Searching High and Low for Dark Matter (Q+A)

Bruce Lieberman is a freelance science writer based in San Diego, Calif. He frequently writes about astrophysics for The Kavli Foundation and has also written for Air & Space Magazine, Sky & Telescope, Scientific American and other media outlets. He contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights

In late February, on behalf of The Kavli Foundation, I attended an annual conference of dark matter hunters — men and women on a common quest to identify the unknown stuff that makes up more than a quarter of the universe.

At Dark Matter 2014, held at UCLA, more than 160 physicists from around the world discussed their latest findings and technologies, and they shared their hopes and frustrations in solving one of cosmology's biggest mysteries. So where does the hunt stand?

As part of a series of discussions about the universe conducted by The Kavli Foundation, I had the opportunity to speak with three leading physicists at the conference about its biggest highlights and prospects for future progress.

Joining the conversation were Blas Cabrera, professor of physics at Stanford University, Member of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC) at Stanford, and spokesperson for the SuperCDMS dark matter experiment; Dan Hooper, scientist in the Theoretical Astrophysics Group at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, associate professor in the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Chicago, and senior member of the Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics (KICP) at Uchicago; and Tim Tait, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California, Irvine, and Member of the university's Theoretical Particle Physics Group.

The following is an edited transcript of the discussion.

THE KAVLI FOUNDATION: Almost everyone at the conference seems to think we're finally on the path toward figuring out what dark matter is. After 80 years of being in the "dark," what are we hearing at this meeting to explain the optimism?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

BLAS CABRERA: This conference has highlighted the progression of larger and larger experiments with remarkable advances in sensitivity. What we're looking for is evidence of a dark matter particle, and the leading idea for what it might be is something called a weakly interacting massive particle, or WIMP. We believe the WIMP interacts with ordinary matter only very rarely, but we have hints from a few experiments that might be evidence for WIMPs.

Separately at this conference, we heard about improved calibrations of last fall's results from LUX, the Large Underground Xenon detector that now leads the world in sensitivity for WIMPs above the mass of six protons — a proton being the nucleus of a single hydrogen atom. Under a standard interpretation of the data, the LUX team has ruled out a range of low-end masses for the dark matter particle, another major advance because it does not see potential detections reported by other experiments and further narrows the possibilities for how massive the WIMP might be.

Finally, Dan [Hooper] also gave a remarkable presentation here about another effort: to indirectly detect dark matter by studying radiation coming from the center of the Milky Way galaxy. He reported the possibility of a strong dark matter signal, and I would say that was also one of the highlights of the conference because it provides us with some of the strongest evidence so far of a dark matter detection in space. Dan can explain.

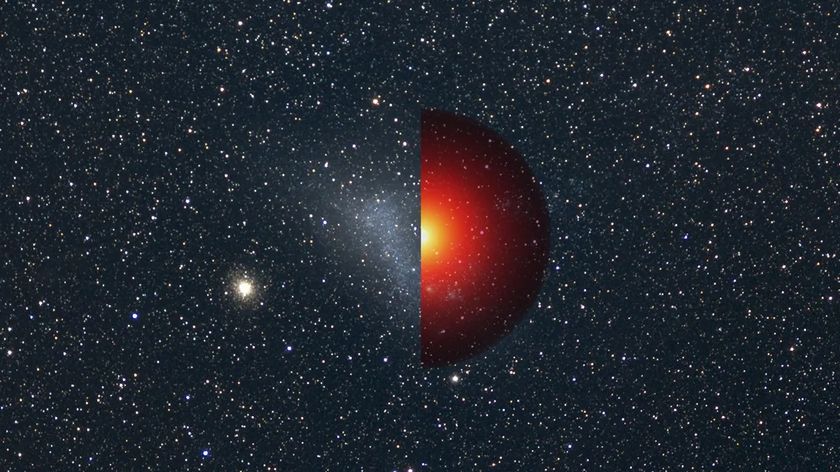

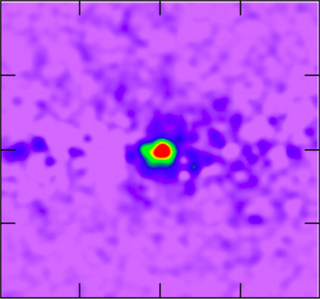

DAN HOOPER: Four and a half years ago, I wrote my first paper on searching for evidence of dark matter at the center of the Milky Way galaxy. And now we think we have the most compelling results to date. What we're looking at is actually gamma rays — the most energetic form of light — radiating from the center of the galaxy. I think that this is very likely a signal of annihilating dark matter particles. As Blas explained, we believe dark matter is made of particles, and these particles, by themselves, are expected to be stable — meaning that they don't readily decay into other particles or forms of radiation. But at the dense core of the Milky Way galaxy , we think they collide and annihilate one another, in the process releasing huge amounts of energy in the form of gamma rays.

