Six Bizarre Feeding Tactics from the Depths of Our Oceans

Life in the deep

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Sea life can be fascinating and terrifying at the same time. Some creatures look beautiful on the outside but harbour darkness within. Some of the scariest tactics of the deep sea go on display when these creatures eat. Here are six of my favourite feeding strategies.

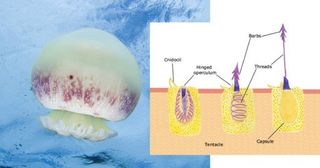

Jellyfish

Jellyfish, corals and anemones are all cnidarians that have stinging cells on their tentacles called nematocysts. Jellyfish slowly drift along in the currents, swimming gracefully by inflating and deflating their bells, and catching unsuspecting creatures that drift by in these stinging tentacles. Food is then transferred into the digestive tract by oral tentacles that ring the mouth.

Pink and yellow sea cucumber

Speaking of tentacles, another cool way to catch a meal can be seen in the pink and yellow sea cucumber and its relatives. This type of sea cucumber finds a good spot where water is flowing then holds its frilly tentacles out to capture food particles as they float by. It then gracefully plunges each tentacle individually into its mouth and pulls off all of the delicious edible bits. It’s like eating with a rotating collection of flexible forks.

Feather stars

Sea cucumber tentacles are akin to the mucus-coated tube feet used by their cousins, the feather stars. They hold their arms aloft, each tube foot stretched out and sticky, ready to catch some snacks. Passing plankton, bacteria and detritus gets trapped in the mucus and after a fair bit of arm waiving it’s time to gather the goods.

The tube foot furthest from the feather star’s mouth bends down to get closer to its neighbouring foot, which wraps itself around the first, sweeping it and bringing with it a sticky picnic. The foot below that does the same: wrapping itself around its neighbour and scraping the food off the end. It then delivers the meal to the feather star’s mouth.

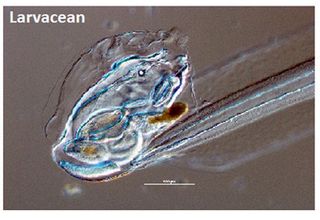

Larvaceans

There are more animals that make the most of mucus to catch a meal, such as larvaceans. They tend to be a few centimetres long and look a lot like a tadpole, with a round body at one end and a long tail at the other. On their own they are not the most inspiring of creatures, but the way they dine is definitely worth a mention.

Each larvacean builds it’s own mucus house that serves as a filter for the ocean’s fine foods. Their beating tail creates a current that keeps this sticky net open and brings in the grub. To deal with filters getting clogged, larvaceans simply throw out the old house and create a new one roughly every hour, ready to trap more tasty morsels.

The discarded house goes on to make a delicious meal for deep sea animals, rapidly falling to the deep ocean because all the trapped material makes it pretty heavy. Most material falls slowly to the deep – and it’s often eaten up on the way, but larvacean creations fall so fast that deep sea critters can enjoy a packed lunch of pretty fresh food.

Humpback whales

Humpback whales form groups and then carefully coordinate, blowing bubbles to corral schools of fish together into one spot. Once the schools are combined into one big ball of lunch, the whales swim upwards through the school of fish with their mouths open.

Sea star

Imagine a mussel feeling safe and secure in its shell. Suddenly, a purple sea star appears and starts prying open that shell, showing every intention of eating the tiny creature inside.

The good news is, mussel muscles are very strong so the sea star can only open the shell of its intended victim a tiny bit. The bad news is, sea stars have the ability to invert their stomachs. Even though it has only opened he mussel’s shell slightly, it can push its stomach out of its body through the tiny space, digesting it in its own home.

Jessica Carilli blogs at Saltwater Science (http://www.nature.com/scitable/blog/saltwater-science)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.