Earliest Invasive Cancer Found in 3,000-Year-Old Skeleton

A 3,000-year-old skeleton from a conquered territory of ancient Egypt is now the earliest known complete example of a person with malignant cancer spreading from an organ, findings that could help reveal insights on the evolution of the disease, researchers say.

Cancer is one of the world's leading causes of death today, with numbers more than doubling over the past 30 years. However, direct evidence of cancer from ancient human remains is very rare compared with that from other medical conditions. This suggests the disease could mainly be a product of modern factors such as smoking, diet, pollution and greater life expectancies.

To better understand the apparent rising prevalence of cancer over time, scientists want to investigate signs of cancer in ancient humans. Past research had often discovered evidence of tumors in skeletons — but they were benign ones that lacked the ability to invade neighboring tissues.

However, until now, there were just three tentative examples of malignant tumors predating 1000 B.C. — cancers that can metastasize, or spread to distant parts of the body. (Most people who die of cancer nowadays do so when it metastasizes, as tumors are typically more treatable before they spread.)

Now scientists have found the oldest known complete example of a human skeleton with metastatic cancer — remains unearthed in a tomb in northern Sudan in northeastern Africa. [See Photos of the Ancient Skeleton and Cancerous Tumors]

"The most important implication is that cancer did affect people in the past, too," study lead author Michaela Binder, a bioarchaeologist at Durham University in England, told Live Science. "People have suspected that but again there is very little proof for that."

The skeleton was discovered at the archaeological site of Amara West, located on the left bank of the Nile River, about 465 miles (750 kilometers) downstream of Sudan's modern capital of Khartoum. Aside from a narrow strip of shrubs and trees on the riverbank, the area is now largely desert.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers said the skeleton belonged to a man they estimated was between 25 and 35 years old when he died. He was buried on his back with a faded blue-glazed ceramic amulet in what is now a badly deteriorated painted wooden coffin, alongside 20 other people, perhaps his family.

Life in ancient Nubia

The ancient settlement at Amara West "was founded around 1300 B.C. as the new administrative capital of Kush, the province of Upper Nubia, which was occupied by the ancient Egyptian empire between 1500 B.C. to 1100 B.C.," said Binder, who excavated and examined the skeleton in 2013. Pottery recovered from the skeleton's tomb suggests it dates to the 20th Dynasty of ancient Egypt, or about 1187 to 1064 B.C., when Egypt had conflicts with Libya and while pharaohs such as Ramses III were being buried in the Valley of the Kings. [In Photos: The Mummy of King Ramses III]

Archaeologists are investigating the site because "many questions about the time period of Egyptian occupation of Nubia are still open — most importantly, what was it like to live in occupied Nubia," Binder explained. She said that Amara West is incredibly well-preserved, permitting "a very rare opportunity to not only draw a really comprehensive picture of what life in ancient Nubia was like, but also how it changed over time," Binder said.

At this site, local Nubian peoples lived according to Egyptian standards. For instance, the architecture of this skeleton's tomb is evidence of a hybrid blend of Egyptian elements such as painted coffins and burial gifts alongside Nubian elements such as a low mound to mark the tomb.

"From footprints left on wet mud floors to the healed fractures of many ancient inhabitants, Amara West offers a unique insight into what it was like to live there — and die — in Egyptian-ruled Upper Nubia 3,200 years ago," study co-author and project director Neal Spencer at the British Museum said in a statement.

The main hazard of working at Amara West "are the nimiti, small black flies that are a pest that usually befalls the area between January and March for about six weeks," Binder said. "They produce painful bites; on bad days, we can only work covered in mosquito nets. There are also quite a lot of crocodiles in the area; we see them from the boat when we go back from [the] site around lunch time, but they usually don't attack people."

Still, "the work at Amara West was one of the least difficult and most enjoyable research projects I've ever worked on," Binder said. "We live on a small island of about 300 inhabitants near the site in a traditional Nubian mud brick house amidst a group of other vividly colored Nubian houses. The people are exceptionally friendly."

