In Photos: Leonardo Da Vinci's 'Mona Lisa'

The beginning of 3D artwork

Leonardo Da Vinci's Mona Lisa painting may be part of the oldest 3D artwork, say two visual scientists. (Shown here, a retouched picture of the Mona Lisa, digitally altered from its original version by modifying its colors.)

Mona Lisa

The famous Mona Lisa painting exhibited in the Louvre museum in Paris (right), and her sister painting the Museo del Prado in Madrid (left).

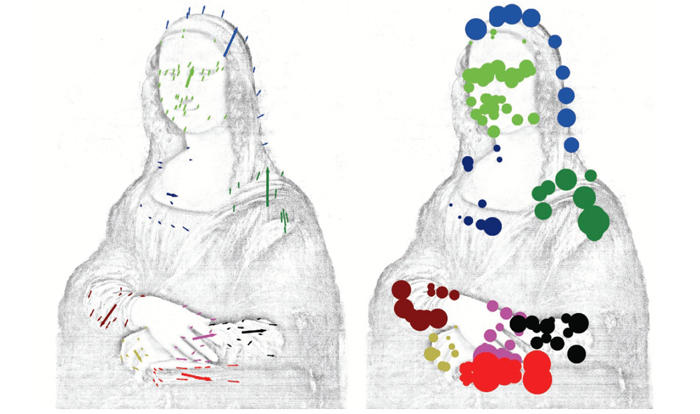

Perspective and perception

The perceptual change between the two paintings is visualized by linear trajectories between corresponding landmarks on the Louvre and Prado. The researchers grouped 124 trajectories into nine categories: face (neon green), hair (blue), upper-left body (dark green), body right (dark blue), left arm (black), right arm (brown), left hand (light green), right hand (pink), chair (red). The thick arrows indicate the average trajectories for each category. The changed perspective can most easily be observed in the picture elements showing Mona Lisa's hands and her head.

