Rare Sight: Colorado River Reaches Gulf (Photos)

For the first time in 16 years, freshwater from the Colorado River has flowed into the salty waters of the Gulf of California.

On Thursday (May 15) a high tide surged past a stubborn sandbar and connected the river with the Sea of Cortez, said Francisco Zamora, director of the Colorado River Delta Legacy Program for the Sonoran Institute. Because of water use upstream, little flow from the 1,450-mile Colorado River [2,330 kilometers] has reached the sea in 50 years.

Zamora watched the high tides make the final link between river and sea last week via a pilot channel dug by the Sonoran Institute to increase freshwater flow into the Gulf of California. (The freshwater comes from agricultural runoff and releases from wastewater treatment plants.) The seawater ran north through the Rio Hardy, a series of swampy wetlands and mudflats that drains 15 miles (24 km) downstream into Gulf waters. [Images: Colorado River Connects With Sea]

The reunion is the end of a 53-day journey for the long-planned Colorado River pulse flow, an artificial flood meant to restore the river's parched delta. The water comes from an international agreement called Minute 319. The plan allocates about 1 percent of the river's flow to a five-year experiment that will mimic spring floods in the delta. The goal is bring back the plants and animals that once thrived in the river's outlet.

When the pulse flow was unleashed on March 23 from the Morales Dam, scientists didn't know if the water would enter the Gulf, or remain in the river's broad delta. Seeing the Colorado complete its journey broadens the project's restoration potential, Zamora said.

"After waiting for two months, it was very exciting to see," Zamora told Live Science's Our Amazing Planet. "This pulse flow opens the door for new possibilities for restoring riparian and estuary habitats."

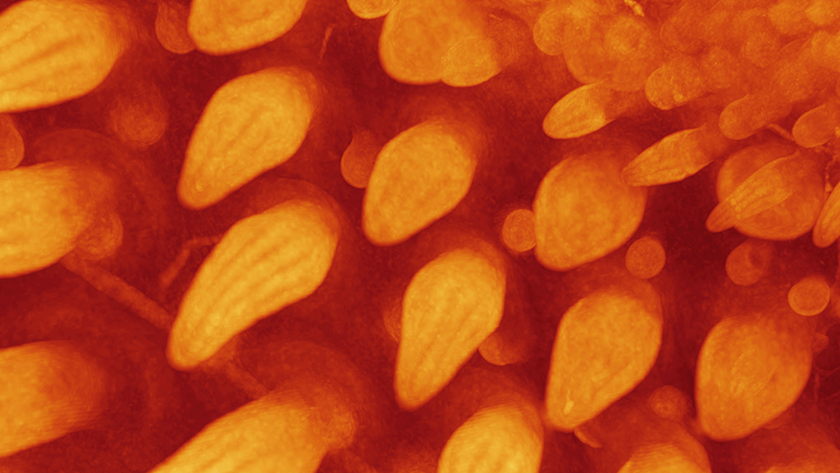

While much of the delta is choked with salt-loving tamarisk (an invasive salt cedar) now, conservationists hope to see more riparian habitat growing after the pulse flow: cottonwood and willow forests, along with wetlands thick with cattail marshes. The flood was timed for the spring seed release from these trees, to provide moist ground for seedlings.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After the flood ends, a lower-level "base flow" will continue through 2017 to rehydrate several restoration sites in the delta.

Though the amount of water reaching the estuary habitat, where river mixes with sea, will likely be small, Zamora said it could help the hundreds of bird species who nest in the Gulf, and perhaps even restore some species that had vanished from the estuary.

"I think everyone is very excited about the opportunities," Zamora said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.