My, What Big Claws! Dino Talons Used for Digging

Giant, razor-sharp claws seen on herbivorous dinosaurs may have been used for digging, grasping or piercing, a researcher says.

The new findings shed light on the changes in claw form and function that occurred as birds evolved from their ancient dinosaur ancestors, the scientist added.

Meat-eating dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor were all reptiles known as theropods; they relied on sharp teeth and claws to capture and kill prey. Many theropods may have possessed feathers, and research suggests modern birds evolved from these dinosaurs. [In Images: The Life of T. Rex]

However, not all theropods were carnivores.

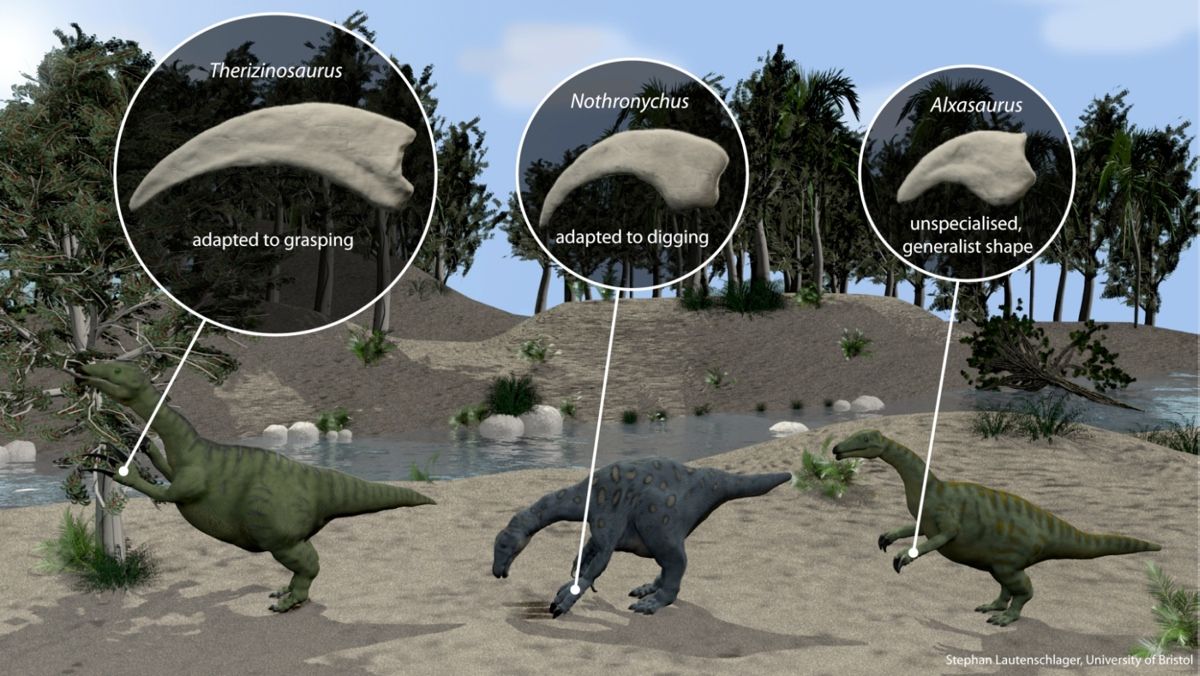

"The stereotypical image of theropod dinosaurs is that of large, predatory and carnivorous animals," said study author Stephan Lautenschlager, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Bristol in England. "However, fossil findings in the last 15 to 20 years have shown that a number of different groups among theropods did not conform to this classical view. Many of these had apparently adapted to a different diet and become omnivores or herbivores — that is evident from the shape of the teeth and the morphology of the skull."

Lautenschlager investigated an unusual group of theropods known as therizinosaurs, which lived between 66 million and 145 million years ago in Asia and North America. These long-necked dinosaurs, which possessed coats of primitive downlike feathers, could reach up to 23 feet (7 meters) long with massive, razor-sharp claws more than 19 inches (50 centimeters) in length.

"The large claws of Therizinosaurus cheloniformis have been enigmatic since they were first discovered in the 1950s," Lautenschlager said. "Originally it was thought they belonged to some sort of giant turtle. Later it became clear that they belonged to the group of dinosaurs known as therizinosaurs, and that other members of this group also had enlarged claws."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, despite gigantic claws that might seem like ideal weapons for killing prey, therizinosaurs were herbivores. To understand how these plant eaters might have used their claws, Lautenschlager digitally scanned the claws of 65 theropod species and generated computer models to simulate how the dinosaurs might have used such talons. He also compared those reptile talons with claws from 40 mammal species, which scientists know the function of.

Lautenschlager discovered therizinosaurs may have used their giant claws for digging, grasping or piercing.

"The grasping function can roughly be compared with a rake or grappling hook," Lautenschlager said. "These claws were probably used to grasp a branch and pull it closer to the animal to reach parts of the vegetation otherwise out of reach." The dinosaurs may have used digging claws to unearth tasty roots.

Lautenschlager noted the changes seen in therizinosaur claws paralleled changes seen in their skulls and teeth that helped the animals adapt to changes in what they ate. This suggests changes in theropod diet were major drivers for skeletal changes in theropod evolution.

These findings might shed light on the evolution of modern birds from ancient theropods.

"Therizinosaurs were not directly ancestral to birds," Lautenschlager said. "Nevertheless, by understanding how different dinosaurs adapted to different ecological situations — for example, different food — we can better understand what changes in the skeleton were related to diet, to flight or something completely different."

Lautenschlagerdetailed his findings online May 7 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.