Raining Frogs & Fish: A Whirlwind of Theories

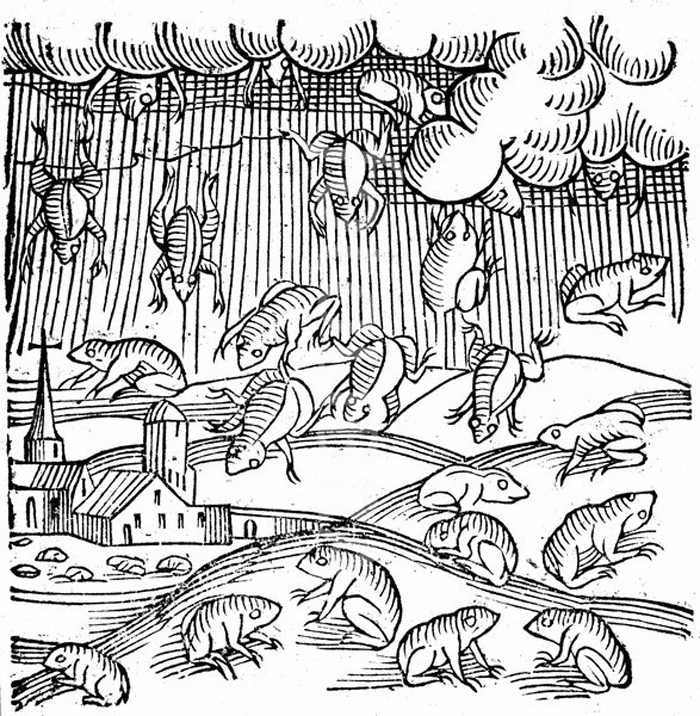

For millennia, people have reported a rare and strange phenomenon: a sudden rain of frogs — or fish or worms — from the sky. You may be minding your own business walking in a park on a blustery day when a small frog hits you on the top of the head. As you peer down at the stunned animal, another one comes down, and another and another all around you, in a surreal rain of frogs in various states of trauma.

Charles Fort, an early collector of reports about strange phenomena, noted the following in his 1919 tome, "The Book of the Damned": "A shower of frogs which darkened the air and covered the ground for a long distance is the reported result of a recent rainstorm at Kansas City, Mo." This report first appeared in the July 12, 1873, issue of Scientific American. Fort noted dozens of similar reports from around the world and wrote that as "for accounts of small frogs, or toads, said to have been seen to fall from the sky, [a skeptical] writer says that all observers were mistaken: that the frogs or toads must have fallen from trees or other places overhead."

Any number of small animals have been reported falling from the sky, including ants, small fish and worms. Modern examples tend to be rare, but reports do surface occasionally in magazines devoted to strange phenomenon such as Fortean Times (named after Fort). Frog rains were mentioned in an episode of "The X-Files" titled "Die Hand Die Verletzt" ("The Hand That Wounds"), in which Agent Scully exclaims, "Mulder... toads just fell from the sky," to which the unflappable Agent Mulder replies, "I guess their parachutes didn't open."

Bob Rickard and John Michell, in their book, "The Rough Guide to the Unexplained," note that "The quality of the evidence for rains of fishes and frogs is good, with a canon of well-observed cases going back to antiquity." According to Jane Goldman's "The Book of The X-Files," "Falls of animals were first recorded in A.D. 77, in Pliny's 'Natural History' which scoffed at the idea that they could rain from the skies, suggesting instead that they grew from the ground after heavy rains."

This explanation likely seemed reasonable 2,000 years ago — after all, some animals such as worms and insects do seem to suddenly "appear" on the grounds during and following heavy rains, driven to the surface because they cannot breathe in the soaked soil. So if the frogs don't originally come from the skies, and they don't "grow" out of the ground after being watered, where do they come from? [Pictures: Cute and Colorful Frogs]

Explanations?

The most likely explanation for how small frogs get up into the sky in the first place is meteorological: a whirlwind, tornado or other natural phenomenon. Fort admitted that this is a possibility, but offered several reasons why he doubted that's the true or complete explanation: "It is so easy to say that small frogs that have fallen from the sky had been scooped up by a whirlwind ... but [this explanation offers] no regard for mud, debris from the bottom of a pond, floating vegetation, loose things from the shores — but a precise picking out of the frogs only. ... Also, a pond going up would be quite as interesting as frogs coming down. Whirlwinds we read of over and over — but where and what whirlwind? It seems to me that anybody who had lost a pond would be heard from." For example, Fort argued, one published report of "a fall of small frogs near Birmingham, England, June 30, 1892, is attributed to a specific whirlwind — but not a word as to any special pond that had contributed."

What about the reasons that Fort and others cite for why a whirlwind is not a good explanation? Frogs and fish do not of course live in the sky, nor do they suddenly and mysteriously appear there; in fact they share a common habitat: ponds and streams. It's certain that they gained altitude in a natural, not supernatural, way. [Countdown: Fishy Rain to Fire Whirlwinds: The World's Weirdest Weather]

That there are very few eyewitness accounts of frogs and fish being sucked up into the sky during a tornado, whirlwind or storm is hardly mysterious or unexplainable. Anytime winds are powerful enough to suck up fish, frogs, leaves, dirt and detritus, they are powerful enough to be of concern to potential eyewitnesses. In other words, people who would be close enough to a whirlwind or tornado to see the flying amphibians would be more concerned for their own safety (and that of others) to pay much attention to whether or not some frogs are among the stuff being picked up and flown around at high speeds. These storms are loud, windy, chaotic, and hardly ideal for accurate eyewitness reporting.

The same applies to Fort's apparent surprise that, following frog falls, farmers or others don't come forward to identify which specific pond the frogs came from. How would anyone know? Whirlwinds and tornadoes may move quickly and over many miles, destroying and lifting myriad debris in its wake. Unless a farmer took an inventory of all the little frogs in a pond both before and after a storm, there's no way anyone would know exactly where they came from, nor would it be noteworthy.

Of course, a wind disturbance need not be a full-fledged tornado to be strong enough to pick up small frogs and fish; smaller, localized versions such as waterspouts and dust devils — which may not be big enough, potentially damaging enough, or near enough to populated areas to be reported in the local news — may do the trick.

High winds, whirlwinds and tornadoes are strong enough to overturn cars and rip the roofs off of buildings. In 2012, a 2-year-old Indiana girl was lifted into the air during a storm, and, incredibly, carried into the sky and found alive 10 miles away. Strong winds are certainly powerful enough to lift up and carry frogs into the air. It is, of course, possible that there is some unknown, small-frog-levitating force at work in nature, but until and unless that is verified, it seems likely that this mystery is solved after all.

Benjamin Radford, M.Ed, is a member of the American Folklore Society and author of seven books including Scientific Paranormal Investigation: How to Solve Unexplained Mysteries. His Web site is www.BenjaminRadford.com.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality