Latest Game Consoles Suck Up Electricity, Even at Rest

Pierre Delforge is director of the High Tech Sector Energy Efficiency program at NRDC. This Op-Ed was adapted from a post to the NRDC blog Switchboard. Delforge contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

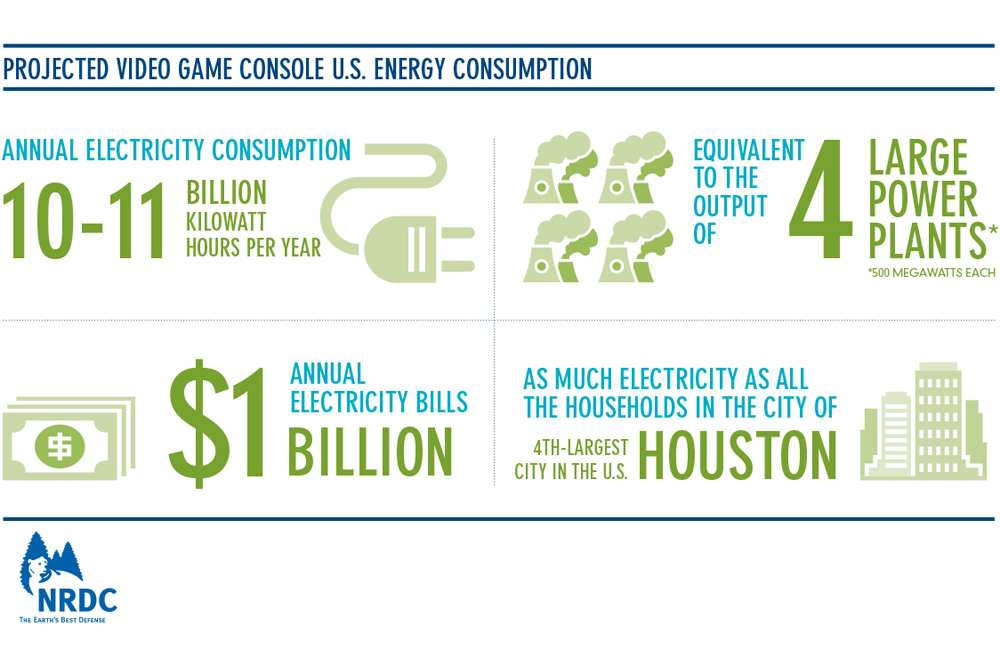

The latest game consoles — Sony PlayStation 4, Microsoft Xbox One and Nintendo Wii U — are on track to consume as much electricity in the United States each year as all the homes in Houston, the fourth-largest city in the country, and cost U.S. consumers more than $1 billion to operate annually.

Unfortunately, much of that energy will be consumed when gamers are asleep.

Those findings are in NRDC's new study, “The Latest-Generation Video Game Consoles: How Much Energy Do They Waste When You’re Not Playing?,” which was released May 16. As video games have become a facet of life in the United States, with many people playing games on a daily basis, it is increasingly important to ensure the consoles don't waste large amounts of energy while still delivering the performance and functionality that users expect.

