Virginia Volcanoes Linked to East Atlantic Islands

The youngest volcanoes on the East Coast share an unusual geological link with islands on the opposite side of the Atlantic Ocean, a new study reports.

The new findings could explain the enigmatic origin of the 48-million-year-old volcanoes, which punched through Virginia's fractured crust long after other fiery eruptions ceased along the East Coast. The surprisingly young volcanoes also offer clues into the tectonic forces molding eastern North America's mountains and hidden underbelly. The results appeared online April 10 in the journal Geology.

"These young volcanoes are in an area where no one would expect to see volcanic activity," said lead study author Sarah Mazza, a geologist at Virginia Tech. "These rocks are our only physical window into processes that helped shape Virginia and even the whole southeastern Appalachia as well."

The time span between when the Virginia volcanoes and the last known volcanic activity on the East Coast is about 150 million years. The older eruptions were triggered by the breakup of Pangaea, the supercontinent that included North America, Africa and South America. The stretching of Earth's crust as the supercontinent split allowed huge volumes of magma to escape from the mantle. Now, however, the East Coast is a passive margin, meaning there are no rifting or colliding tectonic plates to birth volcanoes or big earthquakes, as occurs along the West Coast. [In Images: How North America Grew as a Continent]

This long break between tectonic activity and the emergence of Virginia volcanoes has baffled researchers. So instead, many geologists said a hotspot could explain the origin of the volcanoes. Hotspots are plumes of magma that rise upward from the mantle. These long-lived mantle plumes are thought to fuel the volcanic chains in Hawaii and Yellowstone National Park. A proposed hotspot trail runs from Missouri to Maine and could have cooked Virginia about 60 million years ago.

But the results of the new study tell a more complex story — one that doesn't match with a hotspot origin, Mazza said.

