What is normal blood sugar?

Maintaining a healthy blood glucose range is important, but what is normal blood sugar?

Blood sugar, or glucose, is the main source of fuel for our bodies. It powers up our internal organs, muscles and nervous system. Keeping your blood sugar in check is essential to our physical health, wellbeing and energy levels. But what is considered a normal blood glucose level? And what happens when it rises above the normal threshold?

Our blood sugar levels are directly related to the food we eat. We obtain glucose mostly from carbohydrate-rich foods like bread, pasta, potatoes or fruit, but many different food groups play a role in regulating glucose metabolism. How we absorb, use and store this important sugar is dependent on multiple complex processes that take place in our digestive systems.

There is no single universal value that would describe a healthy blood sugar level. What constitutes normal blood glucose varies for an individual depending on a range of factors, including age, any underlying medical conditions, and the medications they take. It will also be heavily linked to when you consumed your last meal. Hence when we refer to 'normal blood sugar levels', we refer to a range of values that are considered healthy.

Here, we will discuss everything you need to know about a healthy blood sugar range.

Normal blood sugar before and after meals

Normal blood sugar levels vary from person to person. That's why when we talk about 'normal' blood glucose levels, we refer to a range of values that are considered healthy for most individuals. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a normal range for fasting blood sugar (the amount of glucose in your blood at least eight hours after a meal) is between 70 and 100 milligrams per deciliter (mg/DL).

For most people, eating a meal or drinking a sugary drink will lead to a temporary increase in the blood glucose levels. As stated by the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the blood sugar two hours after eating should not exceed 140 milligrams per deciliter. However, people with certain metabolic conditions, such as prediabetes or diabetes, typically have lower blood sugar than those guidelines suggest. Researchers from the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology continuously measured people's blood glucose and found that most individuals averaged around 82 mg/DL during the night and around 93 mg/DL during the day, and spiked to a maximum of 132 mg/DL an hour after a meal.

Fluctuations in blood glucose levels, both before and after meals, are perfectly normal and reflect how your body absorbs, uses and stores this important sugar at a given point in time. When your food reaches your stomach, your digestive enzymes will break down complex carbohydrate molecules into smaller particles - sugars such as glucose. Glucose is then absorbed by the small intestine and eventually passed into the bloodstream, where it's distributed across the body. In order for the glucose to be shepherded into the cells and utilised, the pancreas needs to release the hormone insulin.

Our bodies are designed to keep glucose levels constant in the blood. After all the energy needed is delivered to the body's cells, any leftover glucose needs to be stored away. It can't be stored in its original form, it needs to be transformed into a compound called glycogen. Glycogen then is built into the liver and the muscles as a backup source of energy if blood glucose levels fall below optimum levels.

When there isn't enough glucose stored to maintain normal blood-sugar levels, the body can also produce its own glucose from non-carbohydrate sources (such as amino acids and glycerol). This process is known as gluconeogenesis and occurs most often during intense exercise or starvation. It's also common when following low-carb diets, such as keto or Atkins.

While it may seem complicated (and it is), there's a good reason for our bodies to keep up this never-ending dance with glucose: too much or too little glucose in the blood can lead to serious health problems.

When there is too much glucose over an extended time (hyperglycemia), it can lead to severe nerve damage, impaired immunity, and heart and kidney disease.

On the other hand, not enough glucose in the blood over several minutes to hours (hypoglycemia) can negatively affect the functioning of the nervous system. Common symptoms of hypoglycemia include fatigue, fainting, irritability and, in some cases, seizures, coma and death.

