Bank Hard! Flies Fly Like Fighter Jets to Evade Predators

Catching a fly isn't easy, as anyone who's ever tried to swat one knows. Why are they so hard to catch? It could be because they maneuver like fighter jets, a new study shows.

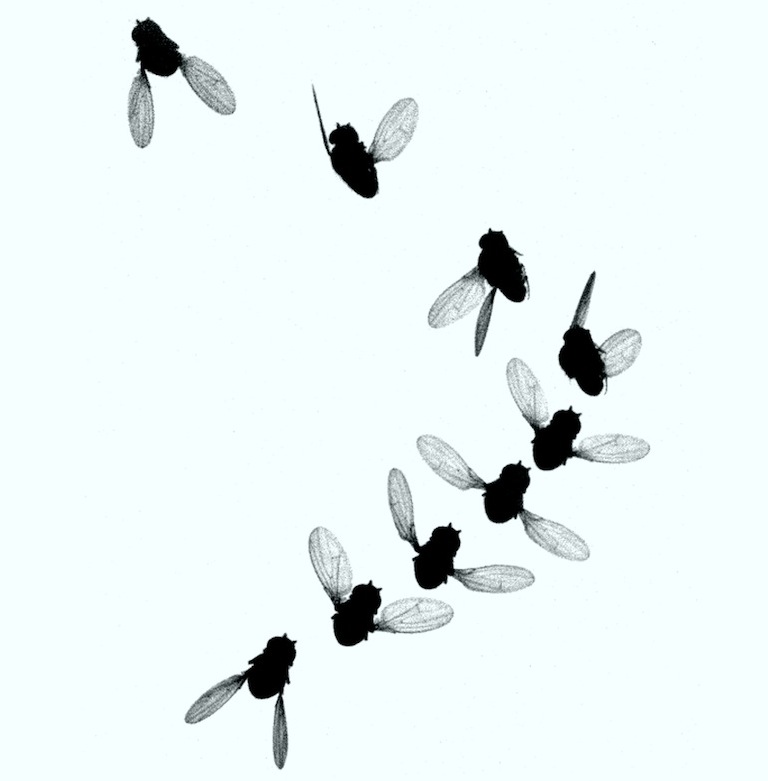

Using high-speed video cameras, a team of researchers captured the lightning-fast wing and body motion of fruit flies as the insects performed rapid, banked turns to avoid a looming threat. The team also used giant, robotic flies to understand how the sprightly pests performed these aerobatics.

The species of fruit flies in the study, Drosophila hydei, is known for its excellent flying ability. Scientists have sometimes compared their flight to "swimming" through the air, but the flies' airborne gymnastics are closer to those of a fighter pilot, the researchers said. [See Video of Flies Flying Like Fighter Jets]

"These flies roll up to 90 degrees — some are almost upside down — to maximize their force, and escape," said study researcher Florian Muijres, who studies the biomechanics of flight and swimming at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The flies can change course in less than 1/100th of a second — 50 times faster than the blink of an eye, the researchers said.

It's a bird, it's a plane…

Muijres and his team took fruit flies, which are about the size of a sesame seed, and put them in an arena where they were free to buzz around. High-speed cameras filming at 7,500 frames per second were focused on the middle of the arena, where two lasers were set up. The cameras require very bright light to function, but regular light would have blinded the flies. So, instead, the team flooded the arena with infrared light (which is invisible to flies and humans).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When a fly flew through the lasers, it triggered an expanding black shadow to appear, resembling a predator or an obstacle, which prompted the fly to take evasive action.

The flies performed amazing feats of agility. As the looming shadow approached, the flies tipped their bodies in screeching midair turns. The insects usually flap their wings 200 times per second, but to avoid the shadow, they were able to change direction with barely more than a single flap, producing a force that propelled them away from the danger.

To execute these movements, the fly's brain must be performing a sophisticated calculation, Muijres said. "The fact that flies roll to the side is maybe not that surprising," he said, but "the surprise is really the accuracy and speed combination."

Fruit flies have tiny brains, yet they are capable of flight maneuvers that are much more complex than those of many other flying insects. For example, moths have larger brains than flies do, but they dive straight into the ground to avoid being caught by bats.

What's more, the fly's behavior "is very fast, and it's completely innate — the fly doesn't need to learn how to do this," said senior study co-author Michael Dickinson, a biologist at the University of Washington. Exactly how the fly's brain executes these stunts is something the researchers plan to investigate in future studies.

RoboFly

To model the flies' flight dynamics, the researchers put a giant robotic fly, with a 2-foot (0.6 meters) wingspan, in a vat of mineral oil. Scientists have used such robot flies, which have names like "RoboFly" of "Bride of RoboFly," for years to study these insects' flight on a much larger scale.

Given this newfound knowledge of fly flight, what's best way to catch a fly?

"From the side," Muijres said, though he hasn't tried it yet.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.