My 1975 'Cooling World' Story Doesn't Make Today's Climate Scientists Wrong

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Inside Science Minds presents an ongoing series of guest columnists and personal perspectives presented by scientists, engineers, mathematicians, and others in the science community showcasing some of the most interesting ideas in science today.

(Inside Science) – "The central fact is that, after three quarters of a century of extraordinarily mild conditions, the Earth seems to be cooling down. Meteorologists disagree about the cause and extent of the cooling trend, as well as over its specific impact on local weather conditions. But they are almost unanimous in the view that the trend will reduce agricultural productivity for the rest of the century." – Newsweek: April 28, 1975

That's an excerpt from a story I wrote about climate science that appeared almost 40 years ago. Titled "The Cooling World," it was remarkably popular; in fact it might be the only decades-old magazine story about science ever carried onto the set of a late-night TV talk show. Now, as the author of that story, after decades of scientific advances, let me say this: while the hypotheses described in that original story seemed right at the time, climate scientists now know that they were seriously incomplete. Our climate is warming -- not cooling, as the original story suggested.

Nevertheless, certain websites and individuals that dispute, disparage and deny the science that shows that humans are causing the Earth to warm continue to quote my article. Their message: how can we believe climatologists who tell us that the Earth's atmosphere is warming when their colleagues asserted that it's actually cooling?

Well, yes, we should trust them, despite the views of detractors such as comedian Dennis Miller, who brought my story to The Tonight Show in 2006. Several atmospheric scientists did indeed believe in global cooling, as I reported in the April 28, 1975 issue of Newsweek. But that was then.

In the 39 years since, biotechnology has flowered from a promising academic topic to a major global industry, the first test-tube baby has been born and become a mother herself, cosmologists have learned that the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate rather than slowing down, and particle physicists have detected the Higgs boson, an entity once regarded as only a theoretical concept. Seven presidents have served most of 11 terms. And Newsweek has become a shadow of its former self.

And on the climate front? The vast majority of climatologists now assure us that Earth's atmosphere is not cooling. Rather it's warming up. And the main responsibility for the phenomenon lies with human activity.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There's no serious dispute any more about whether the globe is warming, whether humans are responsible, and whether we will see large and dangerous changes in the future – in the words of the National Academy of Sciences – which we didn't know in the 1970s," said Michael Mann, a climatologist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. He added that nearly every U.S. scientific society has assessed the evidence and come to the same conclusion.

The recent National Climate Assessment takes an equally emphatic view.

"What is new over the last decade is that we know with increasing certainty that climate change is happening now," it states. "While scientists continue to refine projections of the future, observations unequivocally show that climate is changing and that the warming of the past 50 years is primarily due to human-induced emissions of heat-trapping gases."

I'm sure it's clear by now that I accept the views of the National Academy, National Climate Assessment, Mann, and the huge majority of his fellow climatologists. Nevertheless, websites devoted to denying the existence of human-caused climate change – or at least promoting the idea that nothing should be done about it – continue to use my article to validate their thinking. In fact the article has reportedly become the most-cited article in Newsweek's history.

Those that reject climate science ignore the fact that, like other fields, climatology has evolved since 1975. The certainty that our atmosphere is indeed warming stems from a series of rigorous observations and theoretical concepts that fit into computer models and an overall framework outlining the nature of Earth's climate.

These capabilities were primitive or non-existent in 1975. In fact my report reflected a real strand of climatological thinking back then. I was far from the only science writer to cover the possibility of global cooling. Time, Science News, and the New York Times, among other media outlets, wrote about it, because some climate scientists had genuine reasons to believe that the global climate might be cooling and had published scholarly papers on the matter.

Speaking personally, though, I accept that I didn't tell the full story back then. Indeed, the issue raises questions about the relationship between science writers and scientists as well as the attitudes toward science of individuals with political agendas.

"Three independent strands of science at the time got conflated in the articles: analyses of direct temperature data that showed a decline in temperatures particularly over the Northern Hemisphere since the 1940s; a very high level of pollution by sulfate aerosols that cooled the planet; and evidence that the timing of ice ages was caused by wobbles in Earth's orbit," explained Gavin Schmidt, deputy chief of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, in New York. Indeed, he added, "some parts of the article are OK even today."

At the same time, however, evidence had emerged of increases in the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide, a gas known to warm the atmosphere.

"The science was sort of speculative [in 1975]," Mann recalled. "A National Academy of Sciences report concluded there wasn't enough information at that particular time because we had two competing forces – aerosols and greenhouse gases. It wasn't entirely clear which would win out."

