Body Slam This! Ancient Wrestling Match Was Fixed

Who says only modern-day pro wrestling is fake?

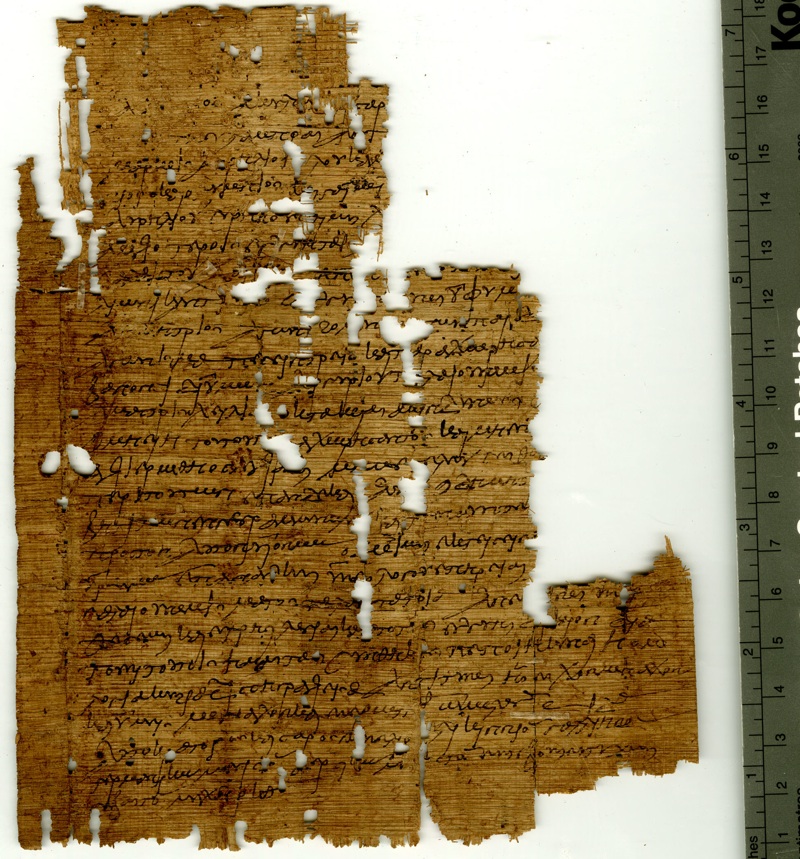

Researchers have deciphered a Greek document that shows an ancient wrestling match was fixed. The document, which has a date on it that corresponds to the year A.D. 267, is a contract between two teenagers who had reached the final bout of a prestigious series of games in Egypt.

This is the first time that a written contract between two athletes to fix a match has been found from the ancient world.

In the contract, the father of a wrestler named Nicantinous agrees to pay a bribe to the guarantors (likely the trainers) of another wrestler named Demetrius. Both wrestlers were set to compete in the final wrestling match of the 138th Great Antinoeia, an important series of regional games held along with a religious festival in Antinopolis, in Egypt. They were in the boys' division, which was generally reserved for teenagers. [In Photos: Gladiators of the Roman Empire]

The contract stipulates that Demetrius "when competing in the competition for the boy [wrestlers], to fall three times and yield," and in return would receive "three thousand eight hundred drachmas of silver of old coinage …"

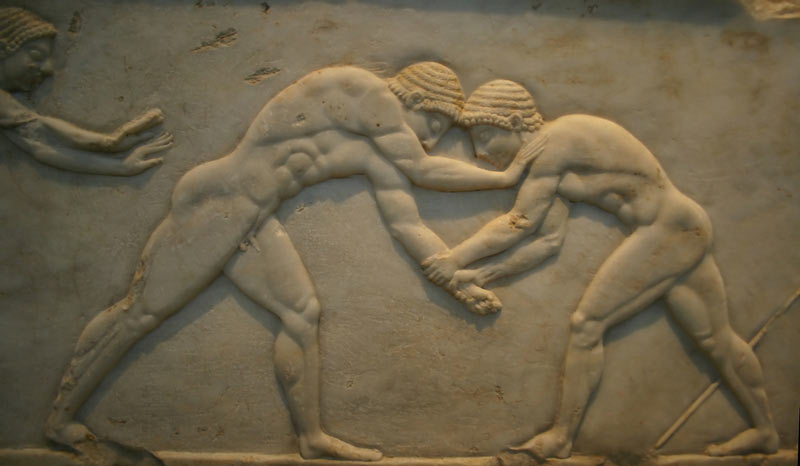

There were no pins in this Greek style of wrestling, and the goal of the wrestlers was to throw the other to the ground three times. A wide array of holds and throws were used, a few of which look a bit like a body slam.

