How Twisted Was King Richard III's Spine? New Models Reveal His Condition

Shakespeare called him a hunchback, but a new three-dimensional model of King Richard III's spiraling spine shows his true disability: adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.

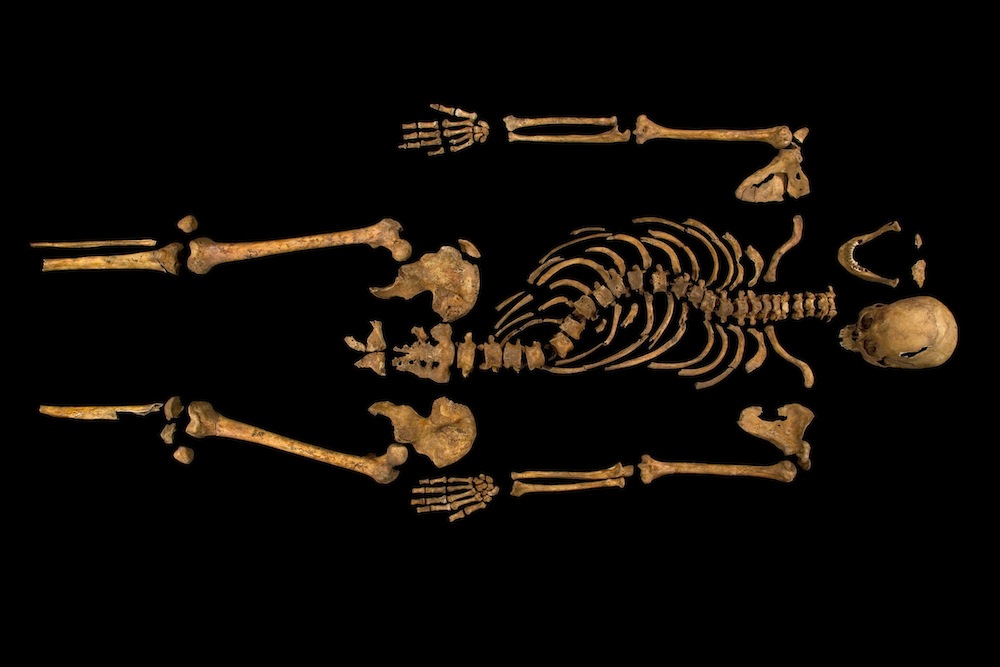

Richard III, who ruled England from 1483 to 1485, died in the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. His body was buried in a hastily dug grave in Leicester, where it was then lost to time. In 2012, archaeologists rediscovered the bones under a city council parking lot, and exhumed them for study.

The curve in Richard's spine was immediately obvious, confirming an anatomical anomaly that had long been controversial. No paintings made during the king's lifetime survive, according to the Richard III Society (though some exist from soon after his death that were likely copied from originals, and modern researchers have reconstructed the king's face). The popular image of Richard III came from Shakespeare, who describe the king as a "poisonous bunch-backed toad" in his 1593 play. Shakespeare's Richard III had a hunchback and a withered arm, and modern historians were uncertain whether the depiction held any truth or was simply designed to please the political enemies of the king's Plantagenet family line. [Gallery: The Spine of Richard III]

Medical history

In 1490, just five years after Richard's death in battle, however, medieval historian John Rous described the king as a small man with "unequal shoulders, the right higher and the left lower." This description is consistent with scoliosis, a condition in which the spine curves sideways.

Richard III's rediscovered skeleton revealed that the king did, in fact, have scoliosis. Now, researchers led by University of Leicester bioarchaeologist Jo Appleby reveals the details of his condition.

Appleby and her colleagues conducted computed tomography scans of the king's individual vertebrae. These CT scans use X-rays to image the inside of the bone, creating virtual slices that can be explored digitally. Using the scans, the researchers then created polymer copies of each vertebra, piecing them together into a 3D model of Richard III's spine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Model ruler

The scans and model showed that Richard III had a right-sided, spiral-shaped curve that peaked at thoracic vertebrae 8 and 9, approximately at his mid-back. The curve was well-balanced, meaning that Richard III's spine got back in line by the time it hit his pelvis. As a result, his hips were even, the researchers report today (May 29) in the journal The Lancet. Richard III would not have limped or had trouble breathing due to his condition, which are common side effects of severe scoliosis. [Images: New Dig at Richard III's Rediscovered Grave]

"Obviously, the skeleton was flattened out when it was in the ground," Appleby said in a statement. "We had a good idea of the sideways aspect of the curve, but we didn't know the precise nature of the spiral aspect of the condition."

Scoliosis can be caused by muscular imbalances that pull the spine out of alignment, but the rest of Richard III's skeleton showed no evidence of such problems, Appleby and her colleagues found. Nor were there any malformed hemivertebrae, which are wedge-shaped vertebrae that can cause the spine to twist and turn.

Instead, the researchers concluded, Richard III likely had adolescent-onset idiopathic scoliosis. Idiopathic means the cause is unknown, which is the case in the majority of people with scoliosis. The abnormal curve probably appeared in Richard after age 10.

The curve itself had a spiral appearance, and an angle that would be considered large today. Doctors use a measurement called the Cobb angle to gauge spine deformity. On an X-ray, they draw a line outward from the top of the highest vertebra on the curve and then do the same for the bottom of the lowest vertebra. They then measure the angle where the two lines meet. Richard III's Cobb angle was between 70 degrees and 90 degrees in life, the researchers determined.

Without scoliosis, Richard III would have stood about 5 feet, 8 inches (1.7 meters), average for a medieval European man. The curvature would have taken a few inches off his height, and it would have caused the shoulder imbalance that Rous described. Nevertheless, it would not have kept Richard III from being an active individual, Appleby said.

"The condition would have meant that his trunk was short in comparison to the length of his limbs and his right shoulder would have been slightly higher than the left," she said, "but this could have been disguised by custom-made armor and by having a good tailor."

Though scientists can't be sure whether or not Richard III underwent any treatment for his scoliosis, Mary Ann Lund of the University of Leicester said painful traction was widely available at the time. Not only would Richard have been able to afford traction, but also, Lund found, his doctors would have been well aware of the method, as the 11th-century polymath Avicenna described such traction in treatises on medicine and philosophy.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.