How I Found the Lost Desert Camp of Lawrence of Arabia (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

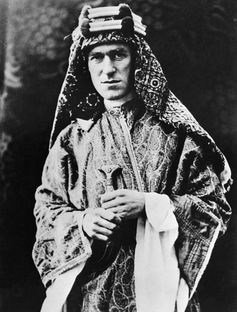

A fantastic coincidence, coupled with research, led to my discovery of a wartime camp in the Jordan desert that was occupied in 1918. This was a camp used by T E Lawrence, or “Lawrence of Arabia”, and British mobile units and was somewhat evocatively called “Tooth Hill”.

Earlier, these ancient landscapes of Edom had been thrust into modernity with the arrival of the Hejaz Railway, built by the Ottoman Turks in 1904. Ostensibly a holy railway built to transport pilgrims to the cities of Medina and Mecca, its capacity to transport troops re-militarised the landscape. This threatened British interests in Egypt and the Suez Canal, Britain’s main artery to India.

In July 1917 a young British officer called T E Lawrence captured the key town of Aqaba on the Red Sea, surprising both the British and Turkish high commands, who had considered it impossible. This enabled the Northern Arab Army of Emir Faisal to move northwards and the British to establish a beach-head and mount raids against the Turkish defences along the railway.

The British base expanded. By October, a small flight of aircraft was operating from a desert landing strip. Mobile British forces with Rolls Royce armoured cars and Talbot trucks carrying ten-pounder Indian mountain guns were able to operate in the hinterland.

In April 1918 these forces gathered overnight at the Tooth Hill camp to begin a series of raids on the fortifications at Tel Shahm, Wadi Rutm and Mudawwara. Today these are just north of Jordan’s border with Saudi Arabia.

It was while reading T E Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom that the possibility of finding this camp first occurred to me. The opening lines of chapter 105 read: “Our old camp behind the toothed hill facing Tell Shahm station.” This always caught my imagination. Where was this toothed hill and why did Lawrence make reference to it?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lawrence’s own elaboration provided the first clue:

It was a wonderful show, for the cars were parked geometrically here, and the armoured cars placed there…

Then other pieces of evidence began to surface. One was found in the war diary entries of X Flight RAF. It was a sketch map drawn after a reconnaissance flight made in early April 1918 in preparation for the raids on Tel Shahm. Flying without maps and with only a compass for navigation the pilots used familiar landmarks to guide them back to their airstrips. Without aerial cameras the pilots had to draw maps from memory. In this case, the pilot had noted the position of a significant landmark, and called it Tooth Hill.

The final clue, oddly, came in a coffee break at a conference. A Lawrence researcher I knew came across to me and asked: “I don’t suppose you know where this is, do you?” He showed me a photograph of several Rolls Royce armoured cars, parked in front of a distinctively shaped hill. My knowledge of the archives, Lawrence’s words and the landscape, combined with the photograph, lead to what can only be described as a eureka moment for me.

Six weeks later, walking across the desert to the site, we encountered broken glass, pot shards and spent cartridge cases lying around what appeared to be the site of a camp fire. The pottery looked like fragments of rum jars, a ubiquitous commodity in the British army on the Western Front, but not seen before in Jordan. Picking up the first piece of stoneware I turned it over and saw the initials SRD, the acronym for Service Ration Depot, a diagnostic inscription for these gallon jars.

Over the next two days a team of archaeologists, lead by my colleagues Nicholas J Saunders and Neil Faulkner, meticulously excavated the camp fire and recorded the many artefacts scattered around. Meanwhile metal detectors scanned the surrounding area and found shell cases and small items such as spark plugs that indicated vehicles had been maintained on this site.

Britain’s recent military deployments have seen its forces engaging insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan; fighting and defending fixed bases such as Camp Bastion against a highly mobile and fluid guerrilla force. But here in Jordan it was the British who were the insurgents in 1918.

Lawrence had given the concept of insurgency much thought. He realised that the small British contingent supporting regular and irregular Arab troops and armed Bedouin could defeat the Turks who outnumbered them significantly.

The forces camped at Tooth Hill with Lawrence were able to move freely. They could race across the desert on hit-and-run raids against the Turks, who were static, tied down to defending fixed locations along the railway. With mobile armour and field guns directed by aerial reconnaissance these raids were among the first combined actions seen in Arabia.

This site we discovered last year is significant because it is the only British campsite to be found in Jordan from the World War I era. Used for perhaps less than ten days its ephemerality and remoteness had concealed it for 94 years. It is fantastic to be able to connect such a place to Lawrence, and I like to think that here too, he was:

Happy with bully-beef and tea and biscuit, with English talk and laughter round the fire, golden with its shower of sparks from the fierce brushwood.

John B Winterburn does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article. He is the Landscape Archaeologist for The Great Arab Revolt Project.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.