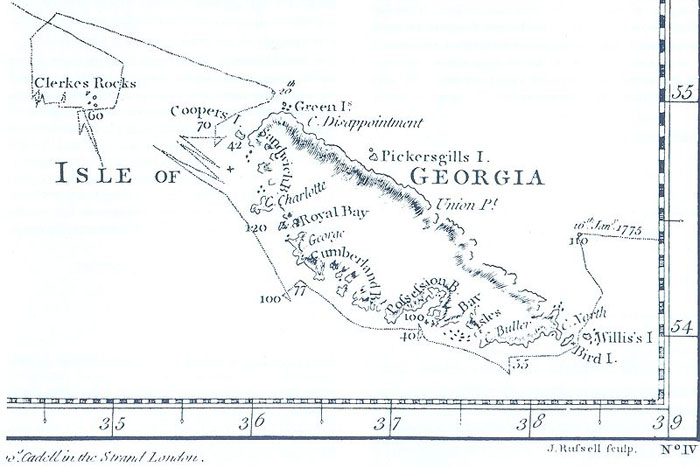

James Cook fills in the map

In a series of three voyages between 1768 and 1779, British explorer James Cook circumnavigated the globe, searched for the fabled Northwest Passage and discovered the Hawaiian Islands. But Cook was more than just a sea captain. He was a cartographer, and his adventures would fill in longstanding gaps on the world map.

On his first voyage, he discovered, claimed and mapped New Zealand for Britain; on his second, he explored the Antarctic, but turned north without discovering the continent itself. These southern explorations put to rest the popular belief that there was another Pacific continent somewhere between Australia and the South Pole (north of where Antarctica was eventually discovered). Before meeting his death on the Hawaiian Islands in 1779, Cook would cross the Antarctic Circle, map South Georgia Island and record the shape of the west coast of North America.

Lewis and Clark map the American West

In 1804, William Clark, Meriwether Lewis and their men set out on their famous cross-continental journey in search of a water route to the Pacific. They didn't find it, but they did manage to map the Northwest and catalogue hundreds of new plant and animal species.

Among these were the Clark's nutcracker, a ubiquitous, "squawling" bird, according to Lewis' account; the black-tailed Lewis Mule deer; and clarkia, a delicate, pale purple flower. The expedition also faced grizzly bears ⎯ "a most tremendious looking anamal," Lewis wrote in his journals ⎯ and sent a live prairie dog in a box back to President Thomas Jefferson.

John Wesley Powell surveys the Grand Canyon

John Wesley Powell was a lot of things: Civil War veteran, adventurer, second director of the U.S. Geological Survey. But at his core, Powell was a scientist. Just a year after he lost his right arm at the Battle of Shiloh, he was back in the trenches at Vicksburg, examining the rock strata around him and collecting fossil shells between skirmishes.

So it isn't surprising that the unmapped, unexplored Grand Canyon called to Powell. In 1869, he, his brother Walter and seven experienced mountain men launched four small boats into the Green River, heading south to meet up with the mighty Colorado.

The journey would take months and cover more than 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers). Whitewater rapids destroyed two of the expedition's boats. One man abandoned the voyage one month in; three others took off on foot just two days before the journey ended. (All three were killed, but their murderers were never identified.)

The remaining men emerged alive in Arizona three months after beginning their journey. Powell made no delay in planning a second trip for 1871. This time, he brought along a surveyor and a photographer. The team succeeded in bringing back the first topographic map of the canyon, hundreds of photographs and a deeper understanding of the arid western environment.