Distant relatives

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

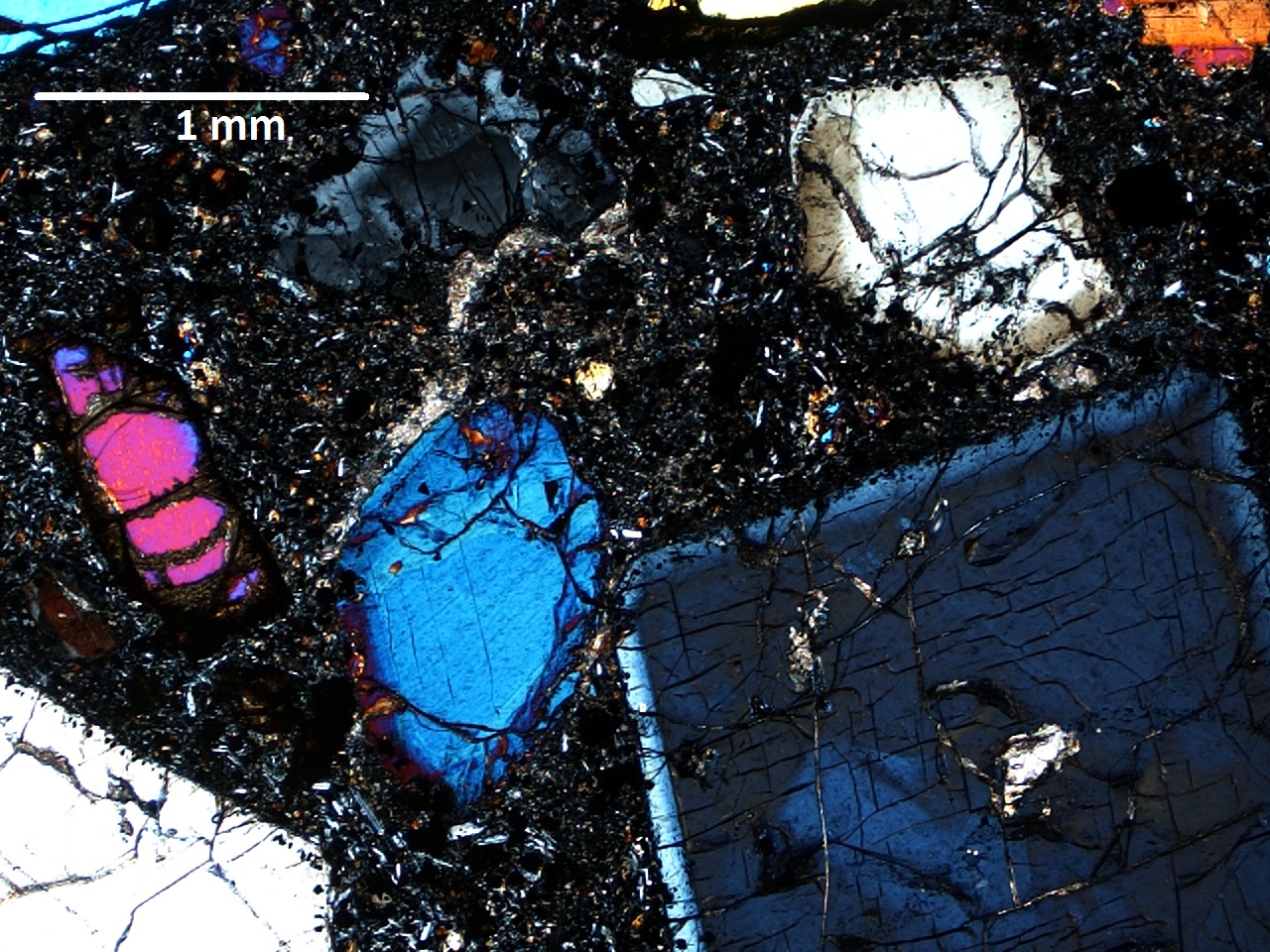

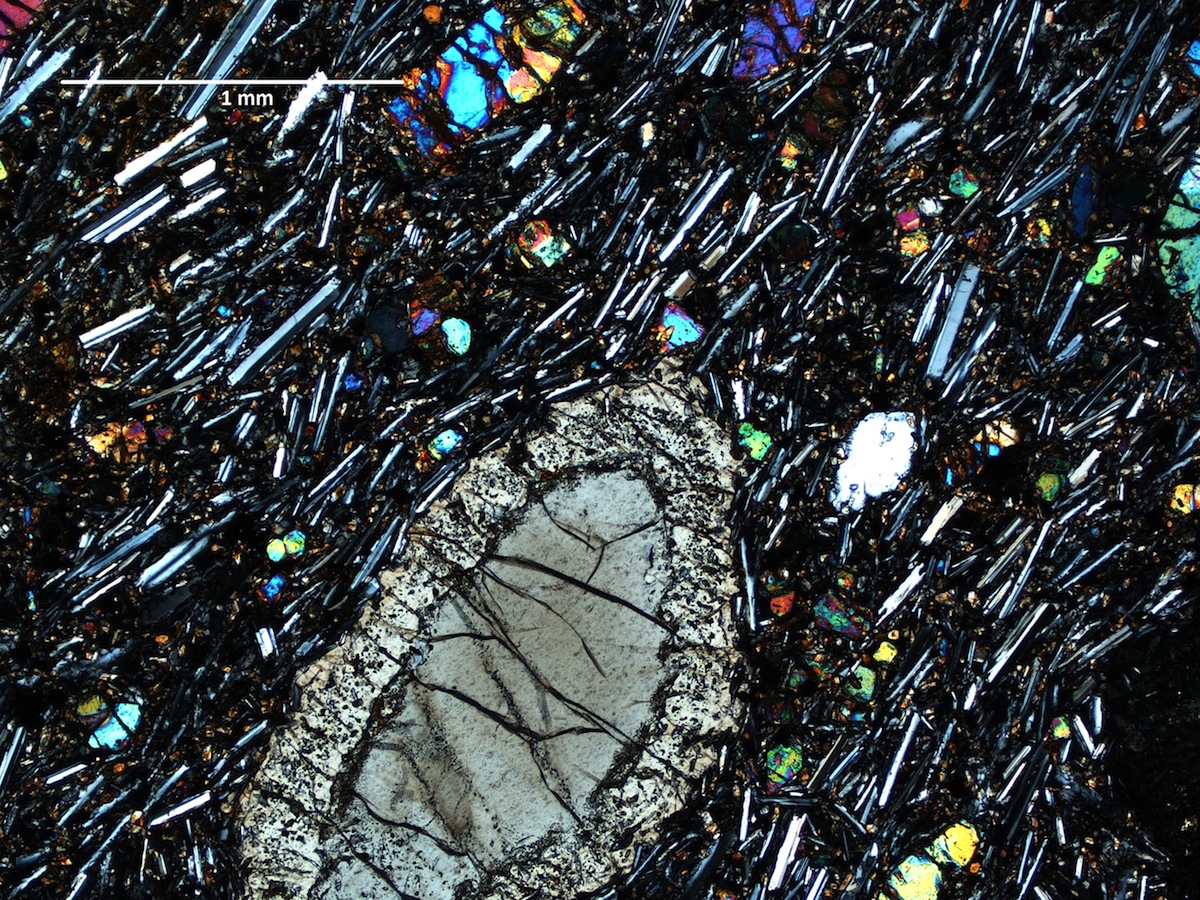

Mazza and her co-authors analyzed rocks from the volcanic swarm dotting Virginia and West Virginia. Two prominent examples include Mole Hill, west of Harrisonburg, Va., and Trimble Knob, in Highland County, Va. The gentle hills and knobs are long extinct. "You probably wouldn't know they were there unless you talked to a local," Mazza said.

Even though the lava chemistry is similar to hotspot volcanoes such as the Azores and Cape Verde Islands, the researchers concluded that a hotspot did not spark the Virginia volcanoes.

Here's why: First, the magma temperature is too low — roughly 2,570 degrees Fahrenheit (1,410 degrees Celsius), rather than the 2,732 F (1,500 C) measured at hotspot volcanoes, Mazza said. Second, the magma source is too shallow, she added. Third, the researchers precisely dated the eruptions to between 47 million and 48 million years ago, at least 10 million years after the hotspot passed through. "That difference is significant enough for us to think this hotspot probably wasn't the case," Mazza said.

Instead, the team proposes that magma reached the surface as pieces of the thick crust beneath Virginia peeled away like sloughing skin — a process called delamination. Afterward, magma seeped through the newly thinned crust, reaching the surface through pre-existing cracks in the overlying rock. In this model, the Virginia lava is the chemical cousin of eastern Atlantic volcanoes, because their sources are both deeply buried leftovers from the breakup of Pangaea, the supercontinent.

"The upwelling is allowing these [Virginia] volcanoes to sample a part of the mantle that is also seen over in the eastern part of the Atlantic," Mazza told Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

The shedding crust under Virginia could underlie topographic changes in the Appalachians, such as their recent face-lift. The mountains are more rugged than they should be, given their age and the tectonic quiescence of the East Coast.

"I hope this project is a good stepping stone for interpreting what is going on in the crust and the mantle," Mazza said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.