TIM TAIT: We expect that the density of dark matter particles, and therefore the intensity of the gamma-ray radiation released when they collide, should both fall as you move away from the galactic center. So, you sort of know what the profile of the signal should be, moving from the center of the galaxy outward.

TKF: So Dan, in this case the gamma rays that we observe radiating from the center of the Milky Way match our predictions for the mass of dark matter particles?

HOOPER: That's right. We predicted what the energy

level of the gamma rays should be, based on established theories for how massive the WIMP should be, and what we've seen matches the simplest theoretical model for the WIMP. Our paper is based on more data, and we found more sophisticated ways of analyzing that data. We threw every test we could think of at it. We found that not only is the signal there and very statistically significant, its characteristics really look like what we would expect dark matter to produce — in the way that the gamma-ray radiation maps on the sky, in its general brightness, and in other features.

TKF: Tell me a bit more about this prediction.

HOOPER: We think that all the particles that make up dark matter were all produced in the Big Bang nearly 14 billion years ago, and eventually as the universe cooled a small fraction survived to make up the dark matter we have today. The amount that has survived depends on how much the dark matter particles have interacted with one other over cosmic time. The more they collided and became annihilated, the less dark matter survives today. So, I can basically calculate the rate at which dark matter particles have collided over cosmic history — based on how much dark matter we estimate exists in the universe today. And once I have the rate of dark matter annihilation today, I can estimate how bright the gamma-ray signal from the galactic center should be — if it's made of WIMPS of a certain mass. And lo and behold, the observed gamma-ray signal is as bright as we predict it should be.

TKF: What else caught everyone's attention at the conference?

TAIT: A really striking result was from Super Cryogenic Dark Matter Search, or SuperCDMS, the direct detection experiment that Blas works on. They didn't find any evidence for dark matter, and that contradicts several other direct detection experiments that have claimed a detection in the same mass range.

CABRERA: What we're looking for is an exceedingly rare collision between an incoming WIMP and the nucleus of a single atom in our detector, which in SuperCDMS is made from germanium crystal. The collision causes the nucleus of a germanium atom to recoil, and that recoil generates a small amount of energy that we can measure.

Direct detection experiments are situated underground to minimize background noise from a variety of known sources of radiation, from space and on Earth. The new detectors that we built in SuperCDMS have allowed us to reject the dominant background noise that in the past clouded our ability to detect a dark matter signal. This noise was from electrons hitting the surface of the germanium crystal in the detector. The new design allows us to clearly identify and throw out these surface events.

So, rather than saying, "Okay, maybe this background could be partly a signal," we can say with confidence now, "There is no background" and you have a very clean result. What this means is we have much more confidence in our data if we do make a potential detection. And if we don't, we're more confident that we're coming up empty. Eliminating background noise vastly reduces uncertainties in our analysis — whether we find something or not.

TKF: What caught everyone's attention on the theoretical side?

CABRERA: What struck me at this meeting is that nuclear physicists have recently written papers describing a generalized framework for all possible interactions between a dark matter particle and the nucleus of a single atom of the material that researchers use in their detectors; in the case of SuperCDMS, as I've explained, it's germanium and silicon crystals. These nuclear physicists have pointed out that roughly half of all possible interactions are not even being considered now. We are trying to digest what that means, but it suggests there are many more possibilities and a lot we still don't know.

TKF: Tim, with accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider in Europe, researchers are looking for evidence of supersymmetry, which could reveal the nature of dark matter. Tell me about this idea. Also, was anything new discussed at the meeting?

TIM TAIT: Supersymmetry proposes there are mirror particles that shadow all the known fundamental particles, and in this shadow world may lurk the dark matter particle. So, by smashing together protons in the LHC, we've tried to reveal these theoretical supersymmetric particles. So far, though, the LHC hasn't found any evidence for supersymmetry. It may be that our vision of supersymmetry isn't the only vision for physics beyond the Standard Model. Or maybe our vision for supersymmetry isn't a complete one.

TKF: The LHC is going to collide protons at much higher energy levels next year, so could that reveal something we just can't see right now?

TAIT: We hope so. We have very good reason to think that the lightest of the mirror particles in this shadow family is probably stable, so higher energy collisions could very well reveal them. If dark matter was formed early in the universe as a supersymmetric particle and it's still around — which we think it is — it could show up in the next round of LHC experiments.

TKF: When you think about the different approaches to identifying dark matter, has anything discussed at this meeting convinced you that one of them will be first?

TAIT: When you look at all the different ways of looking for dark matter, what you find is that they all have incredible strengths and they all have blind spots. And so you can't really say one is doing better than the other. You can say, though, they are answering different questions and doing very important things. Because even if you end up discovering dark matter in one place — let's say in the direct detection search — the fact that you do not see it at the LHC, for example, is already telling you something amazing about the theory. A negative result is actually just as important as a positive result.

HOOPER: The same goes with the direct detection experiments. I'm remarkably surprised that they haven't seen anything. We have this idea of where these supersymmetric particles and WIMP particles should show up in these experiments — at the LHC and in direct detection experiments — and yet lo and behold we got there and they are not there. But that doesn't mean they're not right around the corner, or maybe several corners away.