Blood sugar targets in people with diabetes

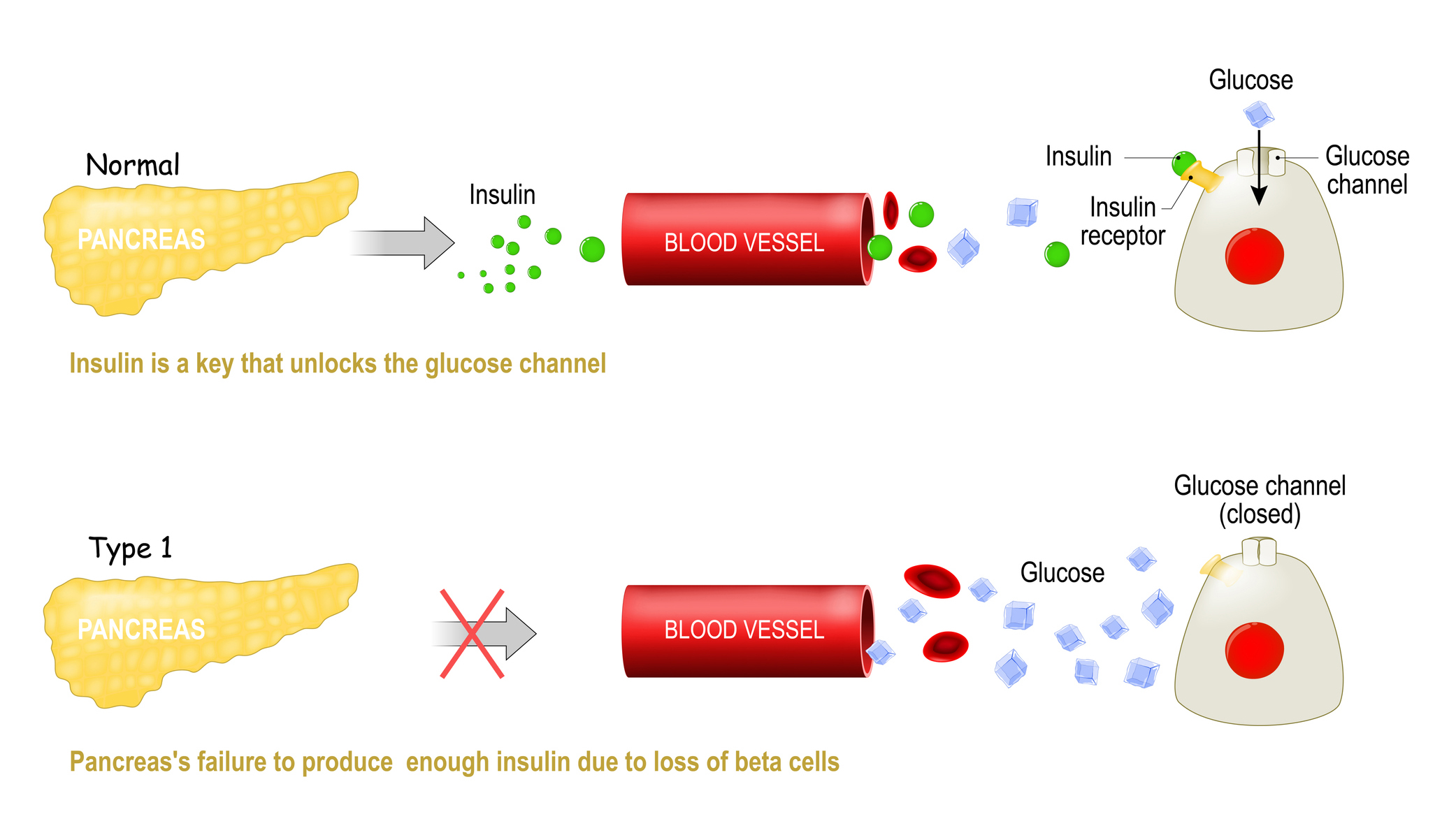

In people with diabetes, blood sugar levels are too high, either because the individual isn't making any insulin (type 1 diabetes), or isn't able to make or use insulin efficiently (type 2 diabetes). As a result, glucose levels then remain elevated in the blood and fuel can't enter cells.

Blood sugar targets for diabetes patients are based on how long the person has had diabetes for, their age, and other underlying medical conditions and lifestyle factors.

