7 Craziest Land Journeys

Incredible journeys

It's easy to forget in the day of the airplane and the automobile, but most of the human exploration of planet Earth has been done on horseback and on foot. Some forays into the backcountry end in glory; others are a tragedy for everyone involved. Here are some of the wildest overland journeys in human history.

Zhang Qian opens the Silk Road

The year was 138 B.C., and the emperor of China was having border troubles. A hostile tribe of Central Asian nomads (known in China as the Xiongnu) kept attacking Han Chinese towns, ransacking and stealing goods. Frustrated, the emperor sent a military officer by the name of Zhang Qian west from the city of Xi'an in China to what is now Tajikistan with instructions to forge an alliance with another tribe, the Yuezhi.

Unfortunately for Zhang Qian, the path to Yuezhi lands let him right through the Xiongnu's domain. He was captured almost immediately and held for 10 years. Luckily, captivity was fairly cushy for Zhang Qian: The Xiongnu leader gave him a wife and gradually grew to trust him.

Zhang Qian eventually managed to escape, along with his wife and soldiers. Despite a decade of delay, he didn't give up on his mission: He and his men skirted the northern edge of the Tarim Basin and traveled through what is now the Xinjiang province to modern-day Tajikistan. The Yuezhi turned out to be uninterested in fighting the Chinese emperor's wars, but Zhang Qian was impressed by their advanced agriculture and strong horses. He made his way back to Xi'an ⎯ getting waylaid for another 2 years by the Xiongnu in the process ⎯ to tell the emperor of the opportunities for trade across the border. These reports would eventually contribute to the opening of the great Silk Road, a series of overland trade routes between East and West.

Coronado seeks out a city of gold

In 1540, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado y Luján, a wealthy estate owner and governor, set out from northwest Mexico looking for a fabled city of gold. This city, said to exist somewhere to the north, was known as Cibola, and given the riches of the Aztecs and Inca to the south, it seemed likely that natives to the north might also have treasure ripe for the taking.

Coronado took with him an army of hundreds of Spaniards and natives. They met and fought Pueblo Indians in what is now New Mexico and captured two native men, one of whom claimed that the fabled Cibola was farther north.

The expedition soon found itself tramping through the seemingly infinite grass of the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles. They faced a Great Plains hailstorm that ripped holes in their tents and dented their helmets. Eventually, they made it to a Wichita Indian village near what is now Lindsborg, Kan. To Coronado's chagrin, the only gold to be seen was the Indians' cornfields. He had his native informant executed and limped back to New Mexico, where he received a head injury after falling off his horse. He returned to Mexico, bankrupted by the two-year expedition, and died 10 years later in Mexico City.

Lewis and Clark map the American West

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out on their famous cross-continental expedition in 1804 in an attempt to find a water route to the Pacific. As it turned out, no such thing existed, but the 33-man expedition still managed to map the Northwest and catalogue hundreds of new plant and animal species.

Lewis and Clark had a lot of help from native informers in finding their way, but the journey was still difficult. During their first year, they wintered in North Dakota, where they recorded temperatures of minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 40 degrees Celsius). The next spring, a fork in the Missouri River forced the expedition to split up and travel dozens of miles in both directions to determine the right route. In Montana, they had to portage their canoes and equipment 18 miles (29 kilometers), a process that took a month and subjected them to hailstorms, clouds of mosquitoes and the ever-present threat of grizzly bears. Soon after, they traversed Montana's Bitterroot Mountains, where game was scarce and the men had to shoot and eat three of their own horses.

In the end, Lewis and Clark would make it to the Pacific and back with all but one of their men, who died of appendicitis. Upon their return, they were acclaimed as heroes and eventually made governors of some of the new territories they had explored.

Napoleon invades Russia

In 1812, Napoleon Bonaparte was at the height of his power. With all of Europe under his thumb, the French emperor turned his attention toward Russia. In June, he sent a force of between 400,000 and 600,000 men to take Moscow.

By the time the army entered the city, there was little left to conquer. The Czar and many of the city's residents had fled, burning any items of value they had to leave behind. In mid-October, unable to wait any longer for a surrender that never came, Napoleon and his forces made their retreat.

