The Saturn moon Enceladus harbors a big ocean of liquid water beneath its icy crust that may be capable of supporting life as we know it, a new study reports.

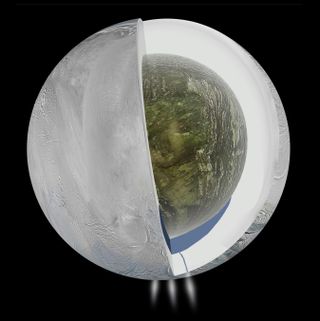

The water ocean on Enceladus is about 6 miles (10 kilometers) deep and lies beneath a shell of ice 19 to 25 miles (30 to 40 km) thick, researchers said. Further, it's in direct contact with a rocky seafloor, theoretically making possible all kinds of complex chemical reactions — such as, perhaps, the kind that led to the rise of life on Earth.

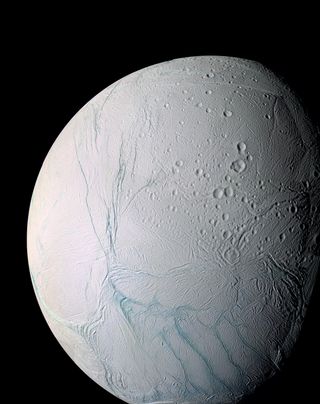

"The main implication is that there are potentially habitable environments in the solar system in places which are completely unexpected," study lead author Luciano Iess said in a video about the discovery produced by his home institution, Sapienza University in Rome. "Enceladus has a surface temperature of about minus 180 degrees Celsius [minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit], but under that surface there is liquid water." [Photos: Enceladus, Saturn's Cold, Bright Moon]

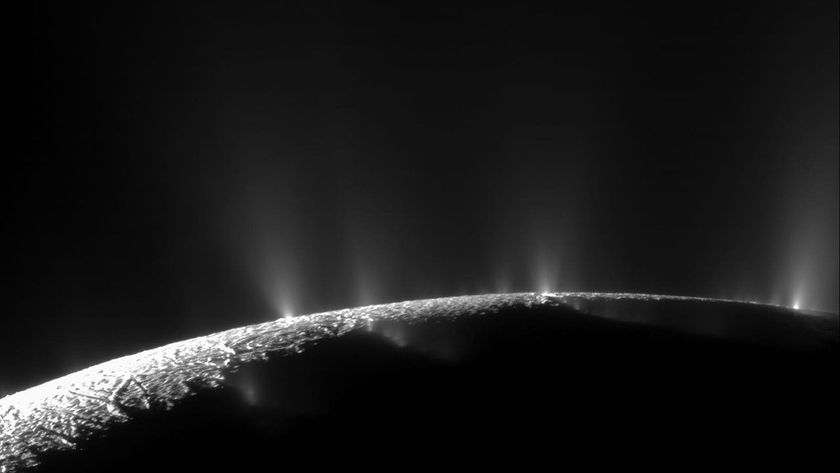

The new finding, which is published online today (April 3) in the journal Science, doesn't exactly come out of left field. Rather, it confirms suspicions many researchers have had about Enceladus since 2005, when NASA's Cassini spacecraft first spotted ice and water vapor spewing from fractures near the moon's south pole.

Measuring Enceladus' gravity

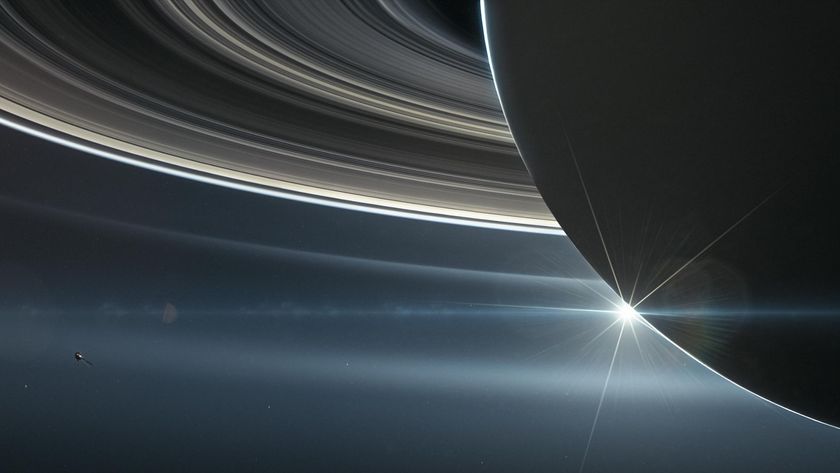

Iess and his colleagues mapped out Enceladus' gravity by measuring how the 313-mile-wide (504 km) moon tugged on Cassini during three close flybys from 2010 to 2012.

"As the spacecraft flies by Enceladus, its velocity is perturbed by an amount that depends on variations in the gravity field that we're trying to measure," co-author Sami Asmar, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. "We see the change in velocity as a change in radio frequency, received at our ground stations here all the way across the solar system."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This ultra-precise tracking system — NASA's Deep Space Network can tell if Cassini speeds up or slows down by just 1 foot (0.3 meters) per hour — revealed the presence of a "negative mass anomaly" at Enceladus' south pole. In other words, the area harbors less mass than would be expected for a perfectly spherical body.

That makes sense, because a large depression marks the south pole's surface,researchers said. But the observed mass anomaly is significantly smaller than expected based on the size of the dent (about 0.6 miles, or 1 km deep).

The researchers thus concluded that "extra" mass underground must be reducing the effect. A subsurface ocean of liquid water, which is denser than ice, is the only reasonable candidate, they said.

The heat required to keep this water in a liquid state is generated within Enceladus, with much of that energy perhaps coming from tidal interactions between Enceladus and another of Saturn's moons, Dione. The moon's internal energy stores are prodigious; a 2011 study found that Enceladus' south polar region pumps out 15.8 gigawatts of heat-generated power, equivalent to the output of 20 coal-fired power plants.

A lot of water

The team's calculations suggest that the moon's ocean covers at least as much area as Lake Superior, the second-largest lake on Earth — though the icy moon's sea is much deeper than Lake Superior and thus holds a great deal more water.

The ocean is likely confined to the moon's southern hemisphere, reaching halfway to the equator or so from the pole. But the study team cannot rule out the possibility that it extends globally, said co-author Dave Stevenson of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

The subsurface sea probably feeds Enceladus' geysers, which blast organic compounds — the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it — into space along with ice and water vapor. [Enceladus' Surprising Geysers (Video)]

Further, the new study marks the first time scientists have used gravity measurements to discover an ocean on another world, Stevenson said. For example, researchers inferred the existence of a subsurface sea on Jupiter's moon Europa from magnetic-field data, which indicated the presence of an underground conductive layer (almost certainly salty water).

Water on rock

The gravity measurements also suggest that Enceladus is composed of layers of different materials, with a low-density core consisting of silicate rock underlying the ocean, researchers said.

![[Pin It] Enceladus's water vapor jets, emitted from the southern polar region.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/XuQXHVUwLbuJ2dXFyCC2SL-320-80.jpg)

This is good news for anyone hoping that life may have sprung up on the frigid Saturn satellite.

"When you have a situation like this, where the ocean is sitting next to the rock, there's a greater likelihood of some interesting chemistry," Stevenson said.

Europa's sea similarly abuts rock, while some other satellites — such as Jupiter's huge moon Ganymede — appear to have subsurface seas that touch only ice above and below, he added.

Indeed, the similarities between Europa and Enceladus continue to mount. Late last year, for example, researchers announced the discovery of water-vapor plumes erupting from Europa's south polar region.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.