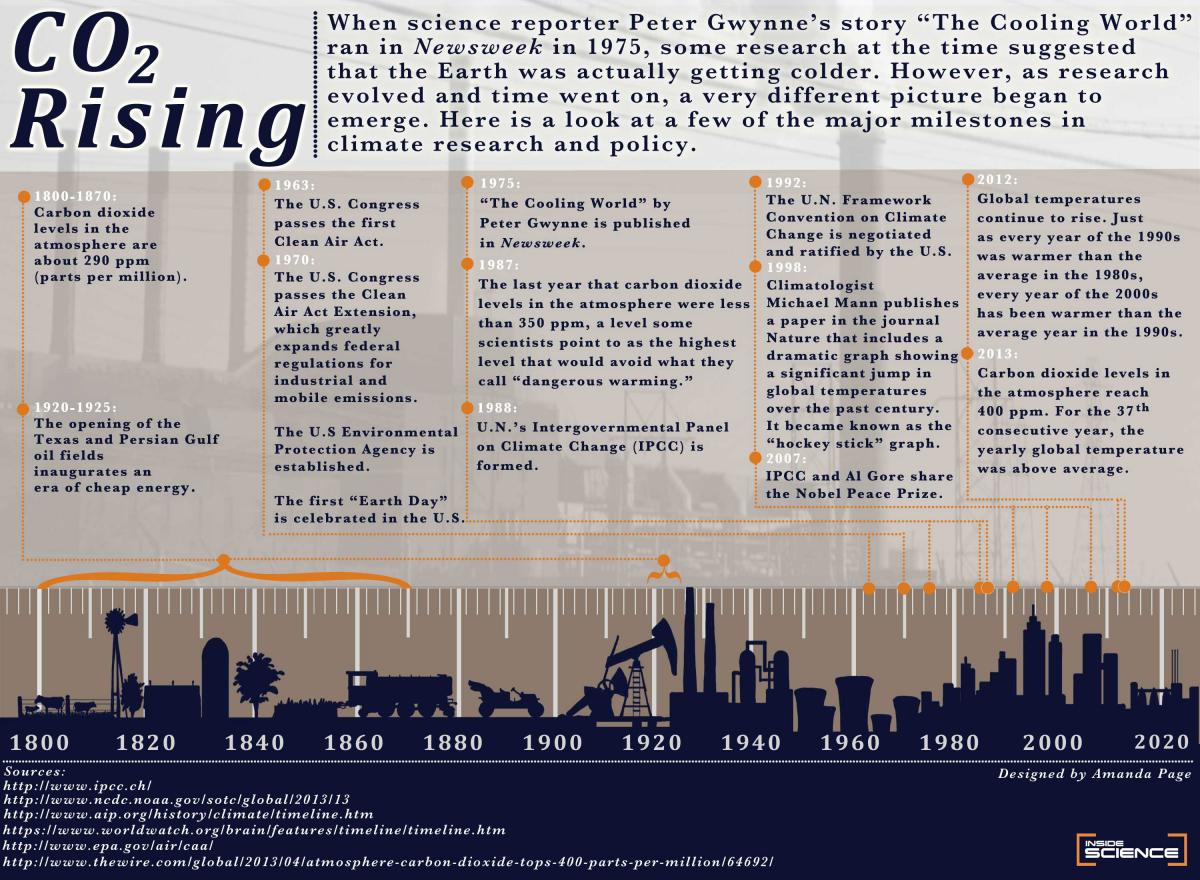

Ironically, efforts to clean up the atmosphere made it possible to resolve the scientific mystery and convince climatologists that human activity is warming the planet. Policy actions such as the Clean Air Act of 1970 in the United States and similar initiatives in other countries aimed to reduce the amount of sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere. Since those compounds primarily reflect heat, their reduction effectively gave carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases more control over the Earth's temperature.

NASA scientist James Hansen was the first to sound the alarm. In 1988, he pointed out that a sort of Faustian bargain had cleaned up the atmosphere but at the cost of worsening the greenhouse problem.

Hansen and other climatologists began to develop models of the climate which showed the influence of human activity, via the burning of fossil fuels, on global temperatures.

Observations and analyses since then have confirmed and strengthened the models and the broad understanding of climate change, along with the portion that's due to human activity. Richard Somerville, a climate scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the University of California, San Diego, summarized the findings in an email.