CABRERA: Given the remarkable progress over the past few years with many direct detection experiments, we would not have been surprised to have something rear its head that looks like a true WIMP.

HOOPER: Similarly, I think if you had done a survey of particle physicists five years ago, I don't think many of them would have said that in 2014 we've only discovered the Higgs — the fundamental particle that imparts mass to fundamental particles — and not anything else.

CABRERA: Now that the Higgs has been pretty convincingly seen, the next big questions for the accelerator community are: "What is dark matter? What is it telling us that we do not see dark matter at the LHC? What does that leave open?" These questions are being asked broadly, which wasn't the case in past years.

TKF: Was finding the Higgs, in a sense, an easier quest than identifying dark matter?

HOOPER: We knew what the Higgs should look like, and we knew what we would have to do to observe it. Although we didn't know exactly how heavy it would be.

CABRERA: We knew it had to be there.

HOOPER: If it weren't there it would have been weird. Now, with dark matter, there are hundreds and hundreds of different WIMP candidates that people have written down, and they all behave differently. So the Higgs is a singular idea, more or less, while the WIMP is a whole class of ideas.

TKF: What would a confirmed detection of dark matter really mean for what we know about the universe? And where would we go from there?

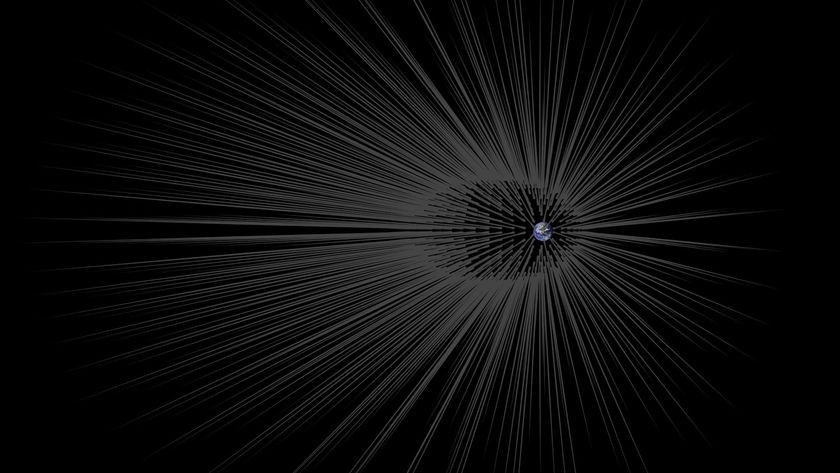

CABRERA: A discovery of dark matter with direct detection experiments would not be the end of the journey, but rather the beginning of a very exciting set of follow-up experiments. We would want to determine the mass and other properties of the particle with more precision, and we'd also want to better understand how dark matter is distributed in and around our galaxy. Follow-up experiments with detectors would use different materials, and we'd also try to map which direction the WIMPs are coming from through our detectors, which would help us better understand the nature of dark matter that surrounds the Earth.

Overall, a discovery would be huge for astrophysics and cosmology, and for elementary particle physics. For astrophysics we would have identified the dominant form of matter in the universe that seeded structure and led to galaxies, solar systems and planets, and ultimately to our Earth with intelligent life. On the particle physics side, this new particle would require physics beyond the Standard Model such as supersymmetry, and would allow us to probe this new sector with particle accelerators like the LHC.

TAIT: I think there's a lot of different ways you could look at it. From a particle physicist's point of view, we would now have a new particle that we'd have to put into our fundamental table of particles. We know that we see lots of structure in this table, but we don't really understand where the structure comes from.

From a practical point of view, and this is very speculative, dark matter is a frozen form of energy, right? Its mass is energy, and it's all around us. Personally, if I understood how dark matter interacts with ordinary matter, I would try to figure out how to build a reactor. And I'm sure that such a thing is not at all practical today, but someday we might be able to do it. Right now, dark matter just goes right through us, and we don't know how to stop it and communicate with it.

HOOPER: That was awesome, Tim. You blow my mind. I'm picturing a 25th century culture in which we harness dark matter to make an entirely new form of energy.

TAIT: By the way, Dan, I'm toying with the idea of writing a paper so we should keep talking.

HOOPER: I would love to hear more about it. That sounds great. So, to kind of echo some of what Tim said, the dark matter particle, once we identify it, has to fit into a bigger theory that connects it to the Standard Model. We don't really have any idea what that might look like. We have a lot of guesses, but we really don't know so there's a lot of work to do. Maybe this will help us build a grand unified theory — a single mathematical explanation for the universe — and help us, for example, understand things like gravity, which frankly we don't understand at all in a particle physics context. Maybe it will just open our eyes to entirely new possibilities that we just never considered until now. The history of science is full of discoveries opening up whole new avenues for exploration that were not foreseen. And I have every reason to think that that's not unlikely in this case.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.