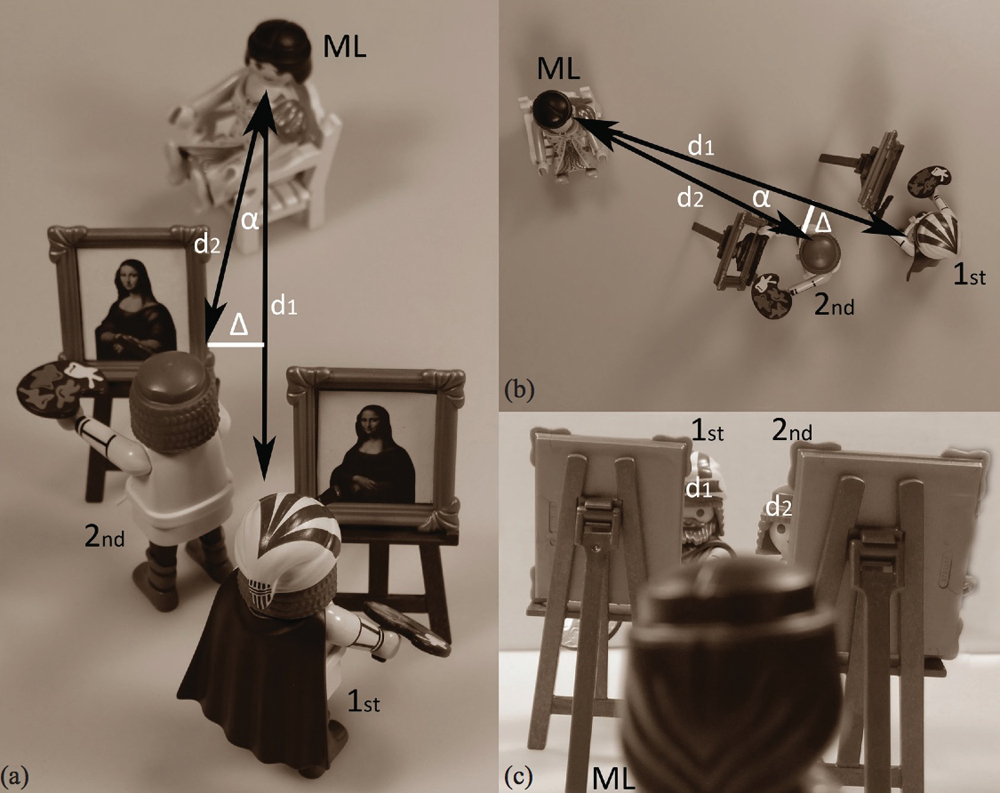

The studio set up

A schematized setting of da Vinci's studio when the pair of La Giocondas or Mona Lisas was painted. (Symbols: Mona Lisa (ML), painter of Louvre version (1st), painter of Prado version (2nd), and distances between ML and the first and second painters (d1 and d2, respectively), with the other two symbols representing the angle between the two perspectives and the disparity that would arise if both artists were at the same spatial distance (d2) from the model.

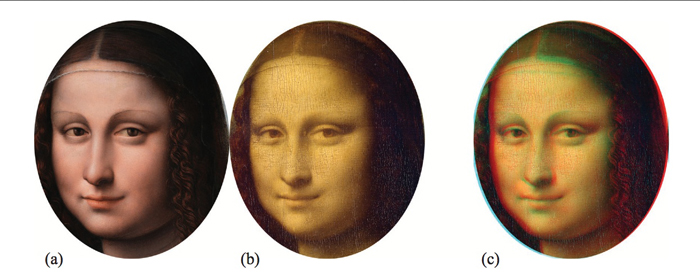

The face

Here, a detailed view of the face regions of the Prado version of the Mona Lisa (a) and the Louvre version (b), along with a red–cyan anaglyph combining both versions (c).

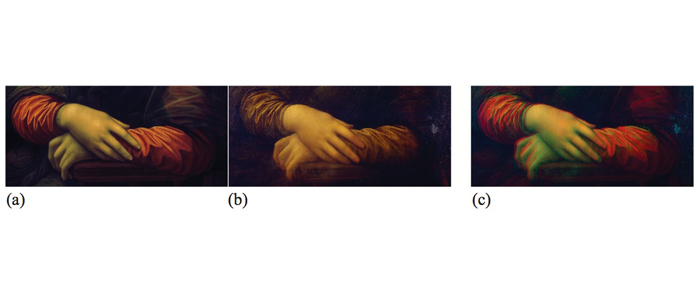

Versions compared

Here, a detailed view of the hand regions of the Prado version of the Mona Lisa (a) and the Louvre version (b), along with a red-cyan anaglyph combining both depictions. The colors of the Prado version have been adjusted to the Louvre version.

A 3D view

Mona Lisa's hand region shown here in a red-cyan anaglyph, or the 3D view.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

