Powdered Alcohol, Seriously? A Health Risk We Don't Need (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Opening a bottle and pouring liquid into a glass isn’t exactly an arduous task but a US company hopes to release a powdered variety to make consuming alcohol that little bit easier – and more portable.

Earlier this month, the company Palcohol gained regulatory approval to market powdered alcohol in the United States. The approval was subsequently rescinded because of a labelling discrepancy, but Palcohol has corrected the labels and reapplied, hoping the product will be on the market by September.

With flavours such as cosmopolitan and lemon drop, the product is clearly targeted towards the alcopops market. But there are a number of obvious and hidden dangers that need to be considered before a product such as this should be made available in Australia.

What is powdered alcohol?

Drinking alcohol, or ethanol, is a highly volatile compound that boils under normal conditions at around 78 degrees Celsius; a lower temperature than water. As such, in its natural state, it’s impossible to produce in a powdered form. A solid form can be made only by freezing at minus 114 degrees but this turns back into a liquid as soon as you raise the temperature.

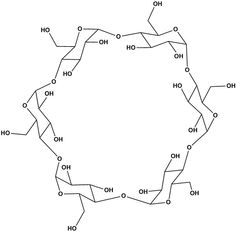

Instead, powdered alcohol is made using host-guest chemistry and a method for its production is described in several patents from the 1970s. It’s not clear what method Palcohol uses, but it’s likely to trap the alcohol inside of a circular molecule called a cyclodextrin.

Cyclodextrins have a shape similar to an ice cream cone where the bottom half has been bitten off. The cavity inside the cyclodextrin is perfect for storing small molecules.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cyclodextrins are used routinely in both medical products – such as the drug alprostadil, which is used to treat erectile dysfunction and ziprasidone, used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder – and in household items like the odour-reducing spray Febreeze. In the past, my research group has even examined cyclodextrins as potential delivery vehicles for anticancer drugs.

When the alcohol is trapped in the cyclodextrin, it doesn’t evaporate and together, they can be turned into a stable powder.

Misuse

The product could be used in a number of ways other than the intended just-add-water preparation, such as snorting the dry powder into the nose. Many compounds can be absorbed into the body from nasal tissue, such as antihistamine sprays to treat hay fever. Snorted alcohol has the potential to deliver alcohol to the brain without it having needing to go into systemic circulation in the blood stream.

We don’t know what the real risk of using alcohol in this way would be, as the research hasn’t been undertaken, but as a worse-case scenario the alcohol may significantly impair judgement and motor skills at levels far below those which normally give this effect.

In addition, snorting of any powders into the nasal cavity can cause severe irritation of the tissue leading to inflammation and bleeding.

One way for the company to address the misuse of their product in this way could be the inclusion of a bulking agent so that, gram per gram, each packet contains significantly less alcohol.

Overindulgence

The effects of alcohol and the damage it does to the body are well known, and the Australian government still advises that there is no amount of alcohol that is safe for everyone. The national guidelines, however, recommend women and men generally consume no more than two standard drinks per day to reduce their risk of alcohol-related disease, and no more than four drinks on a single occasion to minimise the risk of injury.

Despite years of advertising, education and the standard drinks guide, many adults are still unaware of how much alcohol is in different types of drinks like beer (3-10%), wine (8-15%) and spirits (15-40%) and therefore it can be easy for a person to drink more than they intended.

Given the ease with which powdered alcohol can be consumed compared with normal drinking volumes, consumers can very quickly ingest risky levels of alcohol. From the patents, the powdered alcohols contain anywhere between 30 to 60% ethanol. A 50 gram packet (half the size of a sherbert Wizz Fizz pack), could contain as much as 30 grams of ethanol; that’s almost twice the alcohol content in a stubby or can of beer.

Safety of ingredients

Cyclodextrins are approved for human use and are generally regarded as safe, although one size of the molecule, called beta-cyclodextrin, is known to cause kidney damage when it is injected into the blood stream.

More worrying is the possibility of powdered alcohol to be adulterated if bought over the internet. Such sellers may add prescription drugs – as was the case with this energy drink – or other unlisted ingredients to give their product an extra kick. These additives may pose serious dangers such as allergic reactions and overdoses.

Taking all of these potential dangers into consideration, the approval of any form of powdered alcohol in Australia needs to be considered very carefully before it is allowed for sale.

Further reading:

- Powdered alcohol will appeal to young drinkers, despite what the makers say

- Powdered alcohol and space diapers have something in common

Nial Wheate does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.