Parasitic Amoeba Chomps on Human Cells to Kill Them

Amoebae — a group of amorphous, single-celled organisms that live in the human body — can kill human cells by biting off chunks of intestinal cells until they die, a new study finds.

This is the first time scientists have seen this method of cell killing, and the new findings could one day help treat parasitic infections that kill children across the globe, the researchers said.

Investigators analyzed the amoeba Entamoeba histolytica. This parasite causes amoebiasis, a sometimes-fatal diarrheal disease seen in the developing world. Amoebiasis is also a problem in the developed world — for instance, among travelers and immigrants. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

"Diarrhea is more important as a cause of child death than malaria, tuberculosis or HIV," said study author William Petri, chief of the division of infectious diseases and international health at the University of Virginia. In the slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh, for instance, one-third of all children are infected with the parasite by their first birthday, he said.

This amoeba "can slice through the gut, causing colitis, or inflammation of the colon, and spread to the liver to cause liver abscesses," Petri said. "However, it was a mystery for 111 years, since Entamoeba histolytica was first named, as to how it kills cells," he added.

Scientists had suggested the amoebae kill cells before devouring them. However, the researchers now show the reverse happens: The amoebae nibble on cells to kill them.

The discovery was made by the study's lead author, Katherine Ralston, a cell biologist at the University of Virginia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It was completely surprising," Petri told Live Science. "It was an observation Katy [Ralston] made that I had missed, and I've studied this parasite for my entire professional career — 25 years on the faculty."