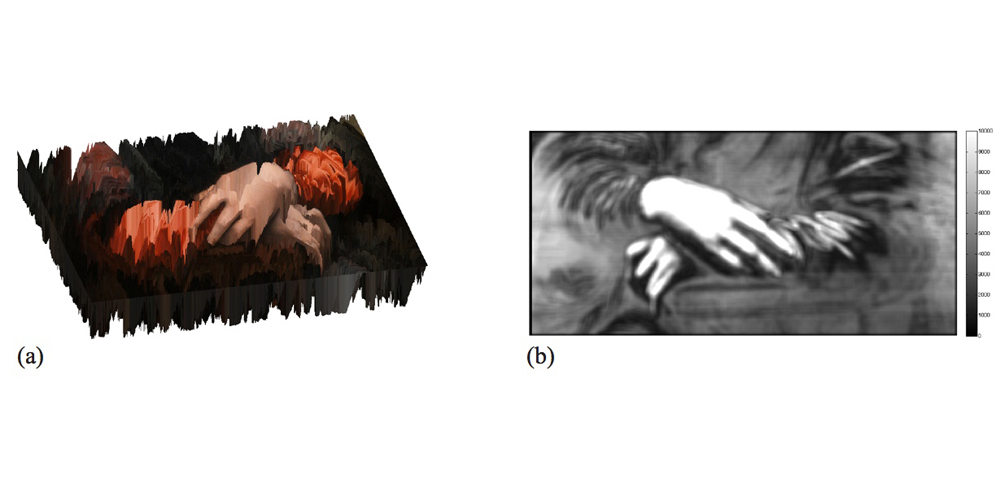

The hands

A 3D reconstruction (a) and matching costs of the hand regions using the Fast Matlab Stereo Matching Algorhithm by Wim Abbeloos.

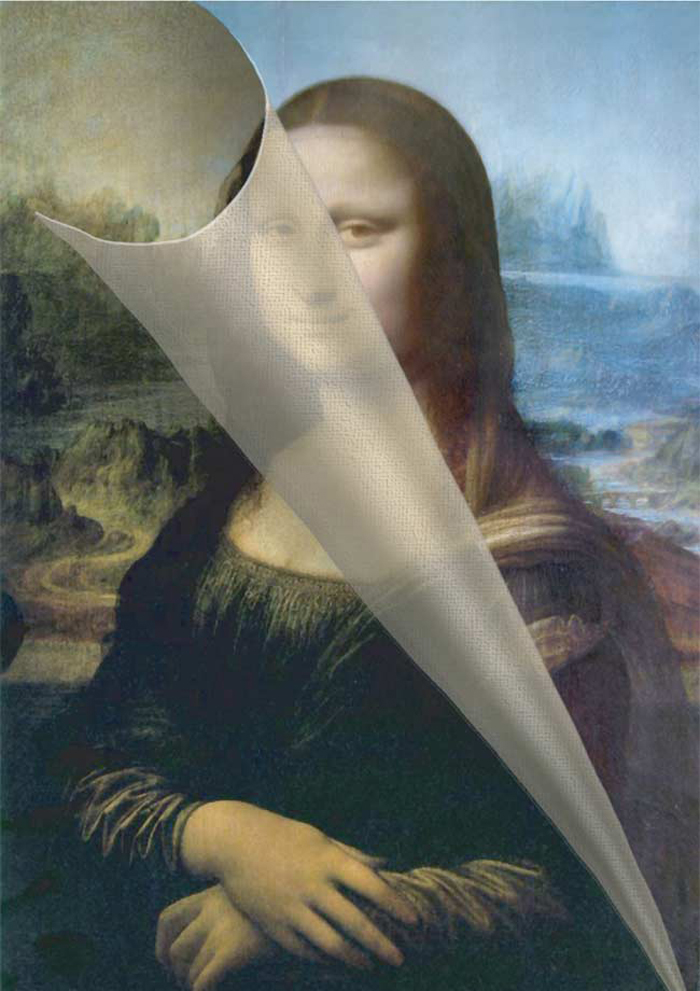

Secrets revealed

Plenty of secrets have been revealed about the Mona Lisa. For instance, in 2007, researchers reported they had scanned the painting with a 240-megapixel Multi-spectral Imaging Camera, which uses 13 wavelengths from ultraviolet light to infrared (shown here in infrared and visible light). The resulting images peel away centuries of varnish and other alterations, shedding light on how the artist brought the painted figure to life and how she appeared to da Vinci and his contemporaries.

A surprising discovery

In 2012, scientists discovered that beneath layers of black paint, a seemingly insignificant "knock-off" of the Mona Lisa in the Museo del Prado in Madrid was in actuality very close to the original hanging in the Louvre Museum in Paris, revealing the same subject with the same mountain landscape background. That painting may have been painted by Da Vinci or possibly one of his students.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.