'Gospel of Jesus's Wife': Doubts Raised About Ancient Text

The authenticity of the "Gospel of Jesus's Wife" has been debated since the papyrus was revealed in 2012. Now, new information uncovered by Live Science raises doubts about the origins of the scrap of papyrus.

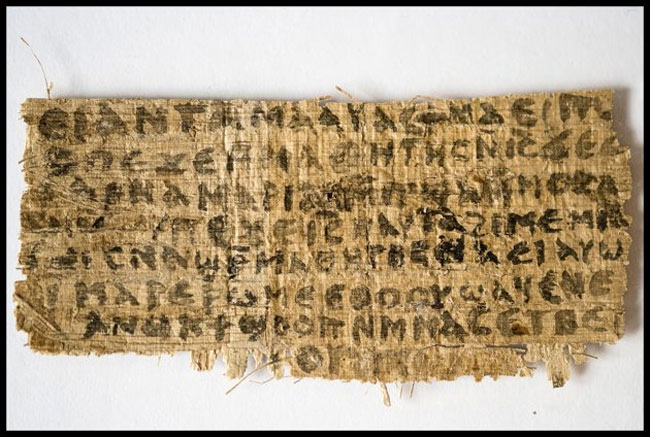

The gospel, written in the ancient Egyptian language Coptic, has made headlines ever since Harvard University professor Karen King announced its discovery. The business-card-size fragment contains the translated line "Jesus said to them, 'My wife …'" and also refers to a "Mary," possibly Mary Magdalene. If authentic, the papyrus suggests that some people believed in ancient times that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married.

At the time of the discovery, King tentatively dated the papyrus to the fourth century A.D., saying it may be a copy of a gospel written in the second century in Greek. [Read Translation of Papyrus]

Recently, several scientific tests published in the journal Harvard Theological Review have suggested the papyrus is authentic, but a number of scholars, including Brown University professor Leo Depuydt, dispute the papyrus's authenticity.

The document's current owner has insisted on remaining anonymous, and King has not disclosed the person's identity. However, in a recent Harvard Theological Review article, King published a contract provided by the current anonymous owner that King said indicates it was purchased, along with five other Coptic papyrus fragments, from a man named Hans-Ulrich Laukamp in November 1999 and that Laukamp had obtained it in 1963 from Potsdam in then-East Germany.

Provenance of a papyrus

In an effort to confirm the origins of the papyrus and discover its history, Live Science went searching for more information about Laukamp and his descendents, business partners or friends.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Our findings indicate that Laukamp was a co-owner of the now-defunct ACMB-American Corporation for Milling and Boreworks in Venice, Fla. Documents filed in Sarasota County, Fla., show that Laukamp was based in Germany at the time of his death in 2002 and that a man named René Ernest was named as the representative of his estate in Sarasota County. [Proof of Jesus Christ? 7 Pieces of Evidence Debated]