But generally, according to the ADA, for most non-pregnant adults with diabetes the fasting blood sugar target range should be in the range of between 80 and 130 mg/DL. Meanwhile, the ADA suggests the after-meal goal about two hours after eating for the same subset of patients should be less than 180 mg/DL.

Overall, eating plenty of fruit and vegetables, maintaining a healthy weight, and getting regular physical activity alongside medication can all help stabilize and maintain normal blood sugar levels in people with type 2 diabetes.

For pregnant women who have pre-existing diabetes or develop diabetes during pregnancy, ADA guidelines are generally lower. Fasting glucose targets for this population should be less than 95 mg/DL, while they suggest that the after-meal goal about two hours after eating should be below 120 mg/DL.

- Related: Type 3 diabetes: Symptoms, causes and treatments

- Related: Vegan diet for diabetes: Tips, benefits and safety

What is a normal A1C?

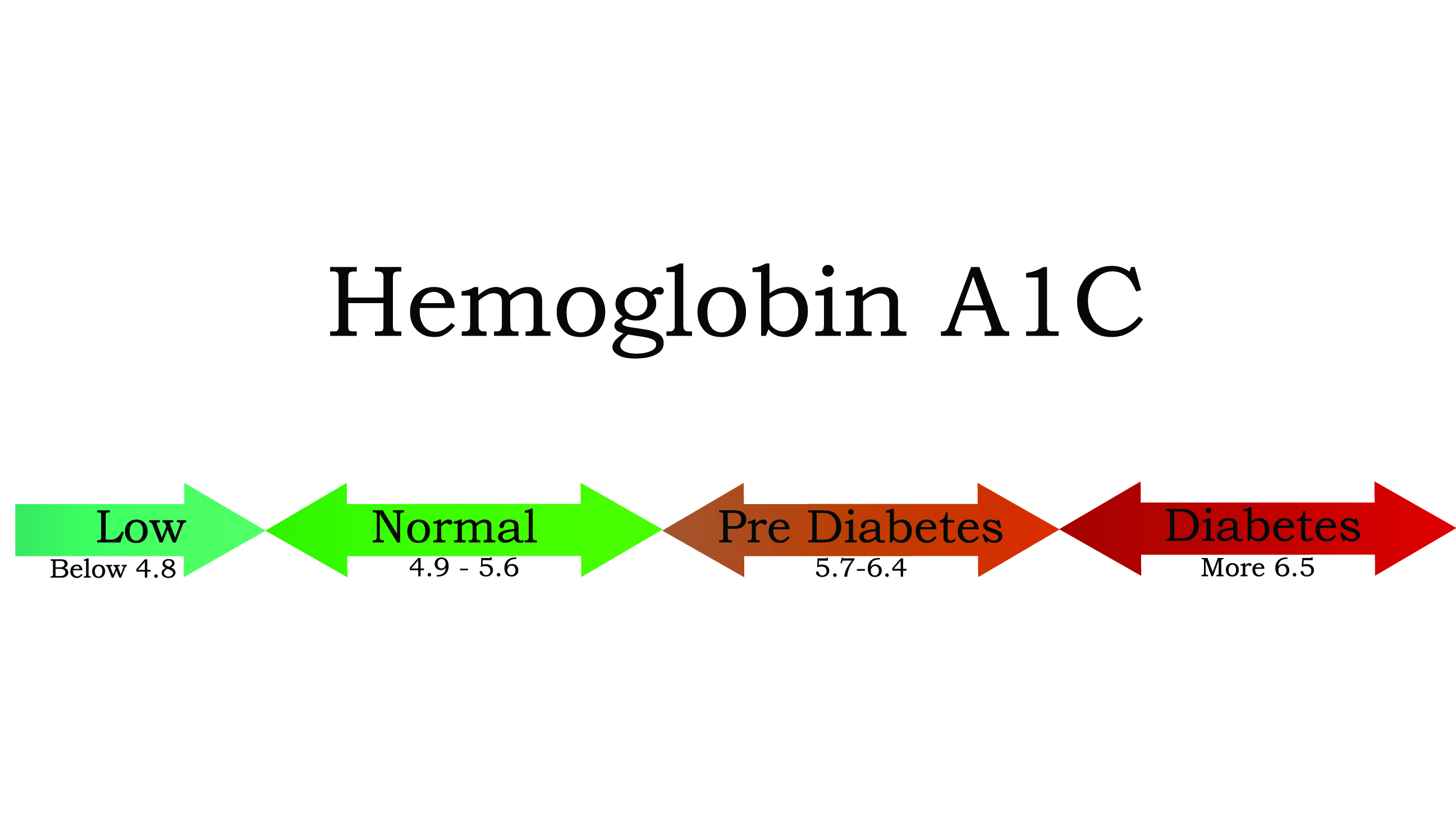

A person's A1C is a measure of their average blood glucose levels over the previous 2 or 3 months, and it is measured through a blood test. A normal result for someone without diabetes or prediabetes would be below 5.7%; an A1C between 5.7% and 6.4% indicates prediabetes; and if your A1C is above 6.4% you would be diagnosed as having diabetes, according to the CDC.

Specifically, the A1C test is a measure of the percent of your red blood cells that have sugar-coated hemoglobin attached to them. The glucose that enters your bloodstream (from carbohydrates that you eat) gets stuck to hemoglobin molecules on red blood cells. And the more glucose in your bloodstream (higher blood sugar levels), the more of your blood's hemoglobin will be "sugar-coated," and the higher your A1C will be, according to the CDC. As such, for people with diabetes (type 1 or 2), the number can give you and your doctors a sense of how well your sugars are being controlled.

The ADA recommends that most adults with diabetes should keep their A1C below 7% to reduce the risk of diabetes-related complications; the goal is the generally the same for many children with diabetes Targets for the elderly with diabetes are slightly less stringent — for the otherwise healthy with few coexisting chronic illnesses and intact cognitive function, the ADA recommends less than 7.5%, while those who don't meet these requirements have a more lenient goal of below 8.0% to 8.5%.

