Ancient Egyptian Mummy Found With Brain, No Heart

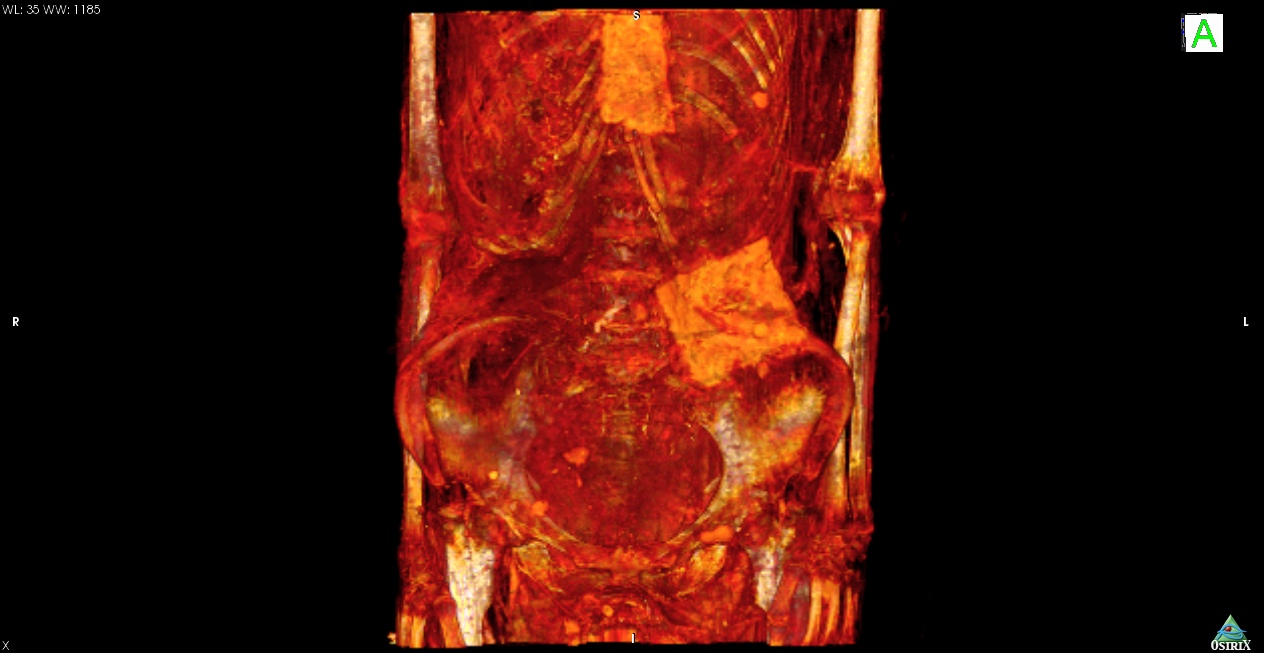

An ancient Egyptian mummy found with an intact brain, but no heart, has a plaque on her abdomen that may have been intended to ritually heal her, say a team of researchers who examined the female body with CT scans.

The woman probably lived around 1,700 years ago, at a time when Egypt was under Roman rule and Christianity was spreading, according to radiocarbon dating. Her name is unknown and she died between age 30 and 50. Like many Egyptians, she had terrible dental problems and had lost many of her teeth.

The use of mummification was in decline as Roman culture and Christianity took hold in the country. But this woman and her family, apparently strong in their traditional Egyptian beliefs, insisted on having the procedure done. [See Images of the Ancient Egyptian Mummy & Weird Plaque]

To remove her organs, the scans show, the embalmers created a hole through her perineum and removed her intestines, stomach, liver and even her heart. Her brain, however, was left intact. Spices and lichen were spread over her head and abdomen, and she was wrapped and presumably put in a coffin; her final resting place was likely near Luxor, 19th century records say.

Before the embalmers were finished they filled the hole in the perineum with linen and resin. They also put two thin plaques similar to cartonnage (a plastered material) on her skin above her sternum and abdomen, something that may have been intended to ritually heal the damage the embalmers had done and act as a replacement, of sorts, for her removed heart.

"The power of current medical imaging technologies to provide evidence of change in ancient Egyptian mortuary ritual cannot be understated," writes the research team in an article to be published in the "Yearbook of Mummy Studies." While the technology is powerful it does have some limits. The presence of spices and lichen on the head were first found in the 19th century when the head was unwrapped. The CT scans revealed that they are likely also located on the mummy's abdomen, a determination aided by this unwrapping.

The mummy and its coffin — now at the Redpath Museum at McGill University in Montreal — were purchased at Luxor in the 19th century. Scientists aren't sure if the coffin she is in now was originally meant for her. Antiquity dealers in the 19th century would sometimes place a mummy into a coffin from another tomb to earn more money. Coffins were also sometimes reused in antiquity.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What happened to the heart?

The heart played a central role in ancient Egyptian religion, being weighed against the feather of ma'at (an Egyptian concept that included truth and justice) to see if one was worthy of entering the afterlife. For this reason, Egyptologists had long assumed the Egyptians didn't remove that organ, something that recent research into several mummies, including this one, contradicts. [See Images of the Egyptian Mummification Process]

With evidence showing the heart was removed on at least some occasions Egyptologists are left with a question, what did the ancient Egyptians do with it?

"We don't really know what's happening to the hearts that are removed," said Andrew Wade, a professor at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada, in an interview with Live Science. During some time periods, the hearts may have been put in canopic jars, a type of jar used to hold internal organs, though tissue analysis is needed to confirm this idea, Wade said.

Healing the mummy?

Even more mysterious is a question that Wade's team is currently grappling with: Why did this woman receive two plaques in areas that were never sliced open?

The plaque on the sternum may have acted as a replacement, of sorts, for the removed heart, they said. However, the one on the abdomen is more ambiguous. The team knows that mummies who were dissected through the abdomen received a plaque like this, however, scans reveal this woman's abdomen was never touched.

The embalmers may have thought the plaque would help by ritually healing the hole they had created in the woman's perineum, the researchers speculate. By doing so they may have been trying to give her "a more favorable afterlife, healed and protected as she was by the embalmer's additional efforts," the researchers write in their paper.

In addition to the current study, another paper presenting informationabout the mummy was published in 2012 in the journal RSNA RadioGraphics, and a reconstruction of the mummy's face by forensic artist Victoria Lywood was released last year.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.