The contract includes a clause that Demetrius is still to be paid if the judges realize the match is fixed and refuse to reward Nicantinous the win. If "the crown is reserved as sacred, (we) are not to institute proceedings against him about these things," the contract reads. It also says that if Demetrius reneges on the deal, and wins the match anyway, then "you are of necessity to pay as penalty to my [same] son on account of wrongdoing three talents of silver of old coinage without any delay or inventive argument."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The translator of the text, Dominic Rathbone, a professor at King's College London, noted that 3,800 drachma was a relatively small amount of money — about enough to buy a donkey, according to another papyrus. Moreover, the large sum Demetrius would forfeit if he were to back out of the deal suggests his trainers would have been paid additional money Rathbone said.

The match fixing took place at an event honoring Antinous, the deceased male lover of the Emperor Hadrian (reign A.D. 117-138). After Antinous drowned in the Nile River nearby, the town of Antinopolis was founded in his honor, and he became a god, and statues of him were found throughout the Roman Empire. [Photos: The Secret Passageways of Hadrian's Villa]

The games had been going on for more than a century by the time this contract was created, and brought benefits for the people of Antinopolis. For instance, "You get the visitors; you get the crowd; you get the trade; you get the prestige," Rathbone told Live Science.

The contract was found at Oxyrhynchus, in Egypt, more than a century ago by an expedition led by archaeologists Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt. It was translated for the first time by Rathbone and published in the most recent volume of The Oxyrhynchus Papyri, an ongoing series that publishes papyri from this site. The transcription of the text was done by John Rea, a now-retired lecturer at the University of Oxford and Rathbone did the translation.

The Egypt Exploration Society owns more than 500,000 papyrus fragments from this site, and they are now kept at the Sackler Library at Oxford.

Why offer a bribe?

In the modern world, scandals involving bribes to athletes, or athletic officials, often revolve around gambling or attempts to reward a medal to athletes from a particular country.

The winners of ancient games would sometimes be paid sizable amounts of money, or receive lifetime pensions from their hometown, Rathbone said. However, he noted, there was no prize at all for coming in second.

"In ancient competitions, coming first is the one and only thing — no silver, no bronze," Rathbone said. Additionally, the cost of training athletes was considerable. Athletes from wealthy families could pay their own way, but athletes from less-well-off backgrounds could find themselves in debt to their trainers.

"The trainer is going to pay for your food, your accommodations and so on for your training, so you end up in debt to him," Rathbone said.

In this winner-takes-all situation, both sides may have decided to curb their risks by making a deal to fix the match, Rathbone said.

"If you were confident you would win, normally you would go for it," he said. "If you're not sure you would win, maybe you're cutting your risk by saying, 'At least I get the bribe,'" Rathbone said.

Why write up a contract?

But researchers still wonder, why did the guarantors for the athletes create a written contract recording the agreement? "That's the really bizarre thing; isn't it?" Rathbone said, noting that if either side reneged on the deal, it would be hard to take the matter to court.

He has also noted oddities in the way the contract was drawn up. "It doesn't look as though they've actually gone as far as getting a scribe with legal knowledge to do this for them, which makes you wonder if it's a bit of an empty thing," Rathbone said. "It's not really likely that either side is going to [seek recourse] if the other defaults."

Although this is the only known contract recording a bribe between ancient athletes, there are references in ancient sources indicating that bribery in athletic competitions was not unusual. By the time of the Roman Empire, bribery in athletic competitions was getting more prevalent as the events became more lucrative, Rathbone said.

"There are sources [indicating] that things had got a bit worse in the Roman Empire when there were more games and when there were more financial rewards, particularly these municipal pensions," Rathbone said. These pensions consisted of payments that an athlete's hometown awarded to winners and could continue for the rest of their life.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.