#Earthquake! Tweets Beat Official Quake Alerts

The fastest earthquake alerts come from social media networks, not the U.S Geological Survey's seismic underground sensors, ongoing research finds.

As soon as the Earth starts rumbling, Twitter users flood the network with pithy, publicly available tweets that the USGS uses to pinpoint an earthquake's source in less than a minute, according to findings presented May 2 at the Seismological Society of America's annual meeting in Anchorage, Alaska. Without Twitter, it takes the USGS anywhere from two to 20 minutes to precisely locate an earthquake and judge its size with seismometers, which are instruments that monitor ground motion.

Twitter has 255 million active users worldwide, and the USGS, using a software tool, tracks the word "earthquake" in languages ranging from Tagalog to Spanish. The Twitter conversation ranged from 600 tweets per minute following a magnitude-5.8 earthquake offshore of Java to 4,000 tweets per minute after the 2011 Virginia earthquake to more than 10,000 tweets per minute after the massive 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan.

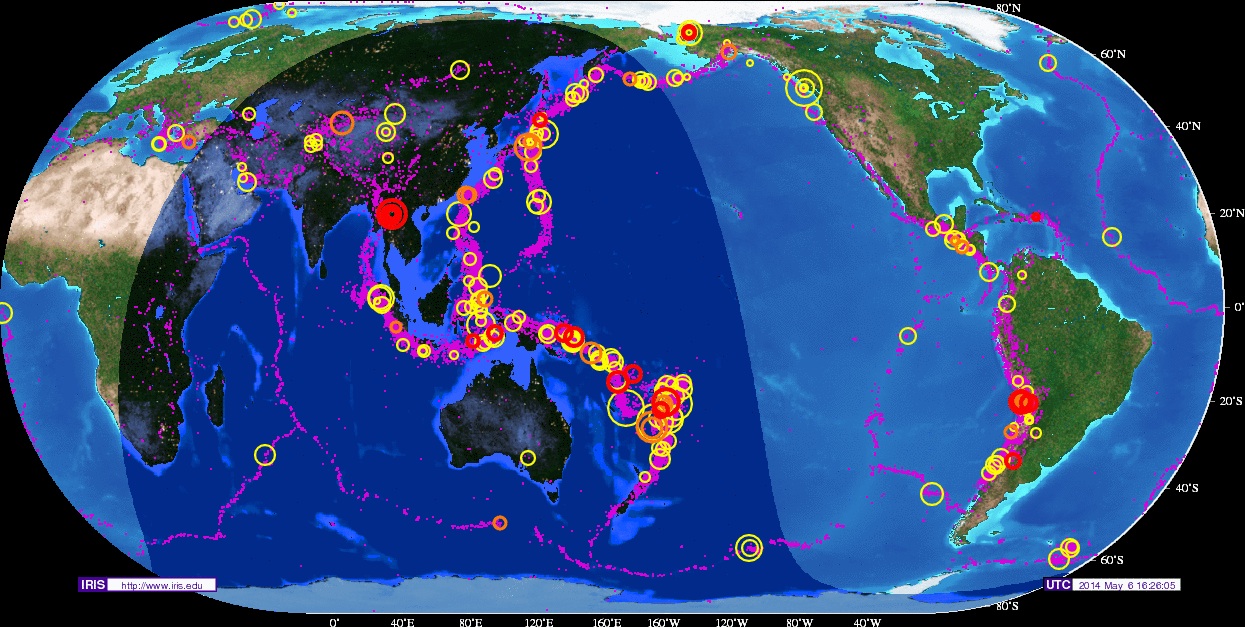

"Frequently, it's the first indication of a widely felt event," said Paul Earle, director of operations for the USGS National Earthquake Information Center, who presented the findings. "People like to talk about earthquakes." [Image Gallery: This Millennium's Destructive Earthquakes]

Holy $*#&, earthquake!

On average, in the past 10 months, the USGS software tool detected 19 earthquakes a week, or about two to three per day, Earle told Live Science. About half were detected in less than a minute, and 90 percent in less than 2 minutes, he said. The weakest was a magnitude-1.4 quake, and the strongest was a magnitude 8.2. Anyone can see the number of tweets per minute for a recent earthquake by following the USGS Twitter account @USGSted.

However, with a 10 percent error rate, a Twitter app won't replace official earthquake instruments anytime soon. Location accuracy is a major hurdle — just 1 to 2 percent of users tag their tweets with a GPS location, and only 30 to 40 percent add their hometown. And the global seismometer network detects thousands of quakes that would otherwise go unnoticed, such as those on the seafloor. So, what's the point of tracking these tweets?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With Twitter, Earle said, seismologists can guess the size and impact of an earthquake, sometimes even before seismic waves finish rolling through a populated region. Tweets help fill the data gap in regions with a sparse seismic network. The software tool also gives seismologists a head start in manually processing quakes that were widely felt, but might be slow to show up, or too small for the automated network to detect.

Here are some examples:

- When a magnitude-4 earthquake shook Maine in October 2012, Earle got the news through Twitter before some New England residents felt the shaking, he said.

- Earle said he knew that Chile had just been struck by a powerful earthquake last month because of tweets. Chileans — Twitter's most prolific earthquake tweeters — employ two different words for earthquake: temblor and terremoto. A temblor is an average earthquake, unlikely to cause major damage, whereas terremoto is reserved for really big quakes. And on April 2, when a magnitude-8.2 earthquake hit, the number of people tweeting "terremoto" instead of "temblor" spiked.

- Tweets from Japan immediately after the Tohoku earthquake spanned all of the island of Honshu and southern Hokkaido. The wide coverage prompted the USGS to bring in more staff to analyze the 2011 earthquake — expecting a large impact — because the quake was seismically detected with a location, but no size, after 3.8 minutes. [In Photos: Tohoku Japan Earthquake & Tsunami]

"Twitter provides earthquake detection from an independent source, which is important in a response situation, when you're trying to see if all the observations make sense," Earle said. "We generally get these detections before we have actual magnitudes, so it gives you an idea of what you're looking at."

Earthquake!

— Dave Snider (@DaveSnider) May 5, 2014

Expanding the network

The USGS is now exploring whether tweets can be used to estimate the intensity of shaking and the extent of earthquake damage, to help first responders. Separately, a team of Stanford University researchers will present a study exploring how analyzing tweets could improve the accuracy of real-time shaking maps at the annual meeting of the National Conference on Earthquake Engineering in July.

The USGS first started testing Twitter earthquake detection in 2008, after Twitter users beat traditional media outlets in reporting the Wenchuan earthquake in China. Researchers built the software with funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The tool plucks relevant tweets from the stream of chatter in a manner similar to how automated software picks earthquake waves from seismograms, the graphical output of a seismometer.

To limit false positives, the software discards tweets with links (which are likely to be from someone who wasn't there and is sharing a news story) and tweets longer than seven words. "In the initial stages, people are tweeting fast and not saying much," Earle said. And there's one tired gag involving simultaneous car alarms that apparently never gets old. "I've collected over 22 million tweets, and one thing I've learned is that people use the same joke about earthquakes over and over again," he said.

Three different car alarms are going off outside my building all at once. Did I miss an earthquake?

— Kate (@heyescapist) August 20, 2013

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.