Humans to Blame for Giant Bird's Extinction

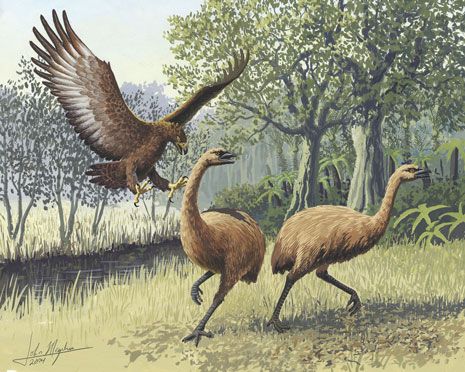

Fossils are all that's left of the giant wingless birds called moa that once roamed New Zealand. These big-bodied megaherbivores, some of them weighing up to 550 pounds (250 kilograms), disappeared soon after Polynesians colonized the islands in the late 13th century.

Some researchers had argued the nine species of moa were already in decline by the time humans entered the scene. Others had proposed the birds' population collapsed in the wake of volcanic eruptions or the spread of diseases, before they ever met Homo sapiens. A new study, however, suggests humans are responsible for the birds' demise.

"Elsewhere the situation may be more complex, but in the case of New Zealand the evidence provided by ancient DNA is now clear: The megafaunal extinctions were the result of human factors," Mike Bunce, a professor at Curtin University in Australia, said in a statement. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

By looking at the genetic profiles of 281 individual fossil specimens, Bunce and colleagues pieced together the demographic trends across four different species of moa during the 5,000 years leading up to their extinction. They say they found no genetic signatures of decline.

On the contrary, genetic diversity remained consistent and the moa gene pools were "extremely stable throughout their last 5,000 years," said Morten Allentoft, who was a doctoral student in Bunce's lab.

One species, the South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus), even seemed to be experiencing a population boom with as many as 9,200 individuals roaming about by the time Polynesians landed on New Zealand's shores.

"If anything it looks like their populations were increasing and viable when humans arrived," Allentoft said in a statement. "Then they just disappeared."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Archaeological evidence shows that moa were hunted voraciously and vanished just one or two centuries after humans showed up in New Zealand. In addition to overhunting, other indirect human impacts could have contributed to the moa's quick decline, including fires and the introduction of invasive species.

Bunce believes there are lessons to be learned from the moa's extinction.

"As a community we need to be more aware of the impacts we are having on the environment today and what we, as a species, are responsible for in the past," Bunce said.

The research was detailed this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.