Ancient bone lesions

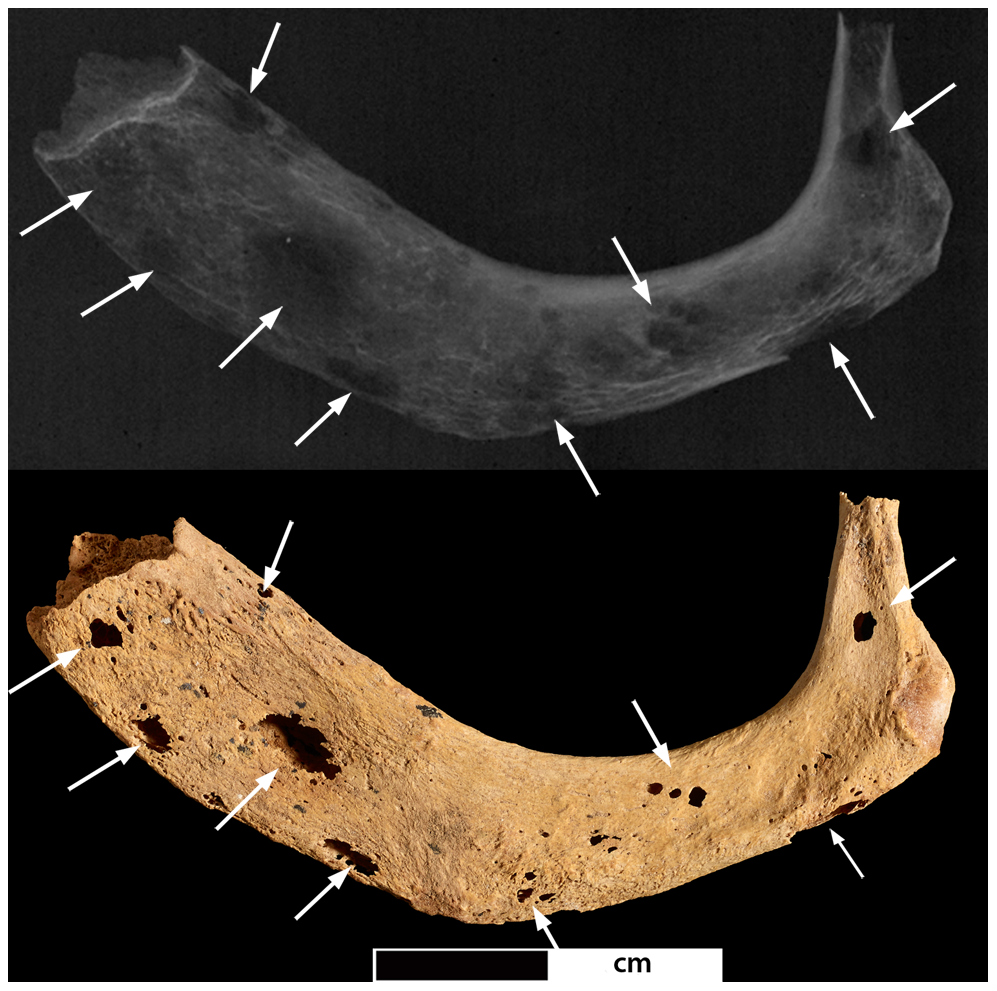

To examine the skeleton, researchers used X-rays and a scanning electron microscope. They developed clear images of lesions on the bones, evidence of metastases on the collar bones, shoulder blades, upper arms, vertebrae, ribs, pelvis and thigh bones. They suspect these resulted from cells that spread from a tumor in a soft organ. [Image Gallery: Ancient Corpse Reveals Medical Oddity]

"This is the oldest complete skeleton with this particular type of cancer — bone metastases spreading from cancer in an organ," Binder said.

The scientists can only speculate on what caused this cancer. They suggest it could be the result of genetic factors, or environmental carcinogens such as smoke from wood fires, or infectious diseasessuch as schistosomiasis, which is caused by parasites. Schistosomiasis plagued inhabitants of Egypt and Nubia since at least 1500 B.C., and is now recognized as a cause of bladder and breast cancers in men.

Future research could help pinpoint the cause of this ancient cancer by analyzing this body's DNA to look for the mutations that might be to blame for the disease.

"What is important about such pre-modern findings in humans is the fact that they can help us understand what factors lead to cancer before the onset of modern living conditions," Binder said. "It could be possible to see if and how the human genomechanged and what factors made us susceptible to cancer. Together with a sound historical background we could then also understand what factors led to these changes. This could help predict developments in the future and may be useful for medical research in developing new ways of research or therapies."

Unfortunately, DNA is not always preserved, so it is possible such research would not be successful, Binder said. Another problem scientists in Sudan face is the increasing destruction of sites there.

"At Amara it is currently a race against time, because on one hand there is increasing looting by real tomb robbers — we had two large chamber tombs completely destroyed between the seasons 2013 and 2014 — and on the other hand there are plans to build new dams along the Nile. One of them, if it's going to be built, would entirely destroy the cemeteries of Amara West," Binder said.

The scientists detailed their findings online March 17 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.