Plankton Poo Plays Critical Role in Ocean's Twilight Zone

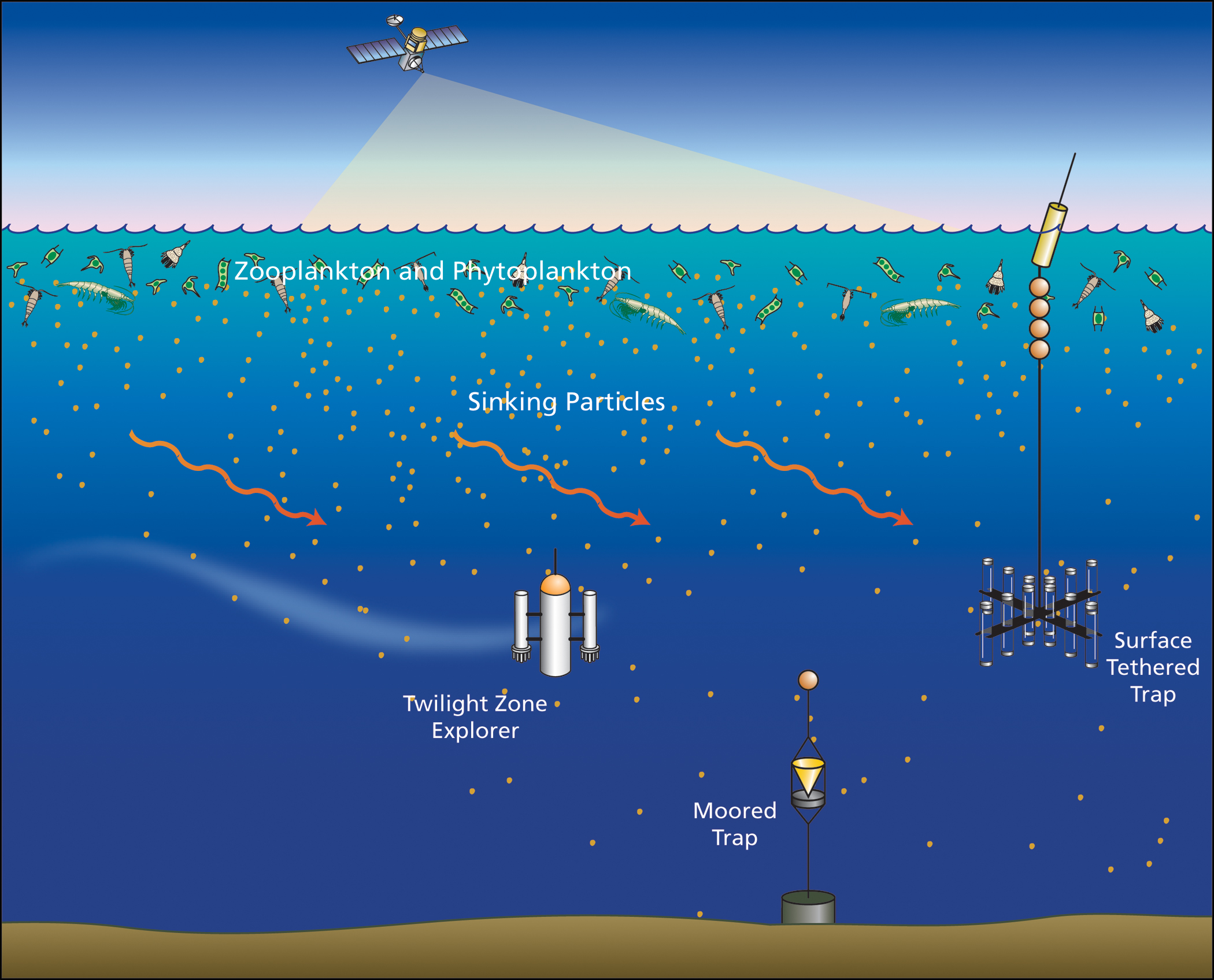

Journey through the ocean's twilight zone, where tiny marine creatures burn through tons of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, and one moves from light into shadow.

Here where sunlight dims, 330 to 3,300 feet (100 to 1000 meters) below the sea surface, tiny sea creatures transform carbon into forms bound for deep ocean storage. But until now, it was hard to pin down exactly how much carbon moved through this vast dimension. The creatures living in the twilight zone seemed too voracious, and estimates of their appetite for carbon outmatched the available supply.

In 2013, researchers with Britain's National Oceanography Centre explored the twilight zone near Ireland from top to bottom, measuring carbon and ocean life at all points. Now, the scientists think they can finally balance the twilight zone's carbon checkbook. The findings were published today (March 19) in the journal Nature. [Venturing to the Ocean's Twilight Zone]

"We've really increased our confidence of what is going into this zone, and what is coming out of it," said Richard Lampitt, a biological oceanographer at the center in Southampton, England.

Carbon accounting

About a quarter of the planet's carbon goes into the oceans, Lampitt said. Most of this carbon that is absorbed by the ocean later returns to the atmosphere (about 90 percent). The rest is recycled within the twilight zone, and just 1 percent falls to the sea floor.

But the carbon that makes it past the bottom of the twilight zone stays trapped in the depths for millennia. Researchers refer to this long-term exile as the Earth's "biological carbon pump."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This process is responsible for reducing carbon dioxide by about 200 parts per million," before fossil-fuel burning started, Lampitt said. For example, without the biological carbon pump, levels of carbon dioxide would have been closer to 500 parts per million (ppm) instead of 280 ppm about 200 years ago, studies suggest. In 2013, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels crossed 400 parts per million (ppm), a million-year high. (Parts per million denotes the volume of a gas in the air; in this case, for every 1 million air molecules, 400 are carbon dioxide.)

Understanding how carbon sinks through the twilight zone and ends up stored in the deep ocean will help researchers improve climate models and understand the balance of the planet's carbon cycle.

The first place that carbon moves from the atmosphere into the ocean is at its sun-warmed surface, where microscopic floating plants called phytoplankton consume carbon dioxide for energy (just like grass and trees). When phytoplankton die, they sink into the twilight zone. These decaying plants are joined by falling particles of flesh, soot and sand — a constant deluge called marine snow. Carbon arrives in the twilight zone via this marine snow.

In the Porcupine Abyssal Plain, about 350 miles (560 kilometers) southwest of Ireland, Lampitt and his colleagues collected marine snow and the creatures that consume it at different depths. They also measured how different organisms use carbon — transforming it into carbon dioxide — rather than just eating the particles, Lampitt said.

"It's very important to draw the distinction between burning up carbon, actually using it by transforming it from organic into inorganic matter, and just eating it," he said.

A poop partnership

The study provides the first balanced carbon cycle for the twilight zone — researchers now know how much carbon goes into the twilight zone, which creatures consume it, and how much comes out. The results also reveal that twilight zone bacteria and zooplankton have a special synergy that plays a prominent role in how much carbon reaches the deep ocean.

"What's being lost at the bottom is entirely determined by the processes within the twilight zone," Lampitt told Live Science.

Here in the gloaming, bacteria and zooplankton scavenge the decaying particles snowing down from the ocean's surface. It turns out that plankton poo is a key player. The zooplankton grabs the fast-sinking particle snow, which are falling too fast for the bacteria to consume. Once the zooplankton poop out their feast, the bacteria get to work, transforming organic carbon into carbon dioxide.

"If it wasn't for the zooplankton chewing them up and defecating, the bacteria wouldn't be able to get their hands on it," Lampitt said. "And most of the work is actually done by the bacteria."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.