After a long stretch of pedal-to-the-metal driving, NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has its next science target in sight.

The 1-ton Curiosity rover is just 282 feet (86 meters) north of a site called "the Kimberley," where four different types of terrain intersect. The rover's handlers are keen to study the Kimberley rocks and may even break out Curiosity's sample-collecting drill at the site, NASA officials said.

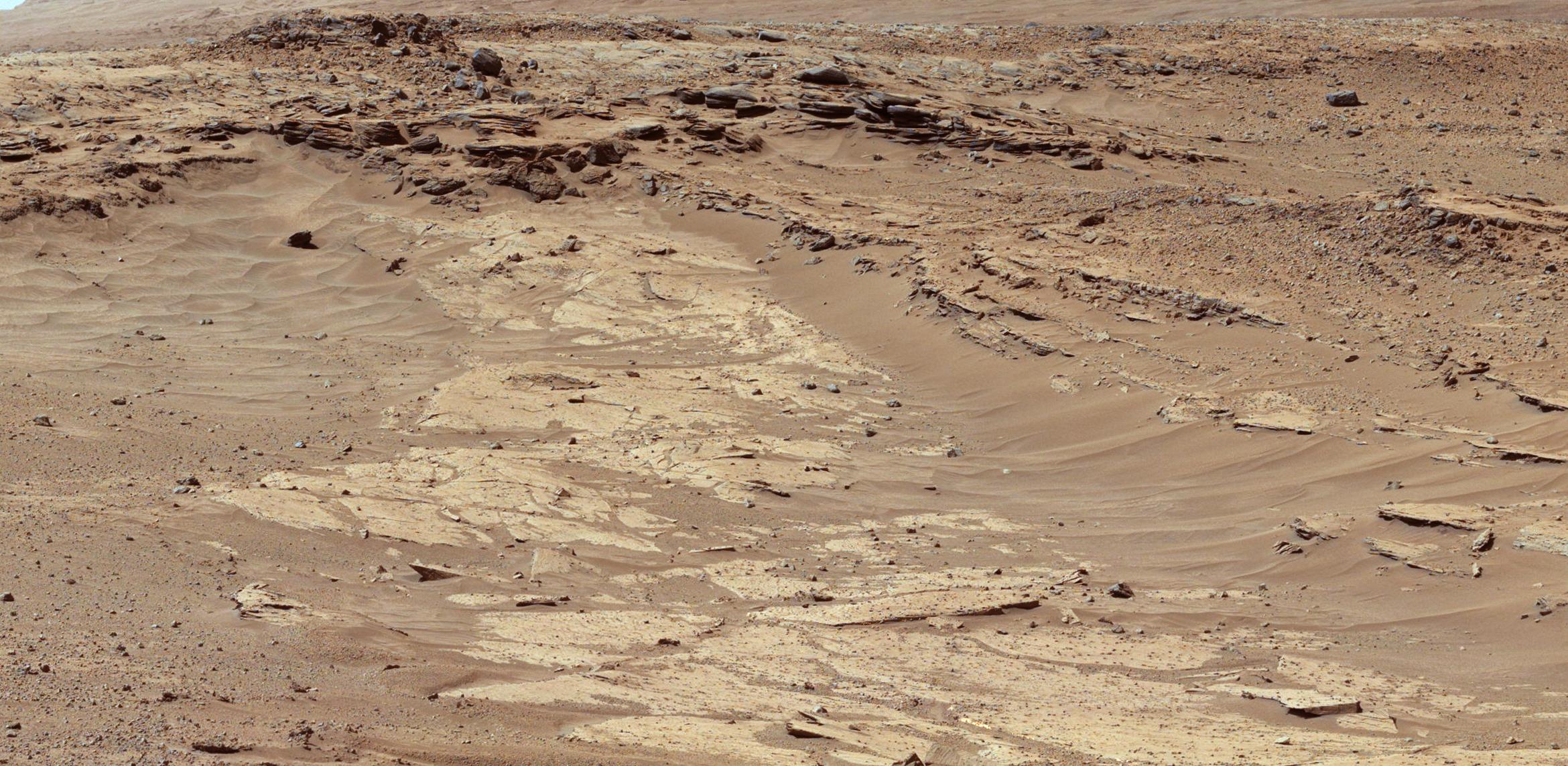

"The orbital images didn't tell us what those rocks are, but now that Curiosity is getting closer, we're seeing a preview," Curiosity deputy project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. [Latest Amazing Photos From the Curiosity Rover]

"The contrasting textures and durabilities of sandstones in this area are fascinating," Vasavada added. "While superficially similar, the rocks likely formed and evolved quite differently from each other."

The Kimberley sandstones represent a different type of rock for Curiosity to examine. Since touching down inside Mars' huge Gale Crater in August 2012, the rover has primarily scrutinized finer-grained mudstones, researchers said.

Some of those mudstones, at a site called Yellowknife Bay, preserved evidence of an ancient stream-and-lake system, leading mission scientists to announce last year that Mars could have supported microbial life billions of years ago.

Understanding variations in Martian sandstones — such as why some are harder than others — could help scientists piece together parts of the Red Planet's past and explain the large-scale contours of Gale Crater, researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"A major issue for us now is to understand why some rocks resist erosion more than other rocks, epecially when they are so close to each other and are both likely to be sandstones," said Michael Malin, of Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego. Malin is the principal investigator for Curiosity's Mast Camera and Mars Descent Camera.

Curiosity is currently en route to the base of Mount Sharp, which rises 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers) into the sky from Gale Crater's center. The rover's handlers want Curiosity to climb up Mount Sharp's foothills, reading a history of Mars' changing environmental conditions as it goes.

Curiosity left the Yellowknife Bay area last July. While the six-wheeled robot has stopped occasionally since then to examine rocks, the mission team has mainly prioritized making tracks. The road to Mount Sharp covers more than 5 miles (8 km); Curiosity should get there around the middle of this year, officials have said.

The long journey has been hard on Curiosity's metal wheels, spurring the rover team devise ways to minimize wear and tear. Their strategies — which include driving Curiosity backward for stretches and choosing a less punishing route — appear to be paying off, with the wheel-puncture rate dropping to just 10 percent of what it was a few months ago.

"The wheel damage rate appears to have leveled off, thanks to a combination of route selection and careful driving," said JPL's Richard Rainen, mechanical engineering team leader for Curiosity. "We're optimistic that we're doing OK now, though we know there will be challenging terrain to cross in the future."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.