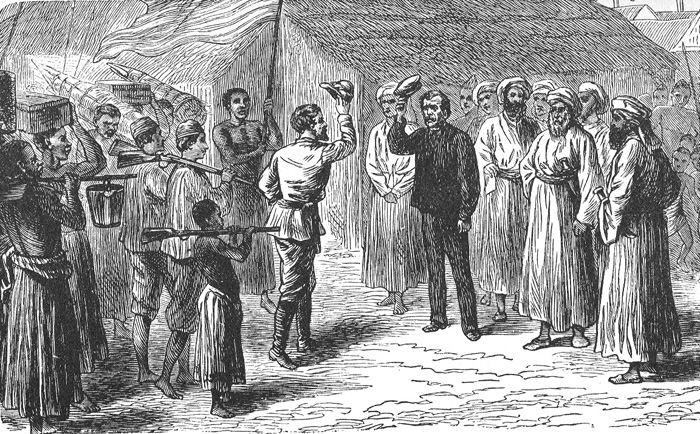

Livingstone and Stanley explore Africa

Missionary David Livingstone explored Africa during a time when Europeans couldn't get enough of what they called the "Dark Continent." Thanks to this Africa fervor ⎯ and Livingstone's reports, featuring his first view of the enormous Victoria Falls ⎯ the British government agreed in 1858 to fund his Zambezi expedition into southeastern Africa. The mission failed to find a navigable river route into the continent, but did return to England with pages and pages of reports on botany, ethnology and geography.

In 1866, Livingstone again managed to secure funding for a second expedition, this time to search for the headwaters of the Nile River. But soon, his team began to desert him, and his health failed. Rumor had it that he was dead. Eventually, he ended up in the village of Ujiji in what is now Tanzania, where U.S. newspaper reporter Henry Stanley found him and uttered the possibly-apocryphal greeting, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?"

The doctor refused to leave Africa with Stanley, and continued his quest for the Nile's headwaters. He died in 1873, never having reach his goal.

The Belgica winters in Antarctica

The Belgica, a retrofitted seal-hunting ship, steamed out of Antwerp, Belgium, in August 1897, so loaded down with equipment that her decks were just a few feet above water. The ship and her crew were headed to Antarctica, where they planned to map the location of the magnetic South Pole and return before the Antarctic winter blew in.

The plan didn't work out. The commander of the mission, Belgian Commandant Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery, made the decision to sail south in an attempt to beat the record for the southernmost journey. In February, the pack ice froze up around the ship, and the crew was forced to prepare for an unexpected winter in Antarctica.

Trapped without proper clothes or enough food, the men hunted penguin and watched the sun set for the final time in late May. After that, every day was dark. The men resisted eating the penguin until scurvy began to set in and a few seasoned crew members convinced the others that the blubbery meat would save their lives.

The vitamin C in the meat did indeed defeat the scurvy, but as the months wore on, the situation seemed more and more grim. By the next January, the ice showed no signs of breaking up, so de Gomery ordered his men to help it along. Using saws and dynamite, the crew broke a channel through the ice and made a grueling one-month journey back to open sea.

Despite all of their troubles, the team still managed to make scientific observations. Their unwilling winter exile even gave them the chance to record a year's worth of Antarctic meteorological data.

The Vostok 1 enters Earth's orbit

By the 1960s, scientists were looking to the stars for their next expeditions. The space race was on, and in 1961, the Russians won a significant skirmish: They sent a human being into space.

Cosmonaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin hurtled into orbit on April 12, 1961. Unmanned spacecraft (and crafts manned by dogs) had made the trip before, but the Russian air force prepared two press releases announcing the missions' failure, just in case.

Fortunately for Gagarin, they didn't have to use them. The ship entered orbit, and despite some communications difficulties, ran into no trouble during its 108-minute run. After a shaky re-entry, Gagarin landed in the Saratov province of Russia, reportedly shocking some local villagers in the process.

The success of this journey was less about bringing back scientific information and more about proving it could be done ⎯ and that the human body could handle it. "The state of weightlessness is no hindrance to a human being," a NASA report noted at the time. "He can eat and drink without any difficulties."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Man lands on the moon

When Neil Armstrong and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin, Jr., set foot on the moon on July 20, 1969, they were capping off the first half of the longest journey mankind has ever made. The moon orbits about 24,000 miles (380,000 kilometers) from Earth on average, and NASA estimates that the total distance traveled by the astronauts was 953,700 miles (1,533,175 kilometers).

The Apollo 11 astronauts spent 21 hours on the moon. Just over 2.5 hours of that was spent on the surface, exploring the area around the spacecraft. The crew deployed seismic monitors and a solar wind experiment. They also collected 47 pounds (21.5 kilograms) of lunar rocks and dust.

Five more manned NASA missions made it to the moon over the next three years, culminating with 1972's Apollo 17 mission. On that journey, 38-year-old astronaut Eugene Cernan re-entered the lunar module after his colleague, making him the last man to walk on the moon.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.