Titanic Sunk During Average Iceberg Year

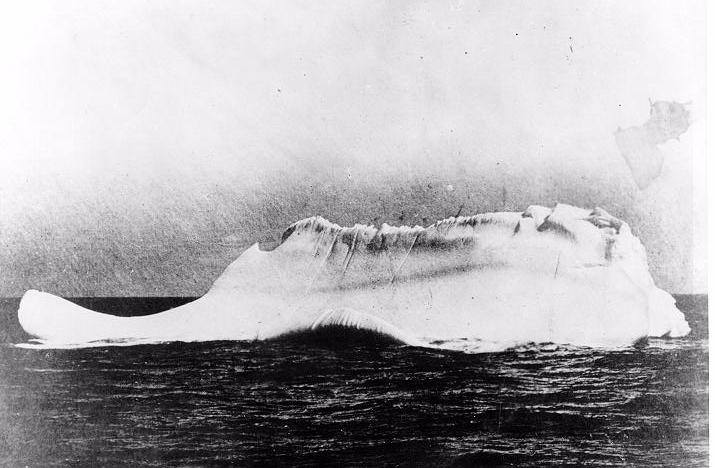

Built in Northern Ireland in 1909, the "RMS Titanic" was also known as the "unsinkable ship," because it had a double-bottom hull divided into 16 compartments that were presumed to be watertight. The 882.5-foot-long (268.9 meters) craft sank in April 1912 after it struck an iceberg off southern Newfoundland, and now rests on the ocean floor at a depth of 12,460 feet (3.7 kilometers). (Image credit: NOAA | Institute for Exploration | University of Rhode Island)

Old Coast Guard records are throwing cold water on a long-standing explanation for the loss of the Titanic: the suggestion that the fateful journey took place in waters bristling with icebergs, making 1912 an unlucky year to sail the North Atlantic.

Instead, more than a century of Atlantic iceberg counts reveals 1912 was an average year for dangerous floating ice. The findings also contradict a popular notion that the Jakobshavn Isbrae glacier on Greenland's west coast birthed the Titanic's deadly 'berg. Instead, a computer model suggests that one of the glaciers at Greenland's southern tip released the iceberg that hit the Titanic on April 14, 1912, drowning more than 1,500 people in the frigid ocean.

"I think the question of whether this was an unusual year has been laid to rest," said Grant Bigg, an environmental scientist at the University of Sheffield and lead study author, adding, "1912 is not an exceptional year."

After a glancing collision with an estimated 325-foot (100 meters) wide iceberg on April 14 of that year, the Titanic broke into two pieces and sank. In the decades since, the tragedy has acquired a vast history and mythology as people seek to account for the loss of the "unsinkable" ship on its maiden voyage.

For example, many Titanic theorists have said that 1912 was an exceptional iceberg year. Explanations for the purported abundance of icebergs have ranged from a warm 1912 winter, to sunspots, to high tides from a 1912 'supermoon,' which could have dislodged icebergs.

But the new findings contradict these earlier theories. "This really refutes the arguments that have been around about things like high tides or sunspots generating excessive numbers of icebergs in that year," Bigg told Live Science. [Video: How the Titanic Sank]

The research was published today (April 10) in the journal Weather.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Floating floes

The new results come from a broader examination of Greenland icebergs by Bigg and study co-author David Wilton, also from the University of Sheffield. The researchers are tracking icebergs over time to test Greenland's response to climate change and the contribution to sea level rise from icebergs. They are studying data collected by the U.S. Coast Guard's International Ice Patrol extending back to 1900.

According to Bigg, 1912 was a high ice year, but not exceptional compared with the surrounding decades.

In 1912, data shows that 1,038 icebergs moved south from Arctic waters, and crossed the 48th parallel. The Coast Guard records show a slightly higher number of 1,041 icebergs crossed south of 48 degrees north in 1909. Between 1901 and 1920, five years saw at least 700 icebergs drift below 48 degrees north, where they could menace ships.

Bigg said the broader study indicates climate change has increased the risk of icebergs for ships sailing near Greenland in recent decades. Between 1991 and 2000, five years saw more icebergs below the 48th parallel than in 1912. "The values are now twice as high as the largest values from earlier in the century," Bigg said. "Greenland's contribution to sea level rise is increasing."

Birth of a tragedy

Bigg and Wilton also created a computer model to plot the likely path of icebergs discharged from Greenland's glaciers. The model showed that the deadly 1912 iceberg probably originated from southern Greenland in late summer or early autumn of 1911. This 'berg likely sailed directly southwest toward southern Labrador and Newfoundland, rather than heading north up the Greenland coast into Baffin Bay and circling around via the Labrador Current, as other models have suggested, Bigg said.

The iceberg was originally 1,640 feet (500 m) wide and 985 feet (300 m) high, the model indicates. By April, the floating chunk was just 325-foot (100 meters) wide.

"It still looked large to the people on the ship, but it had melted quite a bit," Bigg said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science..