The Cartoon Thing: Why Are Female Scientists Missing? (Op-Ed)

Sai Pathmanathan is a science education consultant in the United Kingdom. She contributed this article, the second in a two-part series about growing up in a gender-defined science culture, to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

I have given many talks to schools in the UK and across the United States regarding neuroscience, science in the media, and careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) — and it never ceases to amaze me how many students inherently love science, even if they are not interested in a science career. It's true that some may not know what such a career involves, but I sometimes think that if a young person makes a conscious decision to not pursue such a career, it should be allowed. Trying to make someone choose STEM when they are not interested is not the way forward. Showing everyone what STEM subjects can help them with, is.

But what if they want to become a researcher, but don't think a STEM career is possible for them just because they are the wrong gender? And how would a child get such an idea?

In many primary schools, if the children don't know a scientist personally or a scientist has never visited the school before, their ideas about scientists tend to come from television. Those of us who have asked children to "draw a scientist" (e.g. see the (In)visible Witnesses research reports) see the vast majority represented as goggled, white-haired, old male scientists surrounded by explosive chemistry experiments and runaway lab animals.

Cartoons often depict scientists as evil baddies conducting dangerous or unethical experiments — but even if shown to be goodies, they will almost undoubtedly be male. However, those children who have a female resident scientist, such as at Lab_13 at Irchester Primary School, UK. (Lab_13 is a space run by young people for young people, dedicated to inquiry, investigation, innovation, creativity and the "what if…?" The children also make videos, for example: "Can TV shows help get girls in STEM?") The Lab_13 students draw more pictures of a friendly, female scientist when asked. And it wasn't just the girls who did so.

There are web pages and organizations that have compiled lists of fictional scientists and engineers, although it is often difficult to find the females, let alone animated ones. There are Pinterest boards of animated females in science, such as Susan and Mary Test, and those "intellectually curious" about science and mathematics or medicine, such as Doc McStuffins. And we could add Lisa Simpson and Sandy Cheeks. But surely there must be more?

I have wondered … did I see any growing up? One in particular springs to mind. Forgetting the 'evil scientist' Professor Nimnul in it, the cartoon Disney's Chip 'n' Dale Rescue Rangers also had a character named Gadget: a female mouse who invented machines and devices from household equipment. She was like an animated murine MacGyver. Watching her hold her own amongst the rest and being seen as the most intellectual in the group was pretty inspirational, even if she was a mouse. Is this why I became interested in STEM? Maybe. Perhaps popular culture could have a role to play in how people see science and whether children can imagine themselves as scientists. [Top 5 Myths About Girls, Math and Science ]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, the reality appears to be much more complex. Most STEM professionals can't pinpoint exactly what it was that turned them onto STEM . And neither can I. The ASPIRES study, which tracked the development of young people's science and career aspirations from age 10-14, mentions 'science capital' — i.e., a student is likely to want to go into a science career depending on his or her family's science-related qualifications, understanding and interest, and knowing someone in a science-related career.

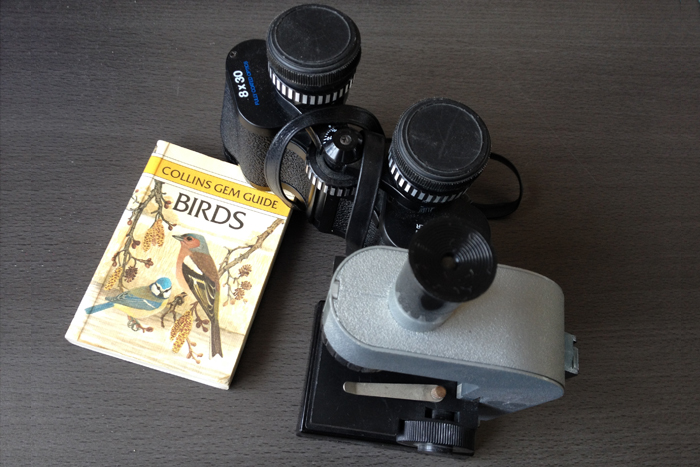

I have a family that promoted education and science. I grew up wanting to know more about wildlife, had my own set of binoculars for bird watching and a microscope set for looking at my dissected specimens (usually of the botanical kind). I fixed things, invented things, and made crystal radios and my own perfume. I had amazing science teachers and even did science experiments at primary school. I watched some science educational shows on television, enjoyed the science in cartoons, and may have come across a female scientist or two. Did any one of these contribute to my wanting to pursue a STEM career? I think so, and I rather hope it was a product of them all.

However not everyone is as lucky to have the same support as I had growing up. For those without access to such science capital, perhaps over a period of time, encountering a broader range of attainable role models — including a stronger representation of female scientists — could make a difference to future career aspirations. I personally feel a sense of responsibility to get out there and do my bit. And so do other colleagues. There may be a lot still to do…but we are making a difference.

Author's note: For more on this topic, listen to the Imagining Scientists audio feature and view their teaching resource.

Pathmanathan's last op-ed was "The Toy Thing: It Was Never About Pink or Blue." The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.