Extinction Rates Soar to 1,000 Times Normal (But There's Hope)

Species on Earth are going extinct at least 1,000 times faster than they would be without human influence, new research finds. But there's still time to save the world from this biodiversity disaster.

Between 100 and 1,000 species per million go extinct every year, according to the new analysis. Before humans came on the scene, the typical extinction rate was likely one extinction per every 10 million each year, said study researcher Stuart Pimm, a Duke University biologist.

These numbers are a big increase from the previous estimates, which held that species were going extinct 100 times faster than usual, not 1,000 times faster or more, Pimm told Live Science. But despite the bad news, he said, his research is "optimistic." New technology and citizen scientists are allowing conservationists to target their efforts better than ever before, he said. [Biodiversity Threats: See Maps of Species Hotspots]

"Although things are bad, and this paper shows that they're actually worse than we thought they were, we are in a much better position to do something about that," Pimm said, referring to the study published today (May 29) in the journal Science.

Understanding extinction

Pimm and his colleagues have long worked to understand the effect of humanity on the rest of the species that share the planet. In the history of life on Earth, five mass extinctions have wiped out more than half of life on the planet. Today, scientists debate whether humanity is causing the sixth mass extinction.

This question is trickier than it may seem. Certainly, humans have driven species from the dodo to the Tasmanian tiger to the passenger pigeon to extinction. There's no doubt that continuing deforestation and climate change will destroy even more species, including some humanity will never get the chance to discover. But researchers don't even know for sure how many species exist on the planet. About 1.9 million species have been described by science, but estimates as to how many are out there range from 5 million to 11 million.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Knowing how many species go extinct without human influence is another challenge. The fossil record, after all, is frustratingly incomplete. To get an estimate rooted in science, Pimm and his colleagues used data from molecular phylogeny, which uses DNA information to build a web of relationships between species. Phylogenic trees can show how quickly species diversified. And because species don't normally go extinct faster than they diversify to form new species, these trees give a sense of the upper limit of normal extinction rates. By this method, the researchers arrived at the background estimate of one extinction per 10 million species per year. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

Humanity's great extinction?

Next, the researchers looked at modern extinction rates. They tracked animals known to science, calculating how long they tended to survive after discovery (or if they are still extant). These rates brought them to the estimate of 100 extinctions or more per million species each year — which did not come as a great surprise.

"It's not a good thing, because it's higher than it was before, but for the community that focuses on these things, we kind of knew where it was headed," said study researcher Clinton Jenkins, a conservation researcher at the Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas (IPÊ) in Nazaré Paulista, Brazil.

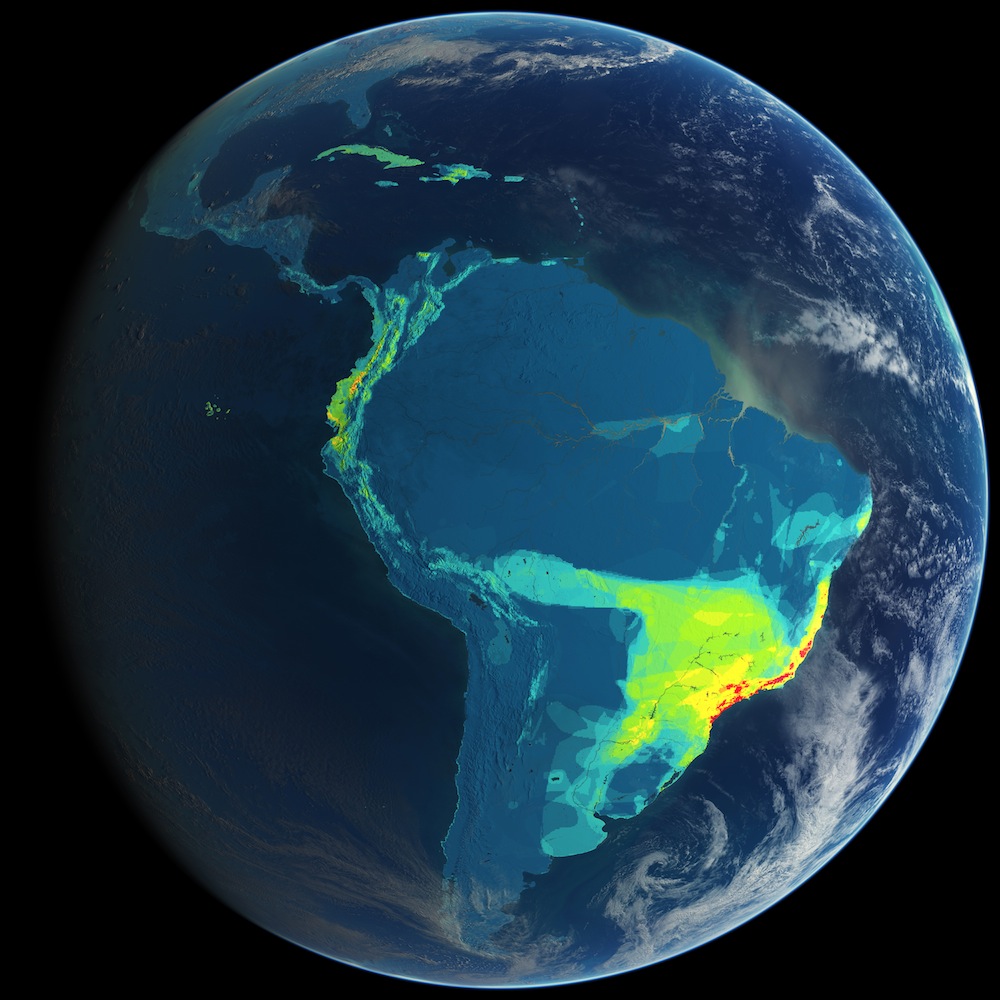

But, Jenkins and Pimm agreed, there is hope. The most endangered species tend to be ones with small ranges in threatened areas, Jenkins told Live Science. Many are in countries without many resources to protect them, but the ability of scientists to track and understand the threats has never been better. Satellite imagery and global tracking of deforestation can reveal habitat loss in near-real time. And websites like biodiversitymapping.org (created by Jenkins) reveal biodiversity hotspots for birds, mammals, amphibians and more.

"It's probably less than 10 percent [of land area] that has most of the species we're really at risk of losing," Jenkins said. "So if we focus on those areas, it can solve most of the problem."

Citizen scientists can help, too, the researchers said. Smartphone cameras enable people to go out, snap photos of organisms and report their findings to conservation groups. Pimm and Jenkins both recommend iNaturalist, which began as a master's project by graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley. The site allows users to upload photos of plants and animals, tagging them with the location of the sighting and the likely species, which other users then confirm. The site is linked to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List, which tracks threatened species.

Jenkins uses the site himself. For example, in April, he noticed a group of stripy-tailed primates scurrying around the trees near his home in Nazaré Paulista. He went outside with a pair of binoculars and a smartphone and snapped some photos, which he uploaded to iNaturalist. Other users quickly confirmed that his neighbors were buffy-tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix aurita), which the IUCN Red List categorizes as a vulnerable species.

"Within the same day, that picture was on the Red List page of that species as an example," Jenkins said.

Such citizen observations can help define species' ranges and numbers, which are often out of date in the scientific literature. That data, in turn, can reveal whether conservation projects are working and what areas are at risk, the researchers said.

"People often say that we are in the middle of the sixth mass extinction," Pimm said. "We're not in the middle of it — we're on the verge of it. And now we have to tools to prevent it."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.