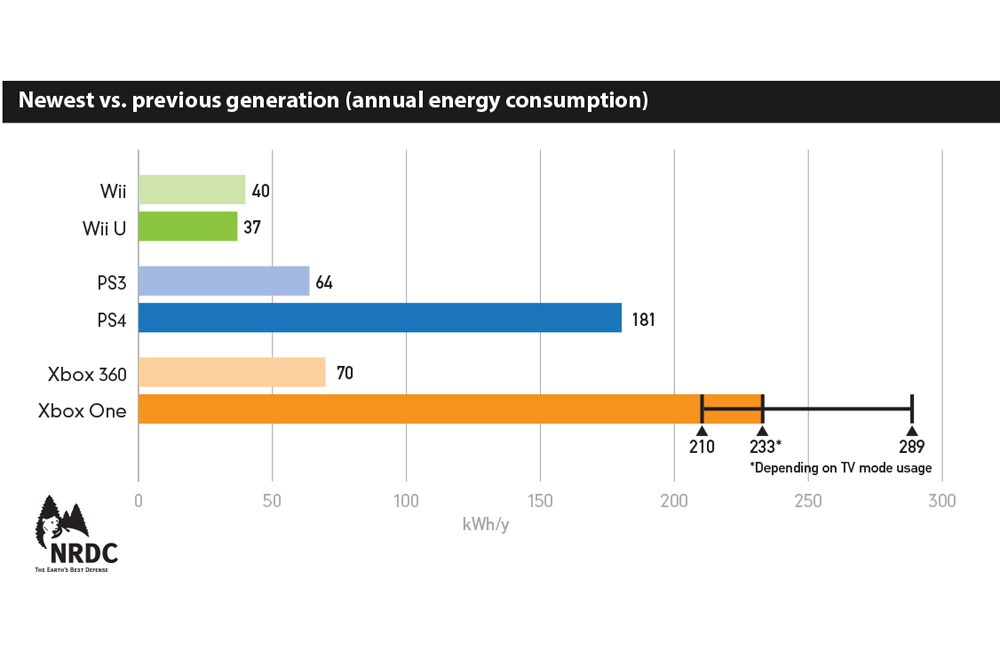

As a follow-up to our 2008 report on the energy use of video game consoles, NRDC performed extensive laboratory tests on the latest-generation consoles. We found that while they have incorporated many energy-saving features into their designs and offer greater performance, the Sony PS4 and Microsoft Xbox One consume two to three times more annual energy than the most recent models of the previous generation.

However, the Wii U consumes less energy than its predecessor the Wii, despite providing higher definition graphics and processing capabilities, in large part thanks to its very low power in "connected standby mode." [New Device Gets a Better Grip on Gaming ]

Key findings from the study

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After testing the devices and analyzing the data, we made the following observations regarding the consoles' features and energy use.

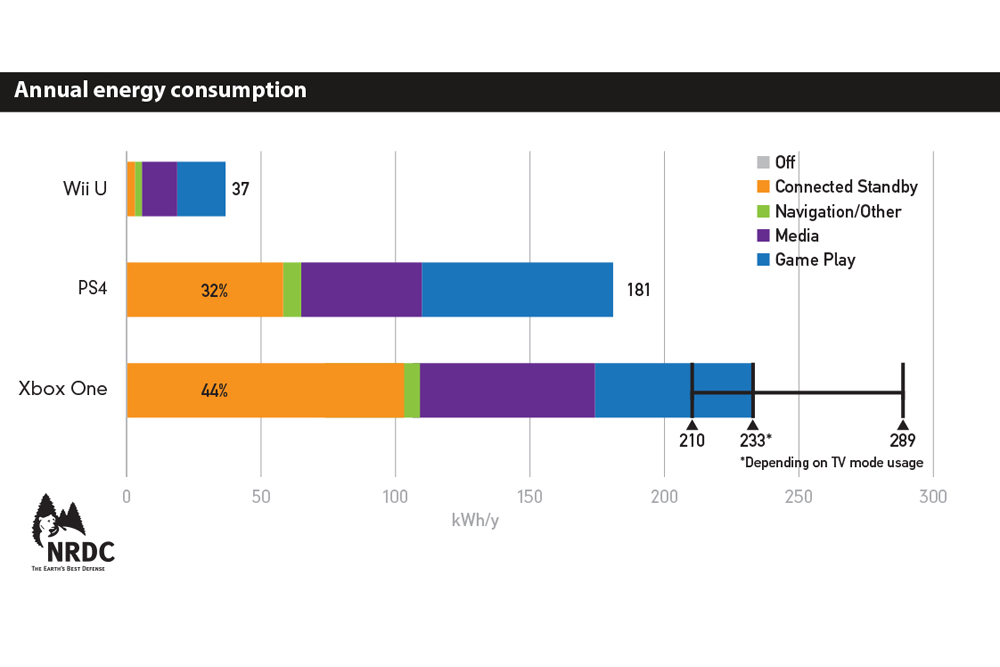

- The new consoles consume more energy each year playing video or in standby mode than playing games.

- The Xbox One and PS4 consume two to three times more annual energy than the latest models of their predecessors, the Xbox 360 and PS3.

- While the new versions are more powerful, the two- to three-fold increase in energy-use is due to higher power demand in standby modes, and in the case of the Xbox One, more time switched on due to its TV-viewing mode. In that mode, the console is used in addition to the current set-top box to access cable or satellite TV, adding 72 watts to TV viewing. Do you really want a 72-watt remote control, when a traditional battery-powered remote draws less than 1 watt?

- The Xbox One draws less power than the PS4 to play games and video. However, the Xbox One consumes a lot more energy when not in use (connected standby mode).