According to the Mayo Clinic, higher A1C numbers are linked to a greater risk for diabetes complications, while lower A1Cs have been correlated with a reduced risk of these complications, such as heart disease, kidney disease and vision problems.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is not meant to offer medical advice.

This article was updated on Aug. 24, 2022 by Live Science Health Writer Anna Gora.

Additional resources

- Learn more about how high blood sugar levels put you on the road to developing diabetes and heart disease in this explainer by Harvard Health.

- Read about the risk of high sugar levels and diabetes in pregnant women in this explainer by the Cleveland Clinic.

- Discover the dangers of low blood sugar, with or without diabetes, in this explainer by the Mayo Clinic.

Bibliography

"The Big Picture: Checking Your Blood Sugar," American Diabetes Association. https://www.diabetes.org/healthy-living/medication-treatments/blood-glucose-testing-and-control/checking-your-blood-sugar

"Mean fasting blood glucose." World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/2380

"Continuous Glucose Profiles in Healthy Subjects under Everyday Life Conditions and after Different Meals" 2017, Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2769652/

"Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021." ADA. https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/44/Supplement_1/S200/30761/14-Management-of-Diabetes-in-Pregnancy-Standards

"Diabetes tests." CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/getting-tested.html

"Understanding A1C." ADA. https://www.diabetes.org/a1c

"Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021." ADA. https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/44/Supplement_1/S168/30583/12-Older-Adults-Standards-of-Medical-Care-in

"A1C test." Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/a1c-test/about/pac-20384643

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Natalie Grover is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering all things health and science. She spent her formative years as a journalist with Reuters, writing about the business of health. Based in London, UK, she has a masters degree in medicine, health and public policy, and is working on making her coverage statistically significant. In her free time, she monitors her wildly fluctuating heartbeat whilst watching Arsenal FC (and enjoys long walks on the beach). Most days she can be found at the gym and aiming to feed her family healthy food.