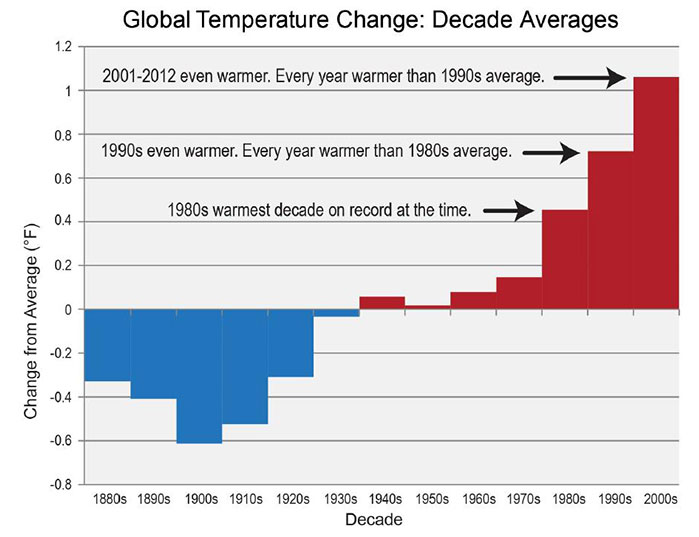

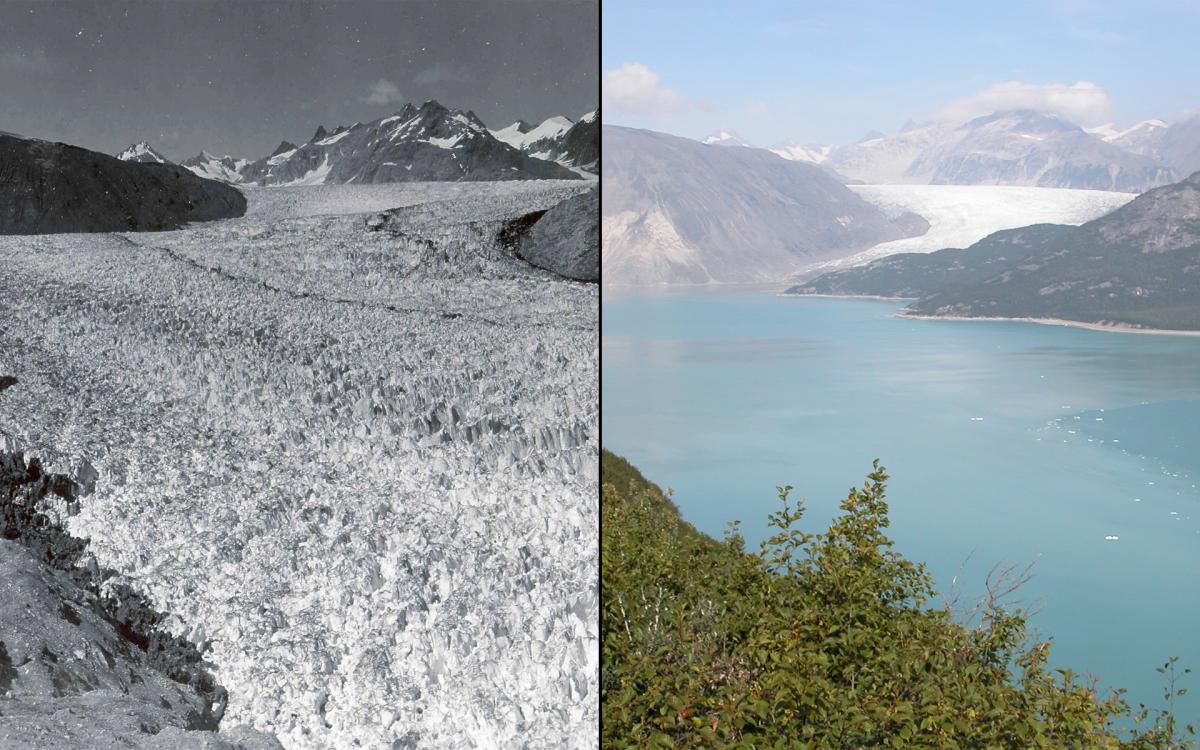

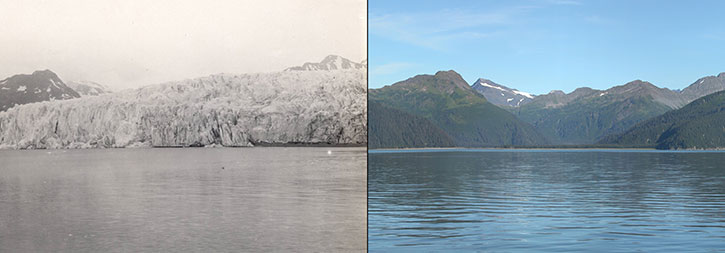

"There are many lines of observational evidence that the world is warming, including globally rising air and ocean temperatures, retreating glaciers worldwide, increasing sea level, decreasing Arctic Sea ice extent, and mass loss on the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica," he wrote. "In addition, an entire new body of climate science called 'detection and attribution' convincingly shows that the observed climate changes have distinctive space-time patterns that are consistent with causes due to human activities."

