Drone Images Reveal Buried Ancient Village in New Mexico

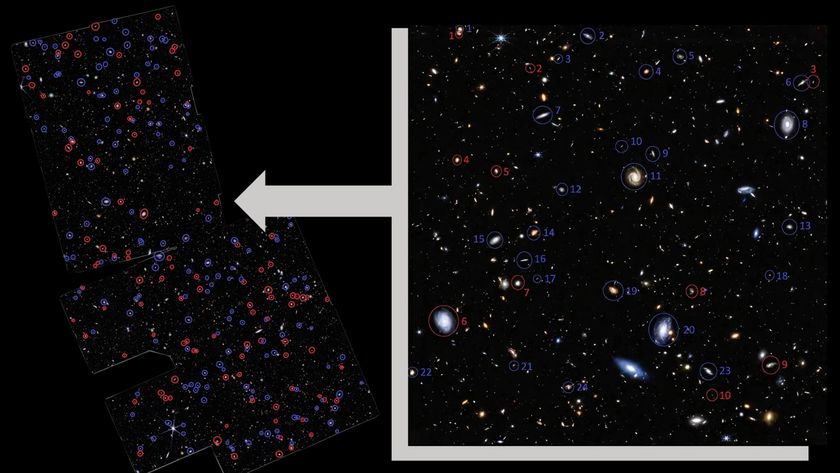

Thermal images captured by a small drone allowed archaeologists to peer under the surface of the New Mexican desert floor, revealing never-before-seen structures in an ancient Native American settlement.

Called Blue J, this 1,000-year-old village was first identified by archaeologists in the 1970s. It sits about 43 miles (70 kilometers) south of the famed Chaco Canyon site in northwestern New Mexico and contains nearly 60 ancestral Puebloan houses around what was once a large spring.

Now, the ruins of Blue J are obscured by vegetation and buried in eroded sandstone blown in from nearby cliffs. The ancient structures have been only partially studied through excavations. Last June, a team of archaeologists flew a small camera-equipped drone over the site to find out what infrared images might reveal under the surface. [Chaco Canyon Photos: The Center of an Ancient World]

"I was really pleased with the results," said Jesse Casana, an archaeologist from the University of Arkansas. "This work illustrates the very important role that UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) have for scientific research."

Casana said his co-author, John Kantner of the University of North Florida, had previously excavated at the site and the drone images showed stone compounds Kantner had already identified and ones that he didn't know about.

For example, the thermal images revealed a dark circle just inside the wall of a plaza area, which could represent wetter, cooler soil filling a kiva, or a huge, underground structure circular that would have been used for public gatherings and ceremonies. Finding a kiva at Blue J would be significant; the site has been considered unusual among its neighbors because it lacks the monumental great houses and subterranean kivas that are the hallmark of Chaco-era Pueblo sites, the authors wrote in the May issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The images also could guide archaeologists' trowels before they ever break ground.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Now that we know what household compounds look like in thermal imaging, we could use it to prospect for structures at other sites," Casana told Live Science.

How it works

Archaeological features like bricks and stone walls retain and emit warmth differently than the surrounding soil, meaning heat maps can provide an outline of rubble buried underground. Casana said archaeologists have been talking about using thermal imaging technology to probe ancient sites for decades, but it's been almost impossible to operationalize.

"To do it, you need to get a really high-resolution thermal image collected at the right time of day," Casana said. "It involves tasking a plane with a very expensive sensor to fly at a very low altitude, and that’s just not something that archaeologists could afford."

Casana primarily studies archaeology of the Middle East and was leading a dig in Syria until civil war broke out in the country in 2011. In 2012, he got a Start-Up grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities to study aerial thermographic imaging. Casana has been investigating archaeological sites with an eight-rotor CineStar 8 remote-controlled copter, which he built from a $6,000 kit a few years ago. So far, he has tested the technology at a site in Cyprus, a Plains Village settlement in South Dakota and the ancient city of Cahokia near modern-day St. Louis, among others. He said he would be taking the craft to Iraq this summer for a new project in Kurdistan.

The uncertain future of drones for science

Archaeologists and other scientists who want to study the Earth from above are increasingly looking at drones as a research tool as the cost for unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, goes down. But the technology is hardly perfect, and there are legal hurdles, too.

"People who fly them for fun say it's not a question of if you'll crash it, but when and how badly," Casana said. He found that to be true in his trials. Hardware sometimes comes loose mid-flight and the software on the ground occasionally freezes, Casana said. He travels with replacement parts and backup systems like balloons and kites.

Meanwhile, the lack of regulations for UAVs in the United States makes it difficult to implement the technology just yet.

The Federal Aviation Administration has set a goal to implement commercial drone regulations by 2015 and recently designated six drone-testing centers across the country to research how UAVs could be safely introduced to U.S. skies. FAA officials have held that it is illegal to fly commercial drones until they write those rules, though they suffered a setback last month when a judge for the National Transportation Safety Board overturned the FAA's decision to fine a man $10,000 for using a drone to shoot a promotional video, Bloomberg News reported.

To comply with these legal gray areas, Casana said he had to rely student volunteers to operate the drone in New Mexico this summer. ("Hobbyists" have no problem flying the aircraft.) He expressed concern that debates about drone use often ignore scientific applications.

"When legislators think about use of technology, they often don't think about science," Casana said. "They need to come up with some regulations. Until they do, it's really kind of hamstringing science."

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.