Missing Half of Bone Reveals Prehistoric Sea Giant

At first, Gregory Harpel thought the dark-brown object he found was just a stone. But it was oddly placed, resting in an isolated spot on a grassy embankment along a creek in Monmouth County, N.J. A closer look confirmed he had found something much more interesting.

"I started seeing the little holes in the bone that the blood vessels go through," said Harpel, an amateur fossil hunter who made this discovery in 2012. "I thought maybe it was a dinosaur of some sort."

The fossil didn't turn out to be from a dinosaur. But thanks to a number of coincidences, Harpel had just made an unprecedented discovery that would reveal the existence of an ancient ocean giant. [See Photos of the Newly Discovered Giant's Bones]

Half a humerus

At the New Jersey State Museum, David Parris, curator of natural history, was able to identify the mystery object: It was the lower half of an upper forelimb bone of a sea turtle that lived at the same time as the dinosaurs. Parris remembered looking at another broken sea-turtle forelimb bone in a collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia.

"He said offhandedly, 'Maybe we ought to take it to the Academy [of Natural Sciences] and see if it fits," said Jason Schein, the assistant natural history curator at the New Jersey State Museum. "Dave was half joking, thinking that could never, ever happen."

Even so, Schein brought Harpel's bone to the Academy. They put the two pieces of fossilized bone together, and aside from a few chips around the edge of the break, they fit perfectly. Harpel's half would have attached to the turtle's elbow, while the Academy's half would have attached to its shoulder, forming a complete bone known as the humerus.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The history behind the Academy's piece of bone makes this story even more extraordinary. It's not clear when or how the 202-year-old Academy acquired the fossil, but the first scientific description of it in 1849 identified it as belonging to an ancient sea turtle. This means the first half of this sea-turtle fossil was discovered at least 163 years, and most likely more, before Harpel found the second half. [6 Strange Species Discovered in Museums]

"Unfortunately, things were not as well documented in those days," said Ted Daeschler, associate curator of vertebrate zoology at the Academy.

The first half of a humerus offered enough information that the species to which it belonged could be named Atlantochelys mortoni. For more than 160 years, it remained the only piece of this turtle ever found.

An unprecedented discovery

Paleontologists can sometimes return to the site where a specimen was removed and find other fossils missed by the earlier excavation. And pieces of museum specimens can be misplaced and then rediscovered many years later. "But no one has ever found another part of a single bone 163 years apart," Schein said. "To say this is a once-in-a-lifetime experience is shortchanging it, because it has never happened before."

The paleontologists think the bone was buried in one piece and then broke in two when it eroded from its original burial. Reunited, these halves tell paleontologists more about the turtle to which they belonged. "It turns out to be an amazing animal," Daeschler said.

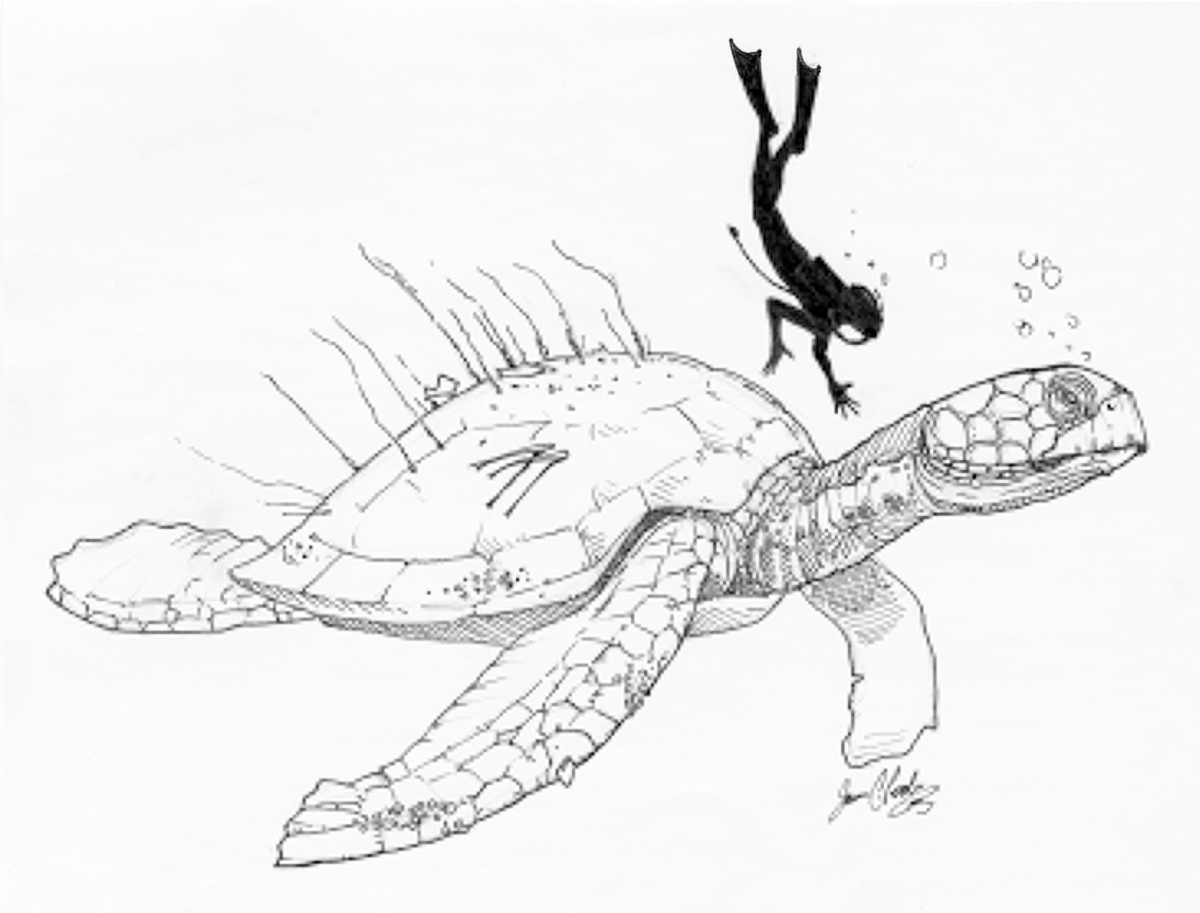

Based on the size of the full humerus, the researchers can estimate the size of the turtle, which they put at about 3 meters (9.8 feet) from nose to tail. That makes the animal among the largest sea turtles ever to have lived. The loggerhead turtle appears to be its closest living relative, he said.

Because of the lack of records for the Academy's half of the fossil, paleontologists had no idea what rock formation produced it. Harpel's discovery made it possible for them to pinpoint the Mount Laurel Formation, which was deposited below a shallow sea, in which sharks and now-extinct marine reptiles called mosasaurs also swam, about 75 million years ago.

"It's all part of painting a picture of the past," Daeschler said. "I think those are the really important scientific discoveries here."

The researchers describe the discovery in the 2014 issue of the journal Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.