The counterattack had started by the beginning of the 1990s. The purported evidence against global warming included the news articles on cooling by myself and others.

Some commentators, such as Dixy Lee Ray, former chair of the Atomic Energy Commission, asserted that the articles represented climate scares that inevitably turned out to be untrue – as would the idea of global warming, they asserted.

Others took a less subtle route. The articles proved, they argued, that the atmosphere was cooling and that there was no reason to change that conclusion. In that view, climate science never changes.

However, both types of warming deniers, along with policymakers who have consistently opposed any regulation designed to reduce acid rain, the destruction of the ozone layer, and other perceived ills, have consistently used the articles – particularly mine – as ammunition.

But that's just one line of attack. Mann suffered another starting in 1998, after he published an article in the journal Nature; that included a "hockey stick" model that demonstrated a dramatic increase in the rate of recent global warming.

"I was at the receiving end of the attacks from many of the same individuals, think tanks, and organizations implicated in past attacks on other climate scientists, such as [late] climatologist Steve Schneider," he wrote in an email. "The attacks on climate science and on me specifically have escalated for a simple reason: As the scientific evidence becomes clearer and the threat becomes clearer, it takes yet more disinformation and propaganda to obscure the truth. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent by fossil fuel interests seeking to muddy the waters. That has, in turn, provided cover for politicians doing their bidding in opposing any attempts to regulate carbon emissions."

Opponents of Mann and his fellow climatologists also seek to highlight areas of disagreements among climatologists. Certainly those disagreements exist. But they don't affect the reality that human activity is the primary trigger of warming in recent decades.

Take, for example, research on the relationship between climate change and extreme weather.

"It is a very nuanced subject, and a legitimate controversy," Mann said in an interview. "There really are different schools of thought, each of which are credible and making arguments in good faith. Jennifer Francis at Rutgers argues that there is a connection with loss of sea ice, and others are skeptical."

Schmidt agrees.

"It is a genuine debate," he said. "Scientists don't just sit around congratulating ourselves on what we've done. We look for things at the cutting edge between known and unknown. It's a complex terrain and that's what makes it interesting."

Certainly, the disputes have become more nuanced. But their existence provides opponents of scientific findings that they find unpopular with opportunities to muddle the facts.

"The American political system has always had a rather odd connection to the role of expertise," Schmidt added. "There's a clear strand in American discourse that is anti-intellectual and anti-expertise."

While the affair reveals much about the relationship between politics and science, it also casts a shadow on science writing.

"There's too much handwaving in science journalism," Schmidt noted. "Scientists don't spend a lot of time when talking to journalists about what their research doesn't mean. One of the fault lines between science and journalism is how you pull together the bigger picture. So a reticence on the part of scientists to fill in the big picture, and over-enthusiasm on the part of journalists to say what does it all mean, means that the journalists don't get it quite right."

Here I must admit mea culpa. In retrospect, I was over-enthusiastic in parts of my Newsweek article. Thus, I suggested a connection between the purported global cooling and increases in tornado activity that was unjustified by climate science. I also predicted a forthcoming impact of global cooling on the world's food production that had scant research to back it.

The messages for science writers are to ask questions beyond the obvious and to seek out what the science doesn't imply as well as what it does. If I had applied those lessons back in 1975, I might not now be in the embarrassing position of being a cat's paw for denial of climate change.

Over my career I've covered subjects as diverse as cell biology, the world of physics a century after Einstein's birth, space commerce, and World Cup soccer. I've won prizes for my writing, including a lifetime award from the American Chemical Society. But I fear that my obituary will be dominated by that single article in Newsweek.

This story was provided by Inside Science News Service. Peter Gwynne is a freelance science writer based in Sandwich, Massachusetts, and a frequent contributor to Inside Science. He is the author of "The Cooling World," which appeared in Newsweek in April, 1975.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus