Oldest Known Petrified Sperm Found — and It's Huge!

The oldest petrified sperm ever discovered is gargantuan, at least for a gamete.

The sperm comes from the early Miocene epoch, between about 23 million and 16 million years ago, and belonged to a tiny crustacean called a seed shrimp or ostracod. Seed shrimp are bivalves like muscles, but sport tiny appendages that make them look like walking beans. Though they measure just millimeters long, their sperm often reaches more than 0.4 inches (1 centimeter) in length.

The new fossilized sperm comes from an ancient cave deposit in Australia, where bat guano falling into the water may have helped preserve the cells.

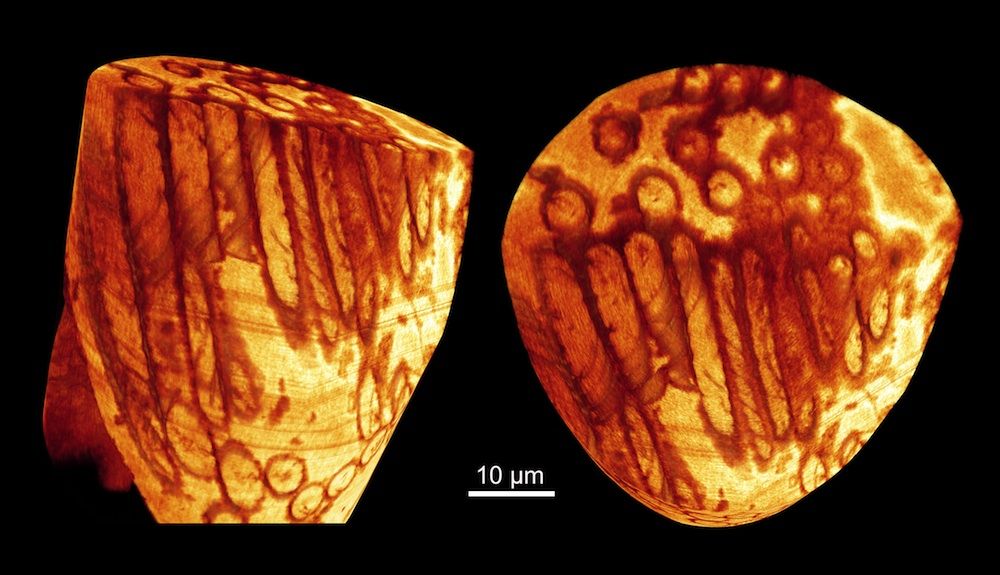

"We can distinguish the typical helical organization of the organelles in the sperm cell, which makes its surface look like a hawser or cable," study researcher Renate Matzke-Karasz, a geobiologist at Ludwig-Maximilian-University in Germany, said in a statement. "But the most astounding aspect of our findings is that it strongly suggests that the mode of reproduction in these tiny crustaceans has remained virtually unchanged to this day." [See images of the giant sperm and ancient ostracods]

Ancient animals, strange sperm

Seed shrimp aren't the only organisms with absurdly long sperm. The longest sperm in nature today belongs to Drosophila bifurca, a fruit fly whose seed stretches to more than 2 inches (5 centimeters).

But ostracod sperm is extra odd, because it lacks the familiar tail, or flagellum, that propels most sperm cells. Instead, ostracod sperm consists of a large, elongate head. This entire structures moves by contracting organelles along its membrane, which causes the sperm cell to ripple and rotate.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Matzke-Karasz and her colleagues discovered the fossilized sperm cells in five specimens of ostracods from the Riversleigh fossil site in northwest Queensland, Australia. This site preserves what was once a cave, with copious ancient bat bones and cave formations. Ostracods once lived in standing water inside the cave.

The sperm are at least 16 million years old and fossilized in rock, making them the oldest petrified sperm cells ever discovered. (The previous oldest-known ostracod sperm was only a few thousand years old.) One other sperm find does beat out the ostracod find in age: An insect-like springtail trapped in amber about 40 million years ago had sperm inside its body. But preservation in amber is different than preservation in rock, as amber frequently preserves soft tissue and rock rarely does.

Giant sperm

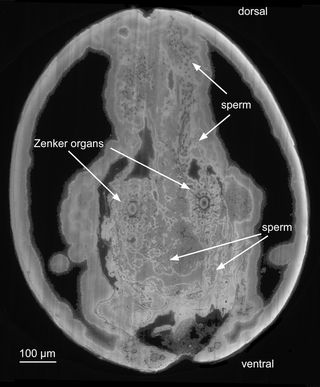

Matzke-Karasz and her colleagues studied 66 ostracod fossils from the Queensland site using X-ray tomography, which enables a three-dimensional peek inside the fossils.

In 2009, Matzke-Karasz and her team discovered a 100-million-year-old female ostracod with large receptacles for giant sperm, but the cells inside had degraded. The new study proved more fruitful. The researchers discovered sperm cells in various states of preservation in one male and three female ostracods of the species Heterocypris collaris, and one female of the species Newnhamia mckenziana.

The researchers could not discern the length of the sperm in all of the fossils, but the researchers estimate that the 0.05-inch-long (1.26 mm) H. collaris male had sperm almost exactly its own length — 0.047 to 0.051 inches long (1.2 to 1.3 mm).

The fossils also preserved the ducts in the female ostracod anatomy where the sperm would enter the body. These spiral ducts are longer even than ostracod sperm, sometimes reaching lengths four times that of the ostracod body. The discovery of the giant sperm and giant receptacle ducts provides evidence that these body parts co-evolved and have changed little in millions of years, the researchers report today (May 13) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

"This suggests that their mode of reproduction represents a functionally successful model," Matzke-Karasz said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.