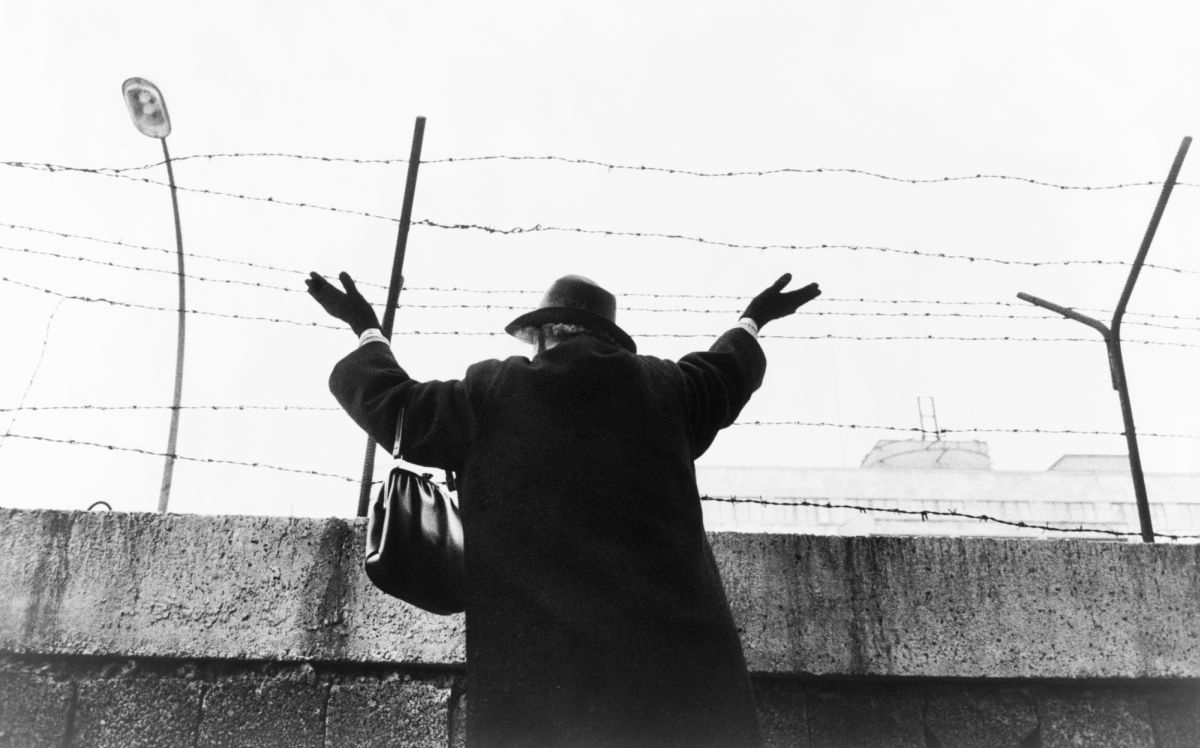

In an exchange of emails in German, Ernest said that Laukamp did not collect antiquities, did not own this papyrus and, in fact, was living in West Berlin in 1963, so he couldn't have crossed the Berlin Wall into Potsdam. Laukamp, he said, was a toolmaker and had no interest in old things. In fact, Ernest was astonished to hear that Laukamp's name had been linked to this papyrus.

While the documents name him as the representative of Laukamp's estate in Sarasota County, the two men are not related, and Ernest did not receive an inheritance, Ernest said, adding that, as far as he knows, Laukamp had no children and has no living relatives.

Ernest did not respond to specific questions about how he and Laukamp came to know each other, but it is clear from documents naming Ernest as estate representative that Laukamp placed a great deal of trust in him; one dealing with Ernest and the estate dates to when Laukamp was still alive and has his signature.

Another acquaintance of Laukamp — Axel Herzsprung, who was also a co-owner of ACMB-American Corporation for Milling and Boreworks — told Live Science (in German in an email) that while Laukamp collected souvenirs on trips, he never heard of him having a papyrus. To his knowledge, Laukamp did not collect antiquities, Herzsprung said.

Live Science searched for other living relatives, checking for records in Sarasota County, and contacted a Laukamp family living in Florida, but they are unrelated. As far as we could tell, Ernest is correct, and Laukamp has no living relatives.

More questions

In the Harvard Theological Review article, King noted that she also received, from the current anonymous owner, a copy of a "typed and signed letter addressed to H. U. Laukamp" that dates to July 15, 1982, from Peter Munro, a now-deceased professor at the Freie University Berlin.

King wrote that the letter said that "a colleague, Professor Fecht, has identified one of Mr. Laukamp's papyri as having nine lines of writing, measuring approximately 110 by 80 mm, and containing text from the Gospel of John ..."

King noted that this document doesn't mention the Gospel of Jesus's wife explicitly. However, if Ernest and Herzsprung are correct, and Laukamp never collected antiquities, the question becomes: Why and how does this document exist? Munro died in 2009, and the "Professor Fecht" may be Gerhard Fecht, an Egyptology professor at the Freie University Berlin who passed away in 2006, King wrote in her article.

The arguments against the papyrus's authenticity byDepuydtand others are complex, but a key problem they cite is that the Coptic text is full of errors, to the extent that it is hard to believe that an ancient Coptic writer could have composed it.

It's not known whether scholars will ever be certain that the text is authentic. More information on its provenance may be found in the future.

Live Science contacted King several times by phone and email beginning Wednesday, April 16, and received no response. A Harvard University representative has confirmed that King received our requests for comment.

Jonathan Beasley, the assistant director of communications at Harvard Divinity School, told Live Science that King is not available for an interview. However, Live Science did send her detailed information on our search into Laukamp's background.

Owen Jarus is continuing to look into the history of the papyrus. If you have any tips, please email him atowenjarus@gmail.com.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.