They had waited too long. The snows came early that year, burying the grass that would have fed the army's horses. When the army passed villages, the desperate animals tried to feed on the thatched roofs of houses, but most starved quickly. Soon enough, the soldiers began to starve, too. In the subzero temperatures, many simply froze to death. Far more died from hunger or cold than were killed in battle. In the end, Napoleon's 400,000 to 600,000-man army was reduced to a ragged, pitiful force of 20,000.

The Donner Party gets stranded

In the 1840s, thousands of American pioneers struck out to find their fortune in the West. Most took the well-worn Oregon Trail to Wyoming, after which they could choose one of several routes to California or Oregon. If all went well, the trip would take between four and six months. But in the spring of 1846, a man named Lansford Hastings thought he had a shortcut.

Hastings, an early pioneer, had published a guide for other travelers in which he recommended the Hastings Cutoff, a trail through Utah's Wasatch Mountains and Great Salt Lake Desert. By 1846, Hastings had only traveled this route once, without the heavy wagons used by pioneer families. Nonetheless, he sent emissaries east with letters urging émigrés to follow his directions for a quicker trip to California.

Among the recipients of this letter was the well-to-do Donner family. Along with eight other families and 16 single men, the Donners decided to take Hastings' route. This turned out to be a very bad decision.

The trail was nearly impassible, forcing the men in the party to hack through undergrowth and move boulders to create space for the wagons. Once they made it through the mountains, the pioneers had to face the arid salt flats of Utah, where they lost 36 oxen, several wagons and multiple supplies. By the time they reached the Sierra Nevada Mountains, winter had closed in.

What happened next is well known: Stranded, the party ate their livestock down to the hide and bones. When the animal flesh ran out, they turned to their own dead. By the time rescue parties arrived in February and March, bodies littered the pioneers' camps. Of the 87 members of the Donner Party who entered the Wasatch Mountains together, only 41 finished the journey.

Stanley seeks out Livingstone

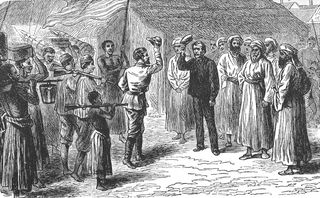

In 1840s England, David Livingstone was a celebrity. This missionary and explorer took the country by storm with his tales of Africa before disappearing in the so-called "Dark Continent" in the 1860s. The media was desperate to find him, so desperate that a New York Herald editor financed an expedition by reporter Henry Stanley to seek out the lost national hero.

Stanley launched his 200-man expedition from the Zanzibar coast (part of what is now Tanzania) in 1871. His goal was Lake Tanganyika, a great lake on the borders of what is now Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia and Tanzania. Despite his lavish funding, Stanley soon found that overland travel in Africa was tough. His horse died from a tsetse fly bite within days, his porters began to desert (perhaps as a result of brutal treatment by Stanley) and disease plagued the expedition.

After eight months, Stanley found his quarry in a village in what is now Tanzania. The two may or may not have had the famous "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" conversation ⎯ journalists in the Victorian era being prone to exaggeration ⎯ but they did explore Lake Tanganyika together before Stanley left Africa. Livingstone remained behind, and would die of malaria and dysentery two years later.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fridtjof Nansen attempts to reach the North Pole

In 1893, Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen did something odd: He froze his ship, the Fram, into Arctic pack ice and waited for the current to carry him to the North Pole.

After 18 months of drifting, Nansen went to Plan B. On March 14, 1895, he and his shipmate Hjalmar Johansen struck out for the pole on skis, taking three teams of sled dogs and three sleds to carry their supplies. They were 400 miles (640 km) from the pole with only 30 days' rations, and the terrain soon became rough. The pair got closer to the pole than anyone ever had, but after about three weeks, they realized they would never make it without starving to death.

The men turned back, aiming for the Arctic archipelago of Franz Josef Land. They traveled for weeks before finding signs of life ⎯ seals, gulls and whales. But they didn't know where they were, and winter was closing in. They found a sheltered cove and passed a frigid, dull winter holed up in a shelter made of stones and walrus bones. That spring, they set out again, finally reaching Cape Flora at the southern tip of the archipelago. There, they met another group of explorers, who returned them to a civilization that had largely given them up for dead.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.