A remarkably preserved, 180-million-year-old fossilized fern has been unearthed in Sweden.

The fern was in such pristine condition that its tiny cellular parts were intact, according to a study detailed today (March 20) in the journal Science.

And it turns out, not much has changed for the family of ferns in the last 180 million years.

"The genome size of these reputed living fossils has remained unchanged over at least 180 million years — a paramount example of evolutionary stasis," the authors wrote in the paper. [See Images of the Well-Preserved Fossilized Fern]

Ferns are some of the most primeval plants; they first appeared in the fossil record nearly 360 million years ago. But many modern ferns got their start in the Cretaceous Period, when flowering plants emerged.

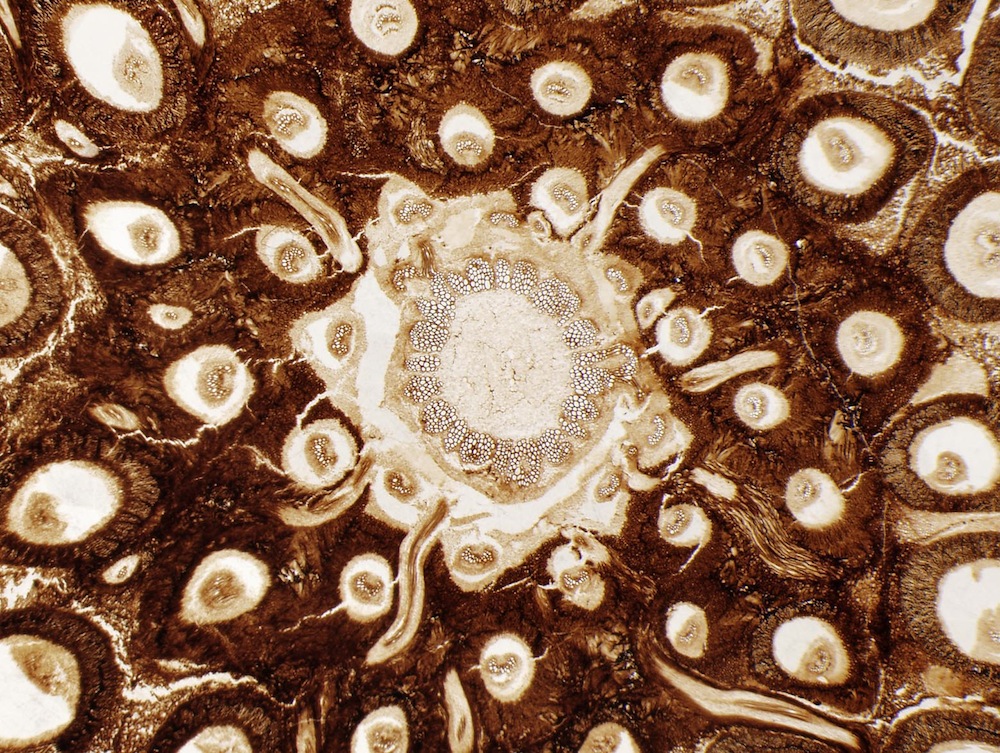

The newfound Jurassic Period fossil fern was uncovered in Korsaröd, Sweden, in a bed of volcanic rock. The specimen, which measures 2.3 inches (5.8 centimeters) long and 1.6 inches (4.1 cm) wide, was so exquisitely preserved that its cytoplasm (the gel-like substance that fills a cell), nuclei and chromosomes were still intact and visible under a microscope. The plant cells were in different stages of cell division.

The fossilized plant was likely preserved when minerals in the superheated, salty water oozing from a crack in the earth, called a hydrothermal brine seep, rapidly crystallized, freezing the plant in time while it was still alive.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By measuring the delicate subcellular parts, the team found the nuclei of the ancient plants were virtually the same size as those in a modern living relative, Osmundastrum cinnamomeum, or the cinnamon fern. The number of chromosomes and the DNA content also seemed to match closely with the modern fern.

The findings suggest this ancient fern hasn't lost or gained much genetic material over the last 180 million years, a remarkably long period to go without much evolutionary change, the authors wrote.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.