Nearing Collapse? West Antarctica's Glaciers Speeding Up

Six big glaciers in West Antarctica are flowing much faster than 40 years ago, a new study finds. The brisk clip may mean this part of Antarctica, which could raise global sea level by 4 feet (1.2 meters) if it completely melts, is nearing full-scale collapse.

"This region is out of balance," said Jeremie Mouginot, lead study author and a glaciologist at University of California, Irvine. "We're not seeing anything that could stop the retreat of the grounding line and the acceleration of these glaciers," he told Live Science. (A grounding line is the location where the glacier leaves bedrock and meets the ocean.)

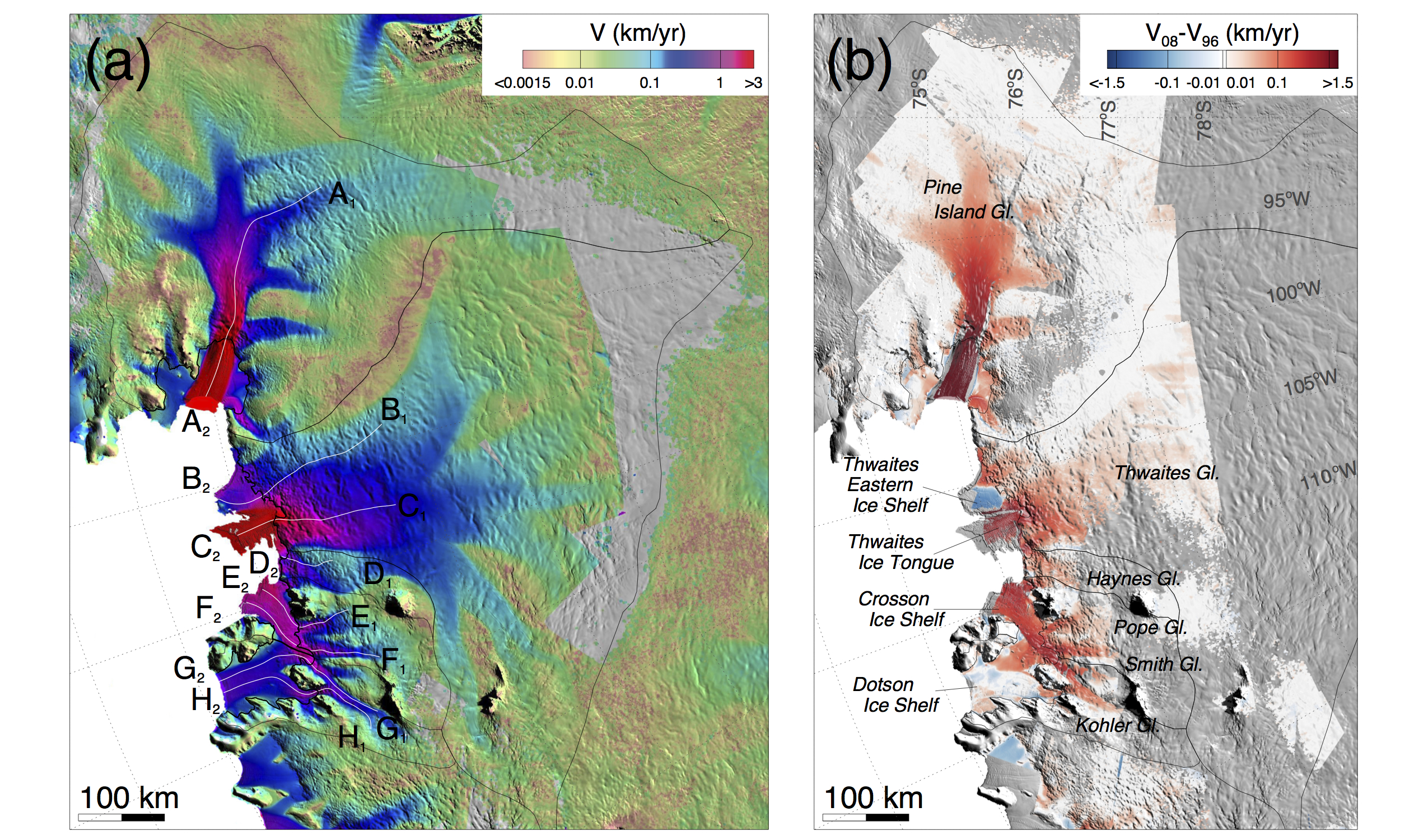

From satellite observations such as Landsat images and radar interferometry, Mouginot and his co-authors tracked the speed of West Antarctica's six largest glaciers. The biggest of the half-dozen are Pine Island Glacier, known for cleaving massive icebergs, and its neighbor, Thwaites Glacier. The other four are Haynes, Smith, Pope and Kohler glaciers. [Video: Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier Is Rifting]

Ice from the six glaciers accounts for almost 10 percent of the world’s sea-level rise per year. Researchers worry the "collapse" of West Antarctica's glaciers would hasten sea-level rise. The collapse refers to an unstoppable, self-sustaining retreat that would drop millions of tons of ice into the sea.

The amount of ice draining from the six glaciers increased by 77 percent between 1973 to 2013, the study found. However, the race to the sea is happening at different rates. Recently, the fast-flowing Pine Island Glacier stabilized, slowing down starting in 2009. (The slowdown was only at the ice shelf, where the glacier meets the sea. Further inland, the glacier is still accelerating.)

But Pine Island Glacier's sluggishness was matched by an increase at Thwaites Glacier starting in 2006, the researchers found. For the first time since measurements began in 1973, Thwaites starting accelerating. Thwaites quickened its pace by 0.5 miles (0.8 kilometers) per year between 2006 and 2013, the study found.

"To see Thwaites, this monster glacier, start accelerating in 2006 means we could see even more change in the near future that could affect sea level," Mouginot said. The acceleration extends far inland for both Pine Island Glacier and Thwaites Glacier, he said. Pine Island Glacier's acceleration reached up to 155 miles (230 km) inland from where it meets the ocean.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mouginot said warmer ocean waters contributed to the speed up. The huge ice streams flowing from West Antarctica are held back by floating ice shelves that act like dams. Several recent studies have suggested that warmer ocean water near Antarctica is melting and thinning these ice shelves from below. The thinner ice shelves offer less resistance, making it easier for glaciers to bulldoze their way toward the sea.

"This region is considered the potential leak point for Antarctica because of the low seabed. The only thing holding it in is the ice shelf," said Robert Thomas, a glaciologist at the NASA Wallops Flight Facility, in Wallops Island, Va., who was not involved in the study.

The study was published March 5 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.