- Nearly half of the Xbox One's annual energy is consumed in connected standby, when the console continuously draws more than 15 watts while waiting for the user to say "Xbox on," even in the middle of the night or when no one is home. If left unchanged and all Xbox 360 models are replaced by Xbox One consoles, this one feature will be responsible for $400 million in annual electricity bills and the equivalent annual output of a large, 750-megawatt power plant — and its associated pollution.

- Consoles have incorporated some good design practices, including better power scaling (drawing less power when doing less work) and well-implemented automatic power-down to a low-power state after an extended period of user inactivity.

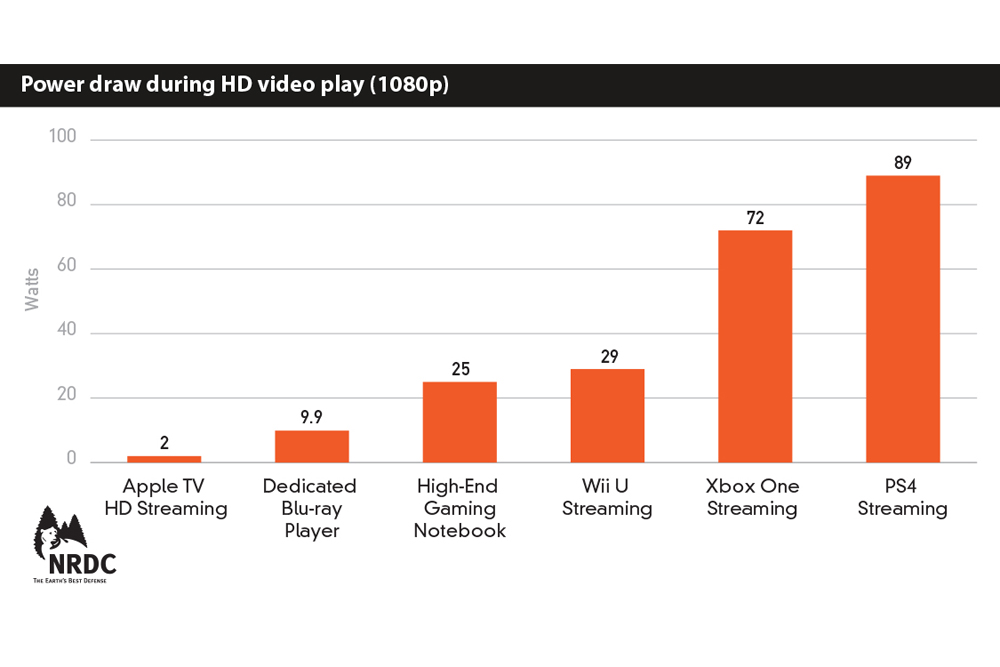

- The PS4 and Xbox One are very inefficient when playing movies from a streaming service, using 30 to 45 times more power to stream a movie than a dedicated video player, such as Apple TV, Google Chromecast or Amazon Fire TV.

Recommendations and priorities for energy savings

NRDC's detailed report includes several recommendations for how manufacturers can bring down the energy consumption of those consoles. The recommendations focus on giving users a clearer choice between higher and lower energy modes, reducing power in standby to levels similar to the Amazon Fire TV (which offers voice command for less than 3 watts) and reducing power when the processing needs are light, such as streaming video and TV mode.

NRDC estimates those improvements could save another 25 percent beyond natural semiconductor-efficiency trends. This would save American consumers $250 million annually in electricity bills and conserve enough electricity to power all the households in San Jose, the nation's 10th-largest city. Some of these recommendations only require settings or user interface changes; they can be implemented rapidly on new products and even on existing products via software updates.

Others require hardware design changes and will require more time, but work should start on them as soon as possible.

Game console manufacturers should leverage design best practices to reduce console energy consumption before too many units of the current models are sold and lock-in high-energy consumption for their owners for the next five years.

Author's Note: Testing was performed on launch units with system updates up to mid-April 2014. The effects of any system updates and hardware improvements released after that date are not reflected in the report. We just heard from Sony that new PS4s sold with the 1.70 software version released on April 30, 2014, reduce the default auto-power down time from two hours to one, and include a TV screen-dimming feature. We applaud Sony for these energy-saving improvements and encourage them to implement our other recommendations as soon as possible.

This Op-Ed was adapted from the NRDC post "The Latest-Generation Video Game Consoles: How Much Energy Do They Waste When You're Not Playing?" on the NRDC blog Switchboard. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.