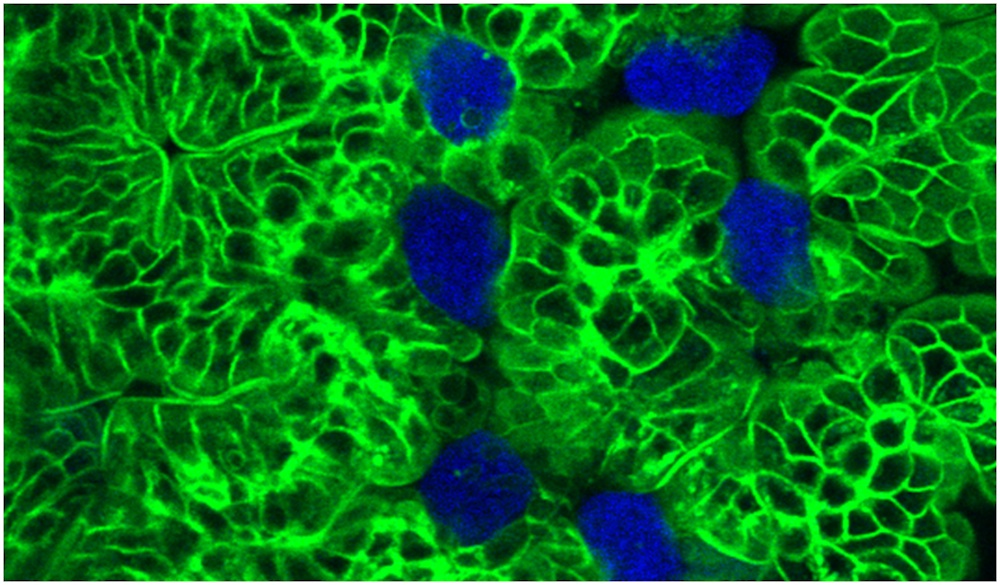

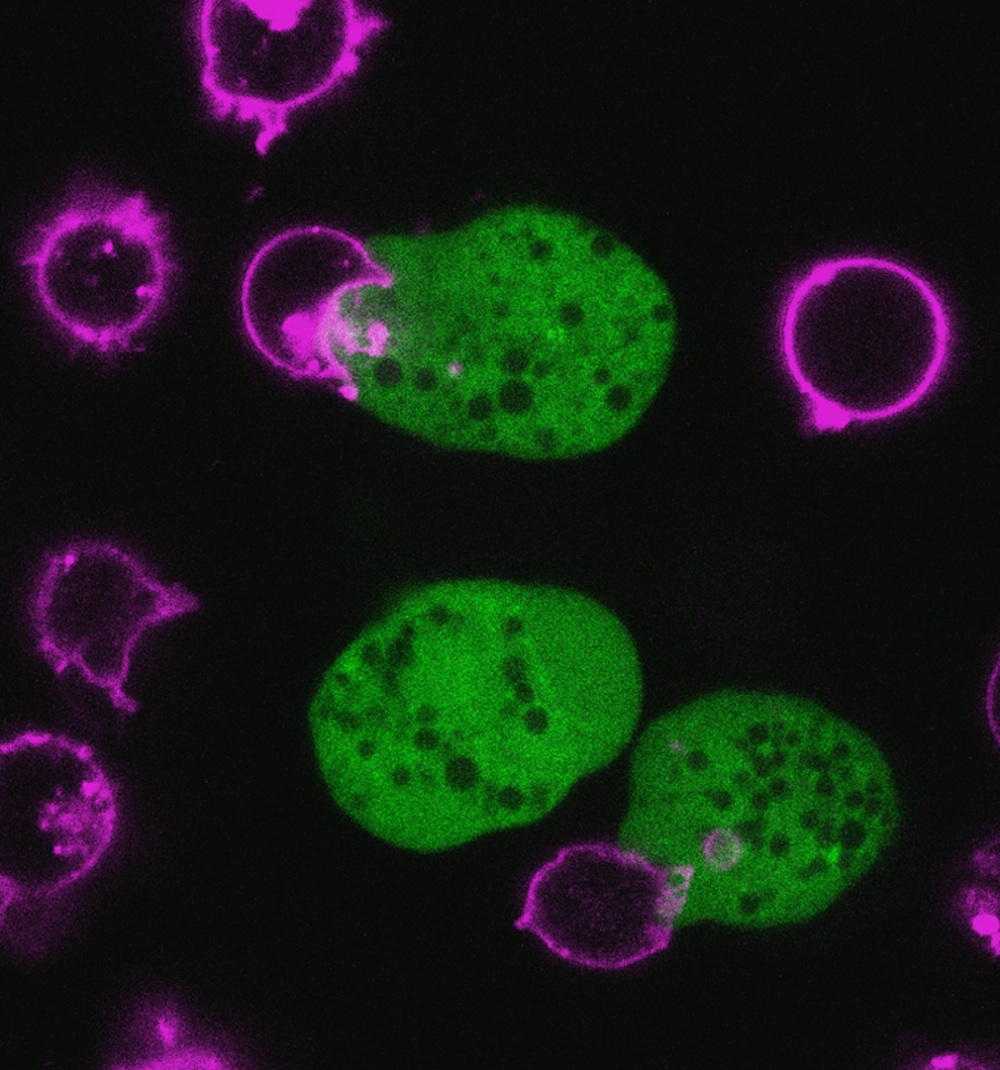

Through microscopic observations, Ralston had seen hints that these amoebae were nibbling cells to death. She confirmed these findings by labeling human cells with fluorescent tags and seeing tiny, glowing bits of those cells end up within the parasites.

Single bites did not kill cells. Rather, it took many bites for cells to die, the researchers said.

This nibbling is similar to a process called trogocytosis, which is nibbling that has previously been seen by cells of the immune system. However, immune trogocytosis does not kill its targets, whereas amoebic trogocytosis does.

"This is a completely novel mechanism of cell killing," Petri said. "It remains to be seen what other organisms and what other biological processes might involve this as well."

Because trogocytosis is seen in both amoebae and humans, this might be evolutionarily ancient, "dating back well before multicellular organisms evolved," Petri said.

Intriguingly, the amoebae likely derive little sustenance from the cells they nibble to death, the researchers said. Moreover, the amoebae do not feed on the corpses of the cells they kill — once the cells are dead, the parasites detach, effectively spitting out the corpses. The amoebae probably live mostly off the hordes of bacteria that normally live in the human gut, the researchers said.

If the amoebae aren't getting significant nutritional value from the cells they bite to death, then why kill them? They could be doing so to evade the human immune system, the researchers suspect.

"Normally, many human cells die in the body every day, and cells known as macrophages eat these dead cells," Petri said. When macrophages eat cells, they usually release chemicals that dampen inflammation. "Maybe, by leaving dead cells around, the amoebae suppress inflammation that might otherwise hurt them," Petri said.

A better understanding of how this amoeba kills cells might lead to ways to prevent or treat amoebiasis, Petri said. For instance, this amoeba uses a unique sugar-binding protein to latch onto cells, and developing vaccines against this protein could help suppress the disease. The scientists also found that drugs that suppressed a protein unique to the amoeba stopped them from munching on the human cells.

"By targeting molecules unique to the parasite, we have a better chance of therapies that combat the amoeba without affecting humans," Petri said.

The scientists detail their findings in the April 10 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.