The Beautiful New Jellyfish Identified in the Gulf of Venice

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

A bloom of new jellyfish started appearing in the Gulf of Venice last autumn. They were first detected by a fisherman from Chioggia in north-east Italy when hundreds of the beautiful yellow species filled his nets. News of this reached my team at the University of Salento’s MED-JELLYRISK and VECTORS projects through a citizen-science initiative we run that gets locals to report jellyfish sightings along the Italian coasts.

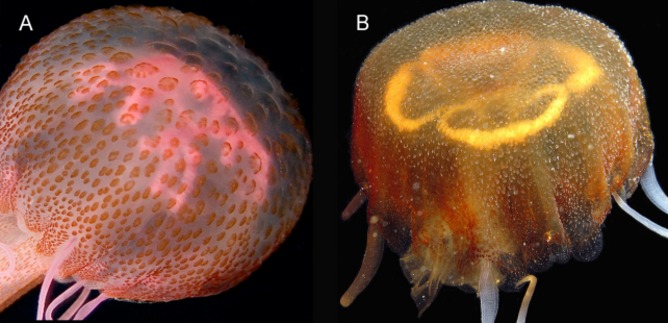

When photos of the new jellyfish started to filter through, it was immediately clear that we were dealing with a previously undescribed species. To an expert eye, the differences were manifest. The white horseshoe-shaped, ribbon-like gonads, the yellow-ochre colour of the jellyfish umbrella, the pronounced warts on its surface and the long and delicate, transparent arms were distinctive elements. They altogether indicated the jellyfish was something new to any species that’s previously been categorised.

Manifold differences

To investigate further, I asked colleagues from the Chioggia marine station to collect and send me some specimens. As well as being able to describe the anatomical features more distinctively and accurately, we carried out molecular analyses to confirm the jellyfish belonged to a new species within the genus Pelagia. This involved DNA barcoding, which compares short sequences of the jellyfish’s DNA with other, similar, species. It works like the barcode sequence of stripes commercially adopted by supermarket scanners to rapidly distinguish between different products.

The new species bears similarities to the Pelagia noctiluca, also known as the mauve stinger for its purple glow and stinging abilities. But there are visible and genetic differences, and the species is distinct from other species contending to be part of the Pelagia species recorded from other areas of the world. This is why we’ve dubbed it the Pelagia benovici.

New kid on the block

The most interesting issue is that the North Adriatic sea is one of the most investigated areas of the world as there are several marine stations in the area. This means that it is impossible for such a conspicuous jellyfish with large population numbers to have remained unnoticed until now. It would hardly be more remarkable to discover a new chimp species in London’s Hyde Park.

Clearly, this jellyfish has been involuntarily introduced by humans. The Gulf of Venice is a renowned hotspot for bioinvasions in the Mediterranean Sea, which are often brought about through the ballast water of ships or when harvested species are transported for aquaculture purposes and additional, unwanted alien species are carried along with them.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Managing their impact

Invasive species can have a large impact on the environment they are entering. It’s hard to say what the exact impact of the new Pelagia benovici will be, as our knowledge of it is still limited and our efforts have so far focused on identifying it. But, in general, non-indigenous species can affect the biodiversity and functioning of an ecosystem, potentially displacing or threatening native species with key roles.

Human activities can also be impaired by new species, where they find suitable conditions to proliferate. They can cause the collapse of fisheries, as happened in the 1980s in the Black Sea, after the introduction of a voracious comb jellyfish. Tourism may also be affected, when stinging species arrive.

This was the case with the large Rhopilema nomadica jellyfish that entered the Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal over 20 years ago. In 2011, outbreaks of Rhopilema clogged the cooling pipes of a coastal power plant, forcing energy shutdown in Tel Aviv. Similarly, a nuclear power plant was shut down in Scotland in 2011 and Sweden in 2013 by outbreaks of the moon jellyfish, Aurelia aurita in the North Sea.

Our MED-JELLYRISK project is planning strategies to minimise the impact of jellyfish on human activities like tourism and fishing, as well as health. As more jellyfish are spotted and new species emerge, we are testing out anti-jellyfish nets and how to create safe swimming zones in areas where they find best conditions to proliferate.

Reports of the Pelagia benovici have dried up in the last couple of months, but jellyfish are erratic – they can be present in their millions, disappear and then suddenly come back. Our citizen science projects will help keep tabs on them and we are currently extending them to include all the countries around the Mediterranean with its diverse, ever-changing sea life.

Stefano Piraino has received research funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) for the VECTORS project and from the ENPI CBCMED programme for the MED-JELLYRISK project. Additional technical and logistic support and use of facilities was obtained from the FP7 EU projects COCONET and PERSEUS, and from